Royal Ballet

Polyphonia, Sweet Violets, Carbon Life

London, Royal Opera House

5 April 2012

Gallery of 32 pictures

by Dave Morgan

www.roh.org.uk

This much-anticipated triple bill with two world premieres featured works by British choreographers closely associated with the Royal Ballet: all three – Christopher Wheeldon, Wayne McGregor and the youngest, Liam Scarlett – have had commissions from other companies, so this promised to be a programme of international interest. Alas, Wheeldon’s Polyphonia, created for New York City Ballet in 2001, outshone both new works and his later commissions from the Royal Ballet.

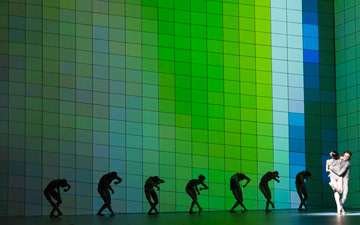

In Polyphonia the eight dancers treat Ligeti’s piano studies and each other with courtesy and wit. The women appear weightless, skimming the stage like insects skittering on water, or floating in their partner’s arms. Leanne Benjamin is sensational in her two pas de deux with Nehemiah Kish, her tiny body infinitely flexible without ever seeming contorted. Beatrix Stix-Brunell drifts beatifically on pointe in her solo, sustaining the most elegant battements lents. Alexander Campbell and Dawid Trzensimiech vie for the fastest footwork and the quirkiest girls, Yuhui Choe and Itziar Mendizabal. Wheeldon can draw on an extensive classical ballet vocabulary while inventing his own variations; his dancers remain tender human beings even while describing improbable circles over and under their partner’s body – as Benjamin does with Kish.

In Carbon Life, Wayne McGregor’s cast resemble Cirque du Soleil acrobats or dance students imitating Michael Clark videos from the 1980s. For a change, there is no programme note alluding to a creative concept. Instead, rock and pop musicians form an eclectic onstage group, singing of love. A massed band of unisex dancers in minimal outfits struts in simple tendus while Alison Mosshart asks ‘Is anyone out there?’ So far, so banal. Bits and pieces of costume (designed by Gareth Pugh) are added to nudist suits throughout the show: black trunks, tutus, shin guards, thigh-high boots, pointy headgear. A carbonizing process, presumably.

If you watched the ‘Royal Ballet Live’ streaming online, you would have seen McGregor rehearsing duets in detail, revealing that they were all about sexual attraction, even obsession. Seen from a distance, however, the couplings look much like McGregor’s familiar writhings, ripplings, splayings and manhandlings, the only difference being that they’re sealed with kisses. Since there’s no coded structure to his choreography, unlike Wheeldon’s, it’s hard to get a grip on whatever he’s trying to convey. Are we being shown gradations of love? Dancers and their relationships to each other and the songs are unrecognisable. The music, to my ears, is unmemorable. The overall effect is as modishly bland as a trade show to pop music – one designed to attract an inexperienced audience.

Sweet Violets is Scarlett’s sincere attempt at a narrative ballet, with its attendant problems. He faced the same difficulties Kenneth MacMillan confronted in Mayerling: a gallery of ‘historical’ named characters, some with mental or physical conditions ballet can’t specify; information imparted on sheets of paper spectators can’t read; complexities of plot that need to be mugged up in advance. The only way round the requirement for audience members to pay attention to programme notes is to reduce a story to such basic elements, as Boris Eifman does in his ballet-dramas, that all subleties are abandoned. Personally, I’d rather make an effort than be bludgeoned into submission.

I hope Sweet Violets isn’t written off as too muddled to revive in future seasons. It deserves to be seen several times, with foreknowledge of its morbid story. Scarlett is trying to suggest the disturbed mind of an artist, Walter Sickert, whose paintings reveal his fascination with violence and squalor. Sickert frequented the same sort of seedy milieux as Toulouse-Lautrec and Degas but his London lacks the dubious glamour of Paris. Instead of the Moulin Rouge or the Paris Opera, Sickert lurked backstage at the Old Bedford Music Hall on Camden High Street. The claustrophobia of his north London settings has been captured in John Macfarlane’s sets, in which Sickert’s studio is only slightly less slummy than his subjects’ bedrooms.

Here’s what you need to know. Sickert apparently had a deal with royalty, in which he was supposed to look after Prince Eddy, Queen Victoria’s libertine grandson. The arrangement went wrong, in that Eddy fell for a working girl, Annie Crook, one of Sickert’s models; he may have married her in secret and had an illegitimate child. Annie had to be removed as a threat to the establishment, as did her accomplice, Mary-Jane Kelly. Sickert had an artist friend, Robert Wood, who was suspected of murdering a prostitute in Camden Town. He appears in one of the paintings, seated on a bed next to a naked woman. Sickert was obsessed with the Jack Ripper murders and believed he knew the identity of the notorious killer. The American crime writer Patricia Cornwell has identified Sickert as the Ripper, without forensic proof.

