© Paula Court. (Click image for larger version)

Nick Mauss

Nick Mauss: Transmissions – exhibition

New York, Whitney Museum of American Art

Seen on 26 March – Runs through 14 May 2-18

www.303gallery.com/artists/nick-mauss

whitney.org/Exhibitions/NickMauss

whitney.org

There’s no question that Nick Mauss’s “Transmissions” exhibit, currently running at the Whitney, is a pleasure to walk through. This is true not only for the ballet-lover, who will recognize a good number of the images and works of art on display, but also for the casual visitor, who might never have given much thought to ballet, or its place in New York’s modern-art scene during the first half of the twentieth century. But is it really a well-thought out, illuminating exhibition? Of that I’m not so sure.

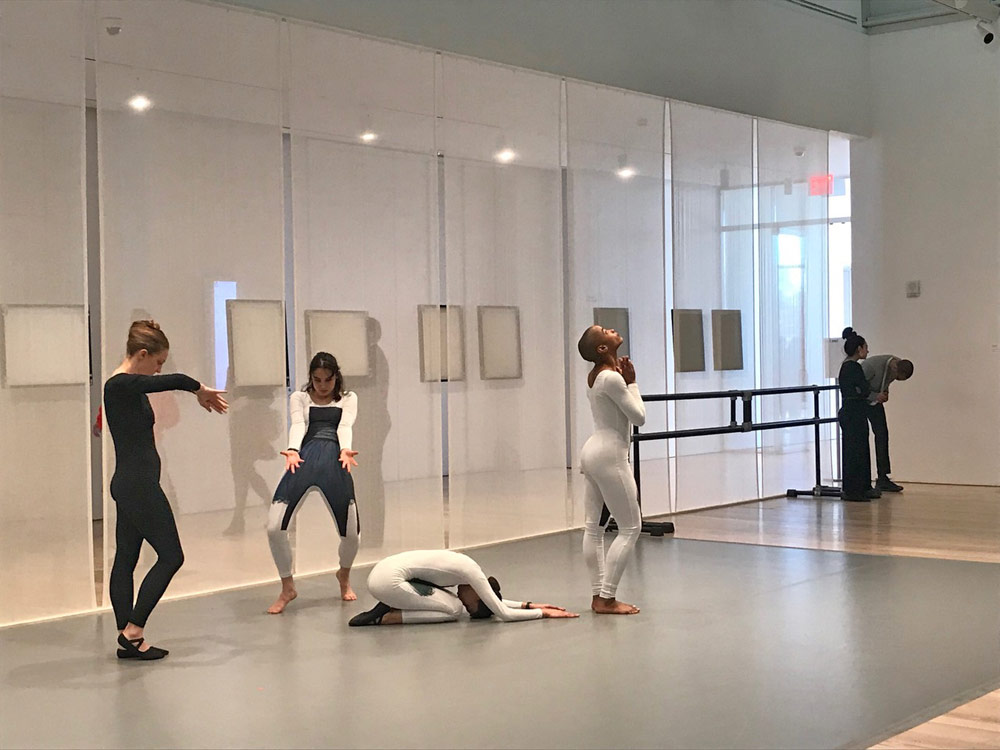

Nick Mauss, 38, is a painter and sculptor who has more recently taken to curating shows that combine his own work and items he turns up through research. His current exhibit is the result of a prolonged exploration of modernist ballet in New York and its relation to the artistic avant-garde between the 30’s and 50’s. The items come from the New York Library for Performing Arts, the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, and the Whitney’s own collection. They include photographs, costumes, paintings, sculptures, video, and, for several hours a day, low-key performances by small groups of dancers on a platform at one side of the large 8th-floor gallery. The dancers perform in silence, or rather, accompanied by the ambient noises of the exhibit itself.

photo © Marina Harss. (Click image for larger version)

