© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

Boston Ballet

Edge of Vision: Bach Cello Suites, Eventide, Celts

Boston, Opera House

30 April, 1 May, 3 May (mat), 2015

bostonballet.org

For its penultimate program of the season, titled Edge of Vision (don’t ask), Boston Ballet offered three ballets which were all company commissions spanning almost two decades: Celts by Lila York (1996), Eventide by Helen Pickett (2008), and Bach Cello Suites by the company’s resident choreographer Jorma Elo which had its world premiere in this production. The evening was full of surprises, not least that two of the three choreographers were women and that Jorma Elo broke radically new ground in his Bach Cello Suites.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

I recall enjoying Celts at its premiere in 1996 and find it as much of a crowd pleaser as before. Although based on Irish step-dancing, a form of entertainment I find only marginally more pleasing than root canal treatment, York transfigures her source material, working inventive changes throughout. At first, we see the usual clodhopper clog movement, but immediately the dancers begin weaving in and out of a variety of engaging patterns. The plangent music, by Paddy Moloney, Bill Ruyle, and “traditional”, nicely renders the primeval mood. (By 300 BCE the Celts covered all of Great Britain, most of continental Europe, and even parts of Anatolia.) A chorus of 13 loose-haired women sometimes appeared as Druid maidens and other times Cretan naiads. Halfway though, six men in red kilts engaged in lethal Spartan combat, grappling and colliding until a single man stood triumphant over the bodies of his defeated foes.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

On opening night, Lasha Khozashvili was a dynamic leader of the Spartans and Jeffrey Cirio was a miracle of speed and precision as the black-clad MC of the proceedings. The other principals – Lia Cirio, Dusty Button and Eris Nezha – also merited high praise.

Helen Pickett’s Eventide, which the company premiered only seven years ago and which has since been twice revised, is now set to music by Philip Glass, Ravi Shankar, and Jan Garbarek. In the program notes, Pickett says that eventide , meaning evening, “gathers us into the cyclical energy of transition, that ephemeral space between where life’s entirety seems graspable.” That’s the first problem. The second is that the final half of the piece is set to Glass music so relentlessly monotonous that I felt like the victim of an esoteric Chinese torture. Pickett doesn’t lack talent or intelligence, but she suffers from a plethora of ideas and the compulsion to get them all in. The notion that less could ever be more is wholly alien to her. So we have a good deal of classical ballet tweaked modern, plus a bit of jitterbugging, then some spastic angularity a la William Forsythe (with whom Pickett danced for 11 years), then several couples each with its own center of attention so you have no idea where to look. When the punishing music finally ended, it was like being released from prison.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

Kathleen Breen Combes and Sabi Varga were a splendid couple opening night, exuding elegance and calm authority, and their peers were also commendable: Erica Cornejo, Seo Hye Han, Whitney Jensen, Paulo Arrais, John Lam, and Irlan Silva. Would that their talents had been put to better use. (The audience loved it, by the way.)

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

Jorma Elo’s Bach Cello Suites is in every way a magnificent accomplishment, and an amazing one coming from a man whose past choreography has often portrayed dancers as demented praying mantises or spastic chickens in heat. Now the movement is liquid and lyrical, the emotions spacious and large, and the mood is of a poignant intimacy between men and women that is often heart-wrenching.