In Scarlett’s account, Johan Kobborg is the first-cast Sickert, combining creepiness with Victorian respectability. He dismisses Alina Cojocaru as his assistant, Mary-Jane Kelly, for informing on Eddy’s affair with Annie Crook (Laura Morera). Then he suffers remorse on discovering she’s reduced to selling herself outside the music hall. Even worse, she obliges him to witness Annie’s downfall, mad or syphilitic in an asylum. Sickert resorts to extreme measures to rid himself of his guilt. Kobborg, a fine actor, manages to be repressed and psychotic, haunted by his sinister alter-ego, Jack – Steven McRae, a mad-eyed shadow of death.

Meanwhile, Thiago Soares as Robert Wood has murdered Leanne Cope, who reappears to him as a reproachful ghost. While the downtrodden low-life girls are too similarly costumed in grey, Tamara Rojo, Sickert’s top model, undresses provocatively in red. She poses with Soares, which cannot bode well for her. A dancing girl in a blood-red tutu (Emma Maguire) must be doomed, as are her companions, touched by slimy Jack. Their variety act ballet, after which they’re joined by stage-door johnnies, offers an all-too-brief respite from gloom and disaster. Lit by David Finn, the ballet girls in their colour-saturated tutus closely resemble Degas’ paintings and pastels, as his eyesight faded.

Scarlett has had to find ways of working with and against his choice of music: Rachmaninoff’s Trio élégiaque, written in grief at Tchaikovsky’s death. Sometimes music and action coincide brilliantly, as in the angry opening duet, with Wood washing his hands to tinkling notes after the first murder; or dying Annie rapturously fantasising the return of Eddy. Backstage at the music hall, however, the revelry is constrained by Rachmaninoff’s changes of mood and tempi. The choreography throughout is musically and dramatically expressive, never tortuous in spite of its subject matter.

There are too many changes of scenery and too many characters as Scarlett attempts to evoke Sickert’s canvases and combine high and low intrigue, real or imagined. (Christopher Saunders puts in enigmatic appearances as the Victorian Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, while phantom McCrae skulks conspicuously in corners).The first-night audience seemed baffled, to judge from nervous clapping during scene changes. Scarlett rallied more generous applause when he took confident bows in front of his cast, hand modestly on heart. And what a starry cast of principals and soloists, fully involved in their characters’ horrid fates. Sweet Violets, though over-ambitious, is the best stab at a psychologically complex narrative ballet the company has commissioned for years.

The second song in Wayne McGregor’s piece, was sung by Alison Mosshart, not Boy George (who only came on towards the end)

Duh – now corrected. With apologies to all concerned. And thanks for saying.

Sweet Violets over ambitious? Well not for me.I think its one of the best things to be brought into the Royal Ballet rep for a long time and Liam surely has a wonderful future as a choreographer.I love everything about Sweet Violets from the stage sets to the music to the choreography and it was danced superbly by the entire cast on both occasions I have seen it.If this is an example of what Liam can do with a psychological narrative ballet I sincerely hope it won’t be his last.

Jann, I’m not sure reductionism in extremis was needed by Scarlett for Sweet Violets to be rescued. Handel achieved a pretty high level of complex psychology in his pared-down opera plots, by the richness of musical language he deployed. I deliberately didn’t mug up the programme notes, so watched with initially high interest stimulated in what I interpreted as the following scenario. An artist (Kobborg) is aware of his dark imaginings and hates himself. Among his friends are a sane and loving couple (Bonelli, Morera), from whom he realises he is alienated by his own nature. A rich (diabolical agent) patron (Saunders) demands a picture from him in his characteristic sinister vein, and a ghoulish spirit (the devil, McRae) represents the evil inside him, his alter ego, that tips the artist out of reality and into commitment to his latest ghastly fantasy. He searches among his acquaintances for those who will embody his imaginings. He needs to transfer his guilt onto another man (Soares) to exculpate himself. And he needs the girl – his assistant (Cojocaru) can’t go there and tries in vain to prevent him, but his model (Rojo) understands, and like Marie Vetsera in Mayerling will go to any length to play his fantasy game. And then after that rather fine and promising scenario (as it seemed to me), Sweet Violets turned into plot spaghetti. So my point is that Scarlett had already incorporated some very powerful plot elements and ballet character motifs, which were fully able to sustain the entire piece (the better for losing 10 minutes). Perhaps I overstated it when I recommended in my Arts Desk review that he cut half the characters – no Eifman he – but (as I think John Macfarlane perceives in his sets) I feel, on one viewing, that this is an expressionist ballet struggling to get out of a soap opera.

I can’t bear not knowing what’s going on in a narrative ballet, so I invariably read the synopsis in advance (if there is one – and I reckon MacMillan’s one-act story ballets could do with more programme information) – and, if relevant, the novel/play whatever source the choreographer has drawn on. Is this cheating? Should you feel free to make up your own version of what you see on stage for the first time, while you’re trying to absorb information from the music, set, costumes, dancers (if you can recognise them)?