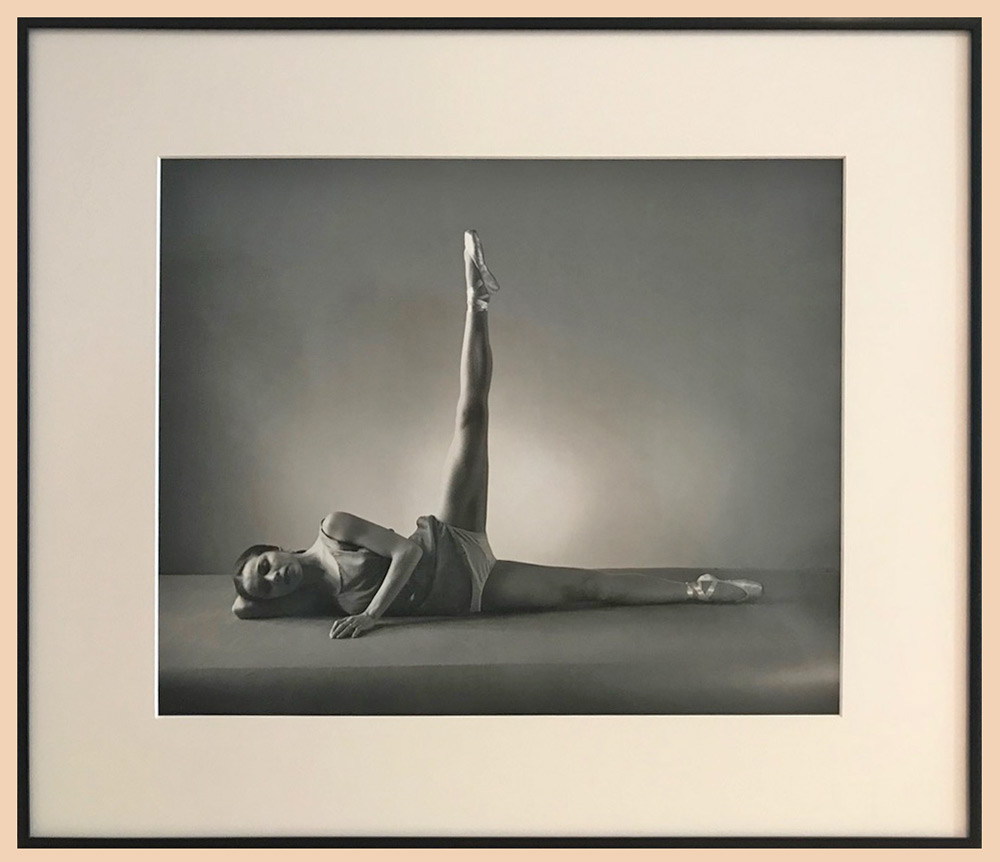

There is also a complementary angle, as explained in the wall text; the exhibit explores homosexual eroticism through the prism of modernism and ballet, particularly as seen in the work of George Platt Lynes, a photographer known both for his studio portraits of dancers, but also for his male nudes, which included images of dancers photographed with an distinctly sensual eye. Along one semi-translucent wall in the gallery, one can see: a photo of three black performers from Virgil Thomson’s “Four Saints in Three Acts,” reclining languidly and nude as the British choreographer Frederick Ashton gazes upon them with what now reads as patronizing fondness; a frontal nude of Nicholas Magallanes, of New York City Ballet; an image of one of George Balanchine’s favorite dancers, Diana Adams, in costume for the ballet “La Valse”; his third wife, Maria Tallchief, another City Ballet star, extending a leg to the side as she lies on the floor, in a ballet tunic; and a picture of a man rolled up in a ball so that he offers his rear end to the viewer. It’s an odd juxtaposition, which I suppose is part of the point. Closely-related worlds rub shoulders along a gallery wall as they did in the overlapping circles around the New York Ballet and the New York visual art scene.

photo © Marina Harss. (Click image for larger version)

