A Life in Dance

theclivebarnesfoundation.com

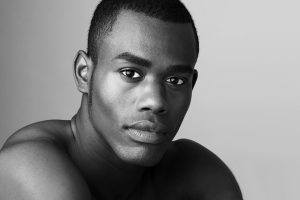

2012 Finalists

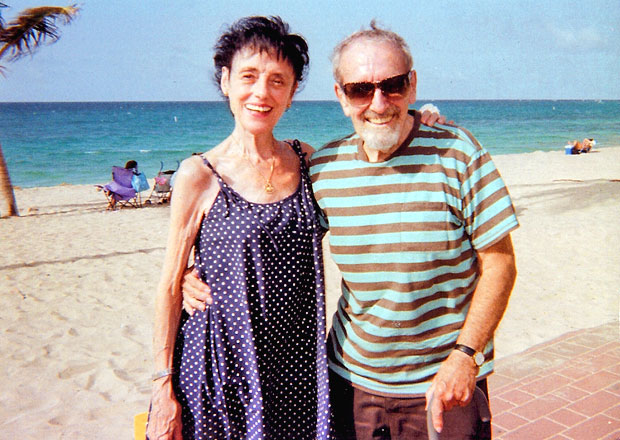

Valerie Taylor-Barnes, wife of the late dance, theatre, and sometime opera critic, Clive Barnes, is a frequent, graceful and gracious presence at performances around town. She first entered the orbit of her future husband when she was a young soloist at the Royal Ballet; he even wrote a short piece about her in