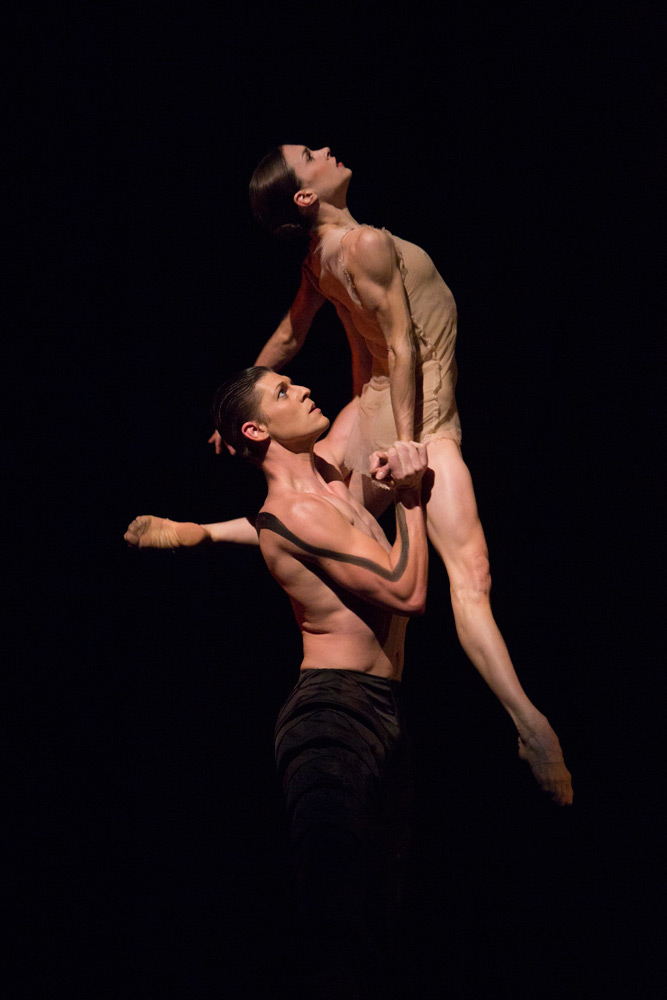

© Angela Sterling. (Click image for larger version)

Pacific Northwest Ballet

A Million Kisses to my Skin, The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude, Emergence

★★★✰✰

New York, City Center

27 February 2016

www.pnb.org

www.nycitycenter.org

Back to the Future

Having served up a night of Balanchine earlier in the week, Pacific Northwest provided New Yorkers with a dose of contemporary works over the weekend. Overall, the impression was of a company in top form, at ease in a variety of styles. The dancers have an easy-going, open demeanor that makes even the knottiest works look more appealing. Especially in the first piece of the evening, David Dawson’s A Million Kisses to My Skin, they radiated pleasure – the pleasure of moving together to a common impulse.

© Angela Sterling. (Click image for larger version)

Dawson, who is British, created A Million Kisses in 2000, for the Dutch National Ballet, where he was a dancer at the time. In a program note, he explains that the ballet was his farewell to classical dance. Set to Bach’s first piano concerto, in D minor (beautifully played by Allan Dameron and the PNB orchestra), it is a ballet that has swing. The movement style is an exaggerated version of Balanchinean neo-classicism, abounding in an exaggerated opposition of the shoulders and lower body, elongated arms, splayed fingers, and off-kilter poses on point. The nine dancers, clad in attractive blue leotards and bare legs (tights for the men), are in perpetual motion. The overall effect at this performance was one of almost ecstatic freedom, for both the men and the women. Lesley Rausch stood out for her strength and control; Leta Biasucci for the sharpness of her attack; Elle Macy for her soaring jumps. The men looked equally energized.

William Forsythe’s Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude, which followed, is a slightly earlier piece, from 1996, that also uses this vocabulary of embellished neoclassicism, pushed to a more heightened extreme. The ballet is a riff on the artifice of ballet, with elaborate bows and exaggeratedly grand port de bras meant to allude to the courtly manners of nineteenth century imperial dance. The tutus, flat discs in acid green, are part of the joke. The dancing here, set to the “allegro molto vivace” movement of Schubert’s ninth symphony, is fast and furious, even manic, leaving little room for dynamics or individuality. But the dancers certainly pulled it off.

© Angela Sterling. (Click image for larger version)

The most original piece on the program was by the much-in-demand Canadian choreographer Crystal Pite. Emergence, with its futuristic scenic designs by Jay Gower Taylor and striking, semi-reptilian costumes by Linda Chow, appears to be a meditation on the hive mind, the organization of individual elements into a larger collective. The dancers enter and exit via a hole at the rear of the stage; at times a bright, pulsating light shines out, momentarily blinding the audience. The music consists of an industrial, march like drone. As in Jerome Robbins’ The Cage, the dancers are imagined as creatures belonging to another species, with pincer-like hands, flickering legs and shoulders, arched and twisted backs.

Pite has a prodigious ability to transform single bodies, and whole groups, through her hyper detailed movement. She creates landscapes but also seems to get into dancers’ nervous systems. The results are like fabulous special effects – but to what end? One could imagine Emergence as part of a science fiction narrative or a video game; it would provide a fabulous human backdrop for an operatic spectacle. But on its own, it becomes a massive display of movement imagination without a guiding purpose, impressive but oddly empty.

© Angela Sterling. (Click image for larger version)

As a showcase for the company’s strengths, though, it works. With more than thirty dancers, Pite’s piece shows off the wealth of talent at Peter Boal’s disposal. New work is always a gamble, but good dancers are the lifeblood of a company.

You must be logged in to post a comment.