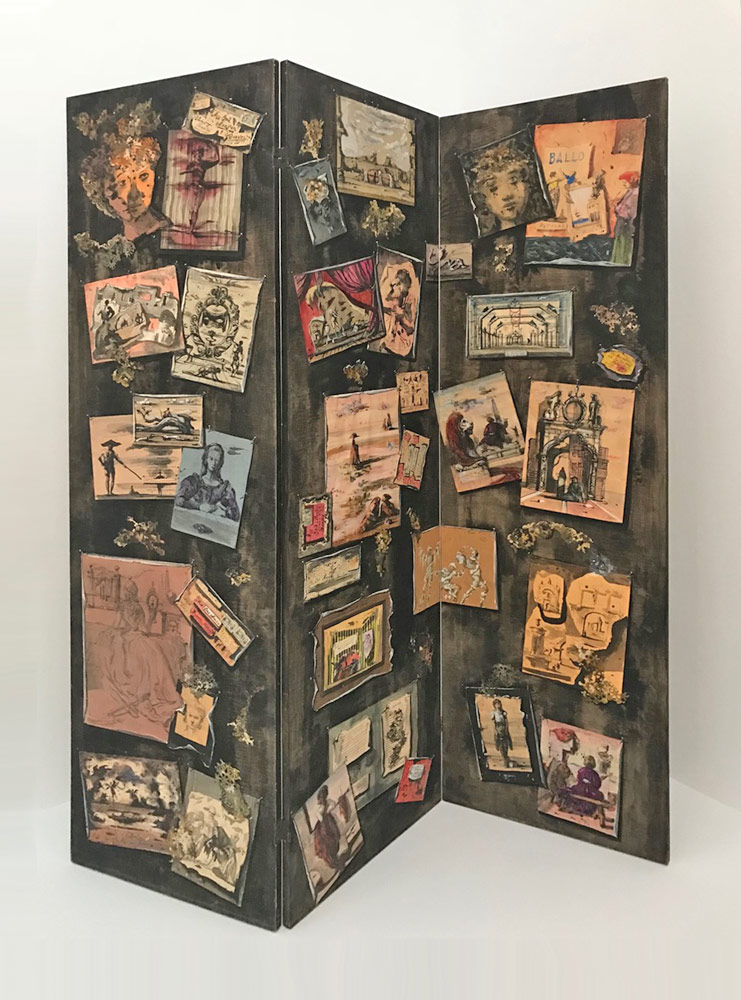

Much of the exhibit could be described this way. The organizing principle is that of juxtaposition. A striking three-panel screen covered in watercolors by the Rococo surrealist, and theatre designer, Eugene Berman stands in a corner, near a sketch of Loie Fuller’s aqueous eyes, by an unknown artist, and a few feet away from a psychedelic, almost kitschy depiction of the human circulatory system by the Russian-born surrealist Pavel Tchelitchew. (Tchelitchew, who had mystical tendencies, was a friend of both Gertrude Stein and the upper-class intellectual siblings the Sitwells.)

photo © Marina Harss. (Click image for larger version)

Behind a partition, a small rectangular glass box contains a beautifully-rendered neoclassical design for George Balanchine’s 1941 ballet “Concerto Barocco,” also by Berman. Balanchine’s tastes simplified over time, and the ballet is now performed without sets or elaborate costumes, but Berman’s jewel-like set makes you regret the change. Along with the Tallchief portrait, it’s the most beautiful item in the exhibit.

photo © Marina Harss. (Click image for larger version)

