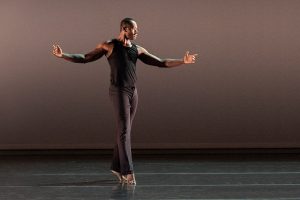

© David Kelly. (Click image for larger version)

Queensland Ballet

Lest We Forget: We who are left, Company B, In the Best Moments

★★★★✰

Brisbane, Queensland Performing Arts Centre

29 July 2016

www.queenslandballet.com.au

www.qpac.com.au

It was, I believe, Agnes de Mille who exhorted choreographers to aim to make an impact in the first 30 seconds of their works if they wanted to harness the interest of an audience. Choreographer Natalie Weir did exactly that in Queensland Ballet’s triple bill program, Lest We Forget, a program honouring the ANZAC soldiers of World War I. Weir’s work, We who are left, begins in darkness. One by one five male dancers are revealed, standing in individual pools of light. As we watch each man is joined by a woman and we can almost hear the women shouting ‘Don’t leave me’, ‘Stay’, ‘I love you’ as they throw themselves into the arms of their partners, cling to them, and reluctantly tear themselves away as their partners ready themselves to leave for the war zone. Instant emotional involvement is the only possible reaction. The five couples then lead us on a journey of parting, fighting, death, survival, longing, and memories of what was and what might have been.

© David Kelly. (Click image for larger version)

Choreographically the work is outstanding throughout. After the strongly emotional opening scene, the men engage in their war activities. At first their movements have a quality of military precision to them. But as this section proceeds they throw themselves around the stage in athletic leaps as they become more and more bound up in the process of war. Then, dramatically, an upstage screen lifts and four of the five men walk slowly backwards into the grey recesses that are revealed. The screen descends and just a single soldier, ‘The man who lived’ danced by Jack Lister, remains onstage. A lyrical pas de deux between Lina Kim and Camilo Ramos follows. It is a duet recalling memories of past times and is filled with Weir’s signature pas de deux style in which bodies tip, dive, twist and wrap around each other.

Perhaps the choreographic highlight, however, comes at the moment when Clare Morehen, ‘She who was left’, stands onstage with a pair of soldier’s boots in front of her. She dances around them, sometimes with sharp pique-style movements that suggest agony, sometimes with extended legs and stretched arms that suggest a range of other emotions. Then, surprisingly, she is joined by her man, Shane Wuerthner. They dance together but separately. Morehen stretches out to him but they never touch. They kiss but their lips never meet. He lies on the floor and she steps over him crisscrossing her way along the body. They are astonishing moments and present a totally different take on memory from what we saw from Kim and Ramos. Later, the other four women enter with pairs of boots and poignantly place them on the floor. But nothing can equal the dream-like moments we spend with Morehen and Wuerthner.

© David Kelly. (Click image for larger version)

The work is danced to selections from Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem Opus 66 and Weir has chosen largely from those sections of the score that include the spoken word in the form of poetry by Wilfred Owen. The score pounds relentlessly and adds a separate level of drama to the overall work. David Walters lighting design is spectacular throughout beginning with that striking downlighting in the opening moments, through to brooding lighting washing across the stage as the men find themselves in the act of war, and on to further pools of light highlighting the women as they survey the empty boots of those who did not return. Costumes by Noelene Hill are perfectly of the period and neutral in their colours.

We who are left has an innate simplicity – five couples, five sets of boots, basically a grey colour scheme. That’s about it on an obvious level. Yet it is masterful in its ability to communicate general thoughts about the effects of war, while at the same time conveying a sense of individuality. It is like a dagger in the heart with its theatricality, its choreographic sensibility, and its dramatic power. It is nothing less than a knockout.

© David Kelly. (Click image for larger version)

The other two works on the program were Company B, Paul Taylor’s classic made in 1991 to songs by the Andrews sisters, and Ma Cong’s newly commissioned In the best moments. Company B was nicely staged for Queensland Ballet by Richard Chen See and the dancers appear to have been strongly coached by him to understand where Taylor, and Company B in particular, fit into the history of modern dance. So, while we might have been tempted to look at the choreography and think it is somewhat outmoded in 2016, in fact the work looked very fresh. It was joyously danced and the reference to war, through the constant leitmotif of men falling to the ground in the middle of the dancing, remained clearly defined. I especially admired Joel Woellner’s vigorous Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy (of Company B), and There will never be another you danced with a wonderful sense of attachment to each other by Vanessa Morelli and Victor Estevez.

© David Kelly. (Click image for larger version)

Ma Cong’s In the best moments, danced to Philip Glass’ The Hours Suite, contained some lovely groupings and stage patterns throughout its three movements. Consisting largely of duets for seven couples it was very easy on the eye. It was a nice opener, although I was surprised later to read a program note that said of the choreographer’s intention ‘War can intensify feelings of love, commitment and passion.’ It wasn’t an intense piece.

Under the directorship of Li Cunxin Queensland Ballet has gone from strength to strength. The repertoire continues to be exciting and courageous and the dancers are looking better and better every time I see them. The company is putting itself on the line and is becoming a challenge to other Australian companies. What could be better for the future of dance?

You must be logged in to post a comment.