© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

CCN Ballet de Lorraine and Compagnie Amala Dianor

as part of Dance Umbrella and FranceDance UK

The Future Bursts In: Somewhere in the Middle of Infinity, For Four Walls, Sounddance

★★★★✰

London, Linbury Theatre

24, 26 October 2019

Gallery of pictures by Foteini Christofilopoulou

ballet-de-lorraine.eu

amaladianor.com

www.roh.org.uk

www.danceumbrella.co.uk

The title of the latest triple bill in the ROH Linbury Theatre is taken from The Observer’s dance critic’s review of the Merce Cunningham Company’s arrival in Britain in 1964. Nigel Gosling (writing as Alexander Bland) acclaimed Cunningham as the creator of an art of the future, while ‘talking in the language of today’.

Emma Gladstone, director of Dance Umbrella, wondered whether Cunningham’s creations would now be considered classics, a hundred years after his birth. She asked the Ballet de Lorraine, who perform a large number of Cunningham works, to bring his 1975 Sounddance to the Umbrella festival, along with a new tribute piece, For Four Walls, by its artistic director, Petter Jacobsson, and Thomas Caley, who was a member of Cunningham’s company.

Since Dance Umbrella’s remit includes introducing new artists to Britain, Gladstone welcomed Amala Dianor’s company from Angers, which is also part of FranceDance UK’s festival of contemporary dance. The choice of the Linbury Theatre for this triple bill enables the Royal Opera House to attract audiences who aren’t solely interested in ballet.

Dianor’s dance language, in Somewhere in the Middle of Infinity, is a combination of hip-hop, contemporary moves and African influences. Dianor (who is originally from Senegal) and two companions, Ladji Koné (from Burkina Faso) and Pansum Kim (from South Korea) set out on a journey together. They are not migrants but explorers, testing their own boundaries and their allegiances in a space ‘somewhere in the middle of infinity’.

© Valérie Frossard. (Click image for larger version)

They start by agreeing to remove their shoes and to assume a combined pose that resembles a tree. Upside-down Dianor forms the trunk, with the other two curving their arms as the branches. They will return to this reference point several times before the (temporary) conclusion of their journey.

Their dance is a series of negotiations. They look at each other questioningly, establish a sequence of moves, and try them out with elaborations – reversing or speeding up as they select sections of Awir Leon’s sound score via an electronic tablet. Their base is a rhythmic pacing, knees bent, body kept low, swaying from side to side. They are mesmerising, compelling. Each one breaks away to make his own statement: Dianor performs a slo-mo breakdance, Koné reaches out and Pansum Kim writhes sinuously, while the other two smile at his showing-off. He tries to engage them in disco jiving, but they demur.

They renegotiate. Shoes are put back on for a wild jumping sequence, then linked pacing, travelling together with an arm on each other’s shoulder. Whether they pound their feet to African percussion or perform hip-hop athletics, all three are elegant performers. After 40 minutes, they return to their tree position and lie down, as though dreaming, in a golden light. Up they get, shifting their weight from foot to foot, their journey never-ending.

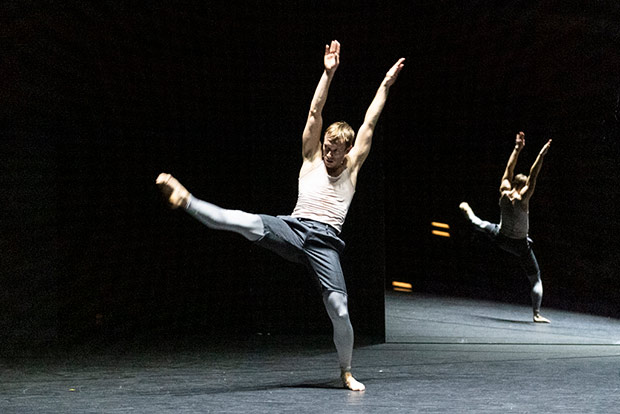

© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

They made the neutral space of the Linbury, the stage covered in white flooring, seem magical. After an interval, it was transformed into a disconcerting hall of mirrors for Caley and Jacobsson’s For Four Walls. The title refers to John Cage’s score, Four Walls, for a 1944 dance by Cunningham, performed only once and virtually forgotten. This tribute is not an attempt at reconstruction but a reflection on Cage and Cunningham’s shared history and their influence on today’s dancers and dance-makers.

The opening image is stunning. A line-up of youngsters dressed in casual sports clothes is multiplied by angled panels so that we see them from behind and in front without being able to tell how many there are. The pianist, Vanessa Wagner, appears at first to be on a different plane – she isn’t – as she plays Cage’s early composition, which uses only the white notes of the piano. The score sounds remarkably like Erik Satie’s meditative Gymnopédies, used by Frederick Ashton for his Monotones trios.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

The 23 dancers, countable only when they take their bows at the end, do respond to music cues, unlike Cunningham’s former company members. They often look like teams of ball players, observing rules and strategies we can’t hope to follow. The stage picture fragments with flying bodies, each pursuing a different trajectory. Disorder appears to reign, though no one bumps into anyone else. Fix on just one dancer, say Céline Verbier, Willem-Jan Sas or Nathan Gracia, and their solo roles emerge, amplified by the mirrored panels.

The structure of the piece becomes clearer on a second viewing, as the music changes from single notes to crashing chords. There’s an outbreak of partnering, with dancers hurtling into each other’s arms, regardless of sex or weight. At one point, the pianist turns round, watches the leaping figures and exits the stage. The cast withdraws to the edges of the panels, chanting in unison. When they reoccupy the stage, it’s one of many false endings before the last dancer leaves and the pianist finally closes the lid on the keys.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

The energetic busyness of For Four Walls somewhat undermined the impact of Cunningham’s 1975 Sounddance, which followed after a short break. The mirrored panels, deftly removed by stagehands, were replaced by a draped and knotted curtain suspended from a horizontal pole. The folds and twists of fabric, designed by Mark Lancaster, are visual echoes of the interwoven choreography for ten dancers. Some, with impressive stamina, had already performed in For Four Walls.

Out of a slit in the curtain bursts a soloist – Willem-Jan Sas on the first night, in the role Cunningham made for himself. He is soon joined by others, who form a square or split into pairs and trios. They are constantly in touch with each other, linking arms or gripping wrists. Women are raised and suspended like bridges, swung between men like gymnasts or children. Holding hands, two groups form a circle, trapping a dancer in their midst. Another grouping resembles a fountain, with a man surrounded by women, hands flutttering.

© Laurent Philuppe. (Click image for larger version)

Suddenly, the patterns disperse as the dancers slice across the stage in stag leaps. David Tudor’s sound score of sonic blasts crackles from speakers, realised live by Etienne Caillet. The build-up of sound and speed is electric as the dancers are buffeted around the stage until one by one, they are sucked back into the slit in the curtain – a black hole swallowing them up. The Cunningham soloist is the last to go.

It’s all over in just 17 minutes, the most succinct and satisfying work in the triple bill. Rambert Dance Company used to perform Sounddance on tour back in 2012. Let’s hope its choreography is included in the company’s Cunningham Event at Sadler’s Wells in November. It is indeed a modern dance classic that deserves to be widely seen as often as possible.

You must be logged in to post a comment.