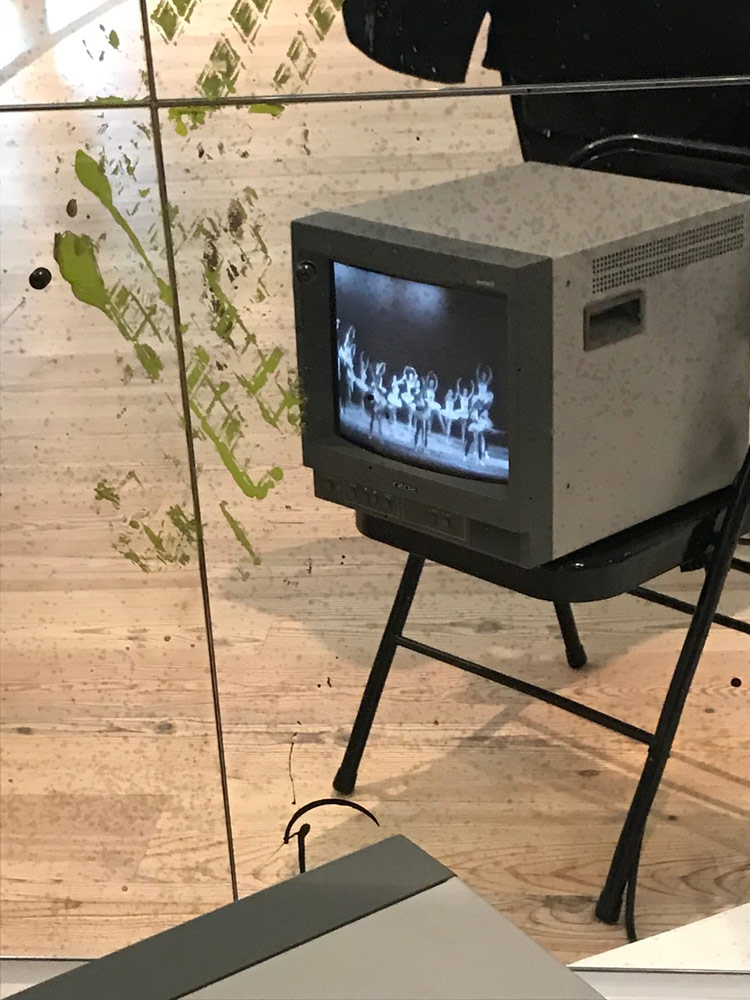

In another corner, Mauss has created an installation that includes a wall of painted glass (of his own creation) and a small television playing videos of Balanchine working in the studio with his dancers. Spend some time watching Balanchine work and you’ll understand why his choreography is so uncannily musical; he “conducts” the dancers as if they were instruments in an orchestra. A pair of bulbous figures by Elie Nadelman stand guard nearby. Nadelman was championed by Lincoln Kirstein, the art critic and patron who made it possible for Balanchine to turn New York City Ballet into a successful concern after decamping from Europe. To this day, two giant Nadelman statues loom over the promenade at the New York State Theater (now the Koch), home of New York City Ballet. Everything is interrelated.

photo © Marina Harss. (Click image for larger version)

But how does it all fit together? And what does Mauss’s assemblage tell us?

Not very much, unfortunately. Like the dancers in the exhibit, who quietly do their thing on one side of the gallery space – pacing, pointing their toes, bourréeing, interlinking arms, forming circles and friezes – the exhibit never quite becomes more than the sum of its individually-intriguing parts. What is Mauss’s insight into this little world he has reconstructed so elegantly? How do its elements complement each other? What do they reveal about ballet, or modernism, or erotic photography, or his own art? After spending a couple of hours among these tidy fragments, it wasn’t at all clear. For me, at least, the exhibit remained an attractive, personalized assortment, but without much to say.

Apart from the live dancers and Nik Mauss’s own wall drawings, every element in this charming show is connected to Lincoln Kirstein–as donor, friend of the artist, promoter of the art, cofounder of the home institution, erstwhile owner of the object, liaison, lover, whatever, although the point is never explicitly made. Kirstein himself is represented by a figurative sculpture and some references, but the lines between them and everything else are very low-key, and the threads tying up the whole are so unstressed that this visitor to the show had to think about them a long time, taking an inventory of what has been excluded, to discover, finally, the Minotaur at the center of the maze. Did the curator intend the show to operate this way? Did he further intend to suggest that he and the dancers of his own era have something to learn from the idiosyncratic yet fascinating way that ballet and homosexuality related in Lincoln Kirstein’s brain? Or is the point that Lincoln Kirstein’s brain is the brain of the 21st-century ballet audience, which embraces disconnection as a virtue and needs no guidance in making connections? Surely, if this exhibition had been on view ten years ago, in conjunction with the release of Martin Duberman’s biography “The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein,” and the book had been on sale in the museum shop, then its enigmas might have immediately clicked open. As for the general public, they may find the show more delightful and mysterious–a charming collection of curios, as Marina suggests it can be, absent any intellectual pressure–if they aren’t moved to ruminate on what its connections potentially are.

I’m glad you found the glue, Mindy! Lincoln Kirstein really was the beginning and end of everything in NY at that time.