I reckon you have to pick up as many clues as possible from what the choreographer and designer(s) provide: that includes the prog. note/synopsis, the cast sheet, the costumes, any distortions in the setting, lighting, etcetera. Scarlett provides quite a detailed cast sheet for Sweet Violets: so the Christopher Saunders character is not some rich patron but the Victorian Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury. What is he doing? Read Scarlett’s prog. note. Leanne Cope, violently offed by Thiago Soares at the start, is named as Emily Dimmock, a 1907 murderee – Robert Wood, Soares’ character, was accused of her murder; Laura Morera is named as Annie E. Crook, who was binned for having an affair with Prince Eddy (and possibly a baby). She’s not any old low-life in Sickert’s fantasy.

Yes, the ‘historical’ plot is tricky to follow first time round, but it’s not spaghetti. Scarlett has indeed created an expressionist ballet – but he’s drawn on an existing story, as for example, MacMillan did in Different Drummer, based on a real-life murder story dramatised as a play and opera. Why not accept the choreographer’s source rather than inventing your scenario?

I evidently didn’t make my point clear. I read the scenario immediately after watching the ballet, and enjoyed the specific details of the newspaper story that it follows. But it didn’t make my dissatisfaction with it as theatre go away. My point was that Scarlett had initially (and probably not unwittingly) used some familiar narrative archetypes, generating much resonance in interpretation even for the innocent eye, but the more specific it became the less dramatic it became. Any great theatre (non-verbal or verbal) stimulates the audience to re-interpret and claim for their own experience what the actors interpret of the text of someone else’s experience. Any performance is a canvas that is being much painted over by different perceptions and versions, the writer’s, their subjects’, the collaborators’, the performers’, but ABOVE ALL those of the viewer; it is not going to succeed just because it scrupulously follows a detailed libretto that reads well on the page. Personally I need the instinctive stimuli to be strong enough to survive mundane details. And I think most people have agreed that Scarlett’s ballet is clotted. The question is how he de-clots it.

Jann Parry notes:

“Scarlett has indeed created an expressionist ballet – but he’s drawn on an existing story, as for example, MacMillan did in Different Drummer, based on a real-life murder story dramatised as a play and opera. Why not accept the choreographer’s source rather than inventing your scenario?”

Expressionism is a useful place for artists to hide. It usually means that their material is not malleable in a literal way. I have not yet seen Sweet Violets – so comment in relation to Different Drummer. Even knowing the source play and opera the ballet was unintelligible. Would a programme note have helped? No. The piece should be expressive in its own terms. That will be different for whatever the author intended because each viewer’s perception is different.

Did Scarlett set out to create an expressionist piece or a narrative one? I hope to tell when I do see Sweet Violets, but I won’t be reading the programme note.

For an evening of new choreography the archaeology was clear to see.

Christopher Wheeldon’s Polyphonia evoked Balanchine, Petipa and Ashton. The massed formations, in the second section of Wayne McGregor’s Carbon Life, are pure Grigorovich. In Liam Scarlett’s Sweet Violets we are tossed straight in to what could be the bedroom scene in MacMillan’s Manon without knowing how we arrived there.

I am not clear whether Scarlett intended to creative a narrative ballet or not. The way in which characters appear from behind the mirror (in a way that is not fully resolved in the staging), initially the first victim (I think) and later Jack suggests that Scarlett is aiming for an hallucinatory effect – similar to Tatiana’s dream in Onegin.

The ballet would register more strongly in a smaller theatre. John Macfarlane’s designs skilfully accommodate multiple locations using unconventionally shaped segments of the stage – but Scarlett’s use of these spaces does not project.

The use of the Rachmaninov is musical and supports the action surprisingly well though is intractably long in places. The music hall scene drags for all its clever use of a double front. Scarlett would do better to commission a new score.

Scarlett’s influence is clearly Kenneth MacMillan – with all the seams showing in how characters arrive on stage and their motivations. If Scarlett is aiming for an expressionist treatment – I suspect he may be – then fewer characters – and perhaps different facets of woman-as-victim portrayed by the same dancer would be stronger dramatically.

Sweet Violets and Carbon Life are both over produced and under directed. Scarlett has the excuse of youth. With McGregor you wonder whether he wants his choreography to be noticed, so dominant are its trappings. Yes I know it’s conceptual, intended as more than the sum of its parts – but here the music has an energy of its own that leaves everything else standing – save for a duet for Steven McRae and Sarah Lamb that has stretch and poise and something approaching lyricism.

Polyphonia, on a first viewing, I found rather arid and passionless. The magisterial control of Sarah Lamb and Johannes Stepanek registered most, amplified when joined by Yuhui Choe and Ludovic Ondiviela as a quartet. Ondiviela and Dawid Trzensimiech had more than the required energy and vivacity for their duet. Scintillating.

But good to see – and learn that the grazing flamingos in Wheeldon’s Alice’s Adventures are a quotation from Polyphonia. I prefer Christopher Wheeldon’s Continuum, also to Ligeti, for its spatial patterning. It would fit the RB like a glove and be a better acquisition than Fool’s Paradise.