© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

Opus 19/The Dreamer, Amaria, Russian Seasons

★★★✰✰

New York, David H. Koch Theater

21 September 2021

www.nycballet.com

davidhkochtheater.com

Moving On

This fall season at New York City Ballet is one of returns, but also one of farewells, including the departure of Maria Kowroski on October 17, after twenty-seven years with the company. In this first week, she is being featured in two pas de deux, Christopher Wheeldon’s After the Rain and a new piece made for her by the Italian choreographer Mauro Bigonzetti.

The latter, entitled Amaria – which means “for Maria,” and is also an amalgamation of her and her partner’s names – was the centerpiece of the company’s second program, on September 22. Bigonzetti has featured Kowroski in all his works for New York City Ballet, and the two have developed a close rapport. The pas de deux, created via Zoom, is a gift to her. Bigonzetti clearly relishes her movement quality, her melancholy aura, and her impossibly pliant and long limbs. I wish I liked the piece more. Set to two beautiful Scarlatti keyboard sonatas played onstage by Craig Baldwin, it consists of a short suite of solos and convoluted pas de deux in which Kowroski bends and loops her frame in extreme ways, holds a leg up to her face, wraps it around her partner (Amar Ramasar) like a long tail. Ramasar partners her with gentle care, staying mostly in the shadows.

© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

Kowroski’s choice of Ramasar to partner her in this creation made in her honor is also a gesture of friendship and, perhaps, forgiveness. Ramasar is one of the dancers who was removed from the company after a scandal involving sexually-explicit texts, and later, after mediation, reinstated. On occasion, his performances have been picketed. Maybe it is a sign that the pandemic has helped to heal wounds. He retires in May.

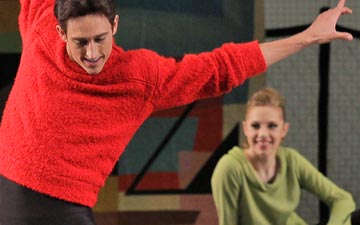

The Bigonzetti was sandwiched between Jerome Robbins’s 1979 Opus 19/The Dreamer and Ratmansky’s 2006 Russian Seasons. Opus 19, originally made for Baryshnikov, is not one of Robbins’ great works. It begins promisingly, with a meditative solo, but soon meanders into ersatz angst. It also fails to grasp the Russian tonalities of its Prokoviev score (the first violin concerto). But Gonzalo García has always glowed in the role of the dreamer, staring out in the darkness, reaching for something beyond his grasp. García is also retiring soon, in February. It will be a loss. His partner, a shadow figure who appears and disappears, weaving through the ensemble, was danced by Tiler Peck, with her amazing ease. Peck tried to make sense of the role by applying dramatic accents here and there; but nothing can really fix the vagueness that plagues this flawed ballet.

© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

Russian Seasons, Alexei Ratmansky’s first work for the company, and the one that alerted the New York ballet world to the fact that there was an important new choreographer in our midst, was the highlight of the evening. It still feels amazingly fresh, even surprising. I noticed several details last night that I had never seen before: a dancer whispering into the ear of another, another dancer whistling in the corner. The ballet, set to a song cycle by the Russian composer Leonid Desyatnikov, evokes a world steeped in folk imagery: games, barnyard sounds, dreams, death, a crucifixion. It creates a little world, full of suffering and joy. But it is also full of formal felicities, like the way the dancers’ phrases overlap onstage, creating a sense of polyphony, variety, counterpoint.

Georgina Pazcoguin dug into the role of the woman in red, first danced by Sofiane Sylve, a portrait of fury, fear, helplessness. Pazcoguin’s body seemed riven by conflicting impulses. She also used her face, something this company is not known for, to magnify the drama. Adrian Danchig-Waring, stylish and stylized, stretched every position to the fullest, turning his body into a series of oblique angles. Kennard Henson leapt high and far, like a young man frolicking in the fields.

© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

Fifteen years after its creation, Russian Seasons is still pushing the dancers, and still revealing new aspects of their personalities. It evolves with each new cast. It’s a keeper.

You must be logged in to post a comment.