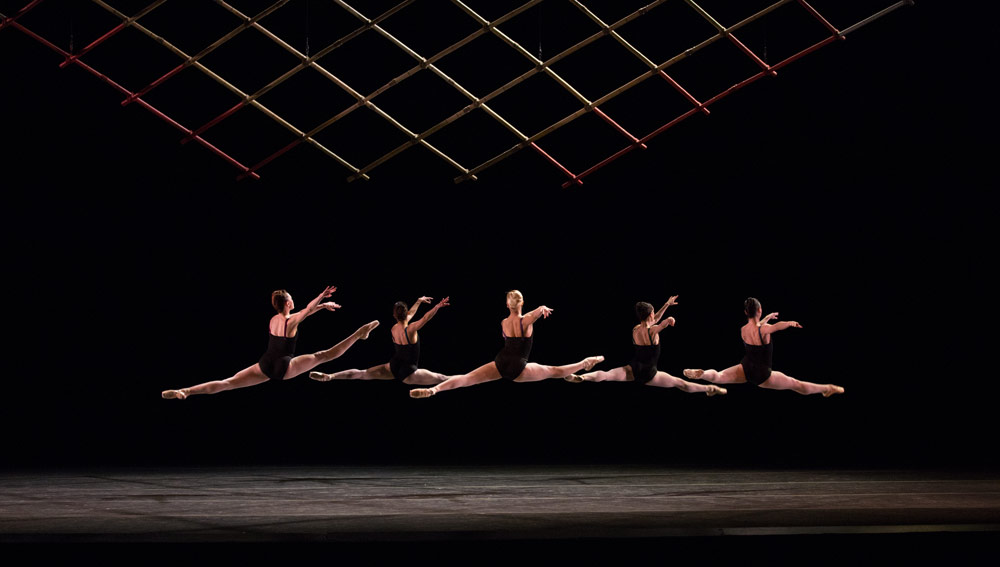

The dance begins with the brilliant Sergey Antonov playing the prelude to the first of Bach’s Suites for Unaccompanied Cello. (Antonov won the gold medal at the 2007 International Tchaikovsky Competition, one of the youngest winners in its history.) Hanging from the ceiling we see a huge white lattice construction by Artistic Director Mikko Nissinen (another surprise), which shifts from scene to scene. A couple slowly strolls on stage, tenderly embracing. They seem to be exploring the boundaries of their intimacy in movements of exquisite delicacy. They are joined by other couples, the women in black leotards and the men in black tights and T-shirts, who meld in and out of larger configurations, always gently and seamlessly.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

The choreography also provides indelible images, as when a man with bent legs positions a woman on his thighs like the prow of a ship, or departing partners abruptly turn and look back at each other, or five men turn their backs to the audience and raise their arms in a victory sign. (This V sign appears throughout, suggesting emotions of awe, victory, celebration.) Five dancers collapse in a row like mechanized dominoes. One passage ends with three women kneeling in profile and their men with raised arms: an Egyptian frieze of divinities. The lifts and leaps and turns are miracles of beauty, and the minimal set and costumes plus the unaccompanied cello create a sense of great simplicity and purity. It’s also been a long time since I saw a piece of choreography so integrally related to its score. Balanchine’s words kept coming to mind: “Dancing is music made visible.”

Halfway though, a figure in loose black clothes appears and maneuvers the dancers into position, a choreographic Demiurge or a Dr Coppelia conjuring his dreams into reality. (Opening night this role was performed by Jorma Elo, Erica Cornejo thereafter.) At the end, this figure guides the final dancer into darkness as we hear the final note of the Bach.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

The dancing I saw at all three performances of this production was superlative. Sabi Varga, a Soloist, partnered several of the best women in the company and was always a stand-out, considerably better than some of the male Principals. As always, Kathleen Breen Combes left me speechless with admiration and Jeffrey Cirio astounded me with his versatility. I’d never previously noted Petra Conti, now ending her first season in the company, and was delighted to discover a dancer of such grace and charm. Dusty Button, with her Platonic Ideal of a Balanchine body; Whitney Jensen, who makes me think “Yes, this is how it should be done”; Erica Cornejo with her vital sensuality; Misa Kuranaga with her quicksilver delivery; the lovely Soloist Seo Hye Han, who holds her own with the other female Principles; and Paulo Arrais, happily back with the company after a year’s absence – these are all amazing dancers. This company’s cup runneth over.

As for the three ballets on view, Celts will continue to delight for a good long while, Eventide will end as a footnote in the dance history of our time, and Elo’s Bach Cello Suites will endure for the ages.

You must be logged in to post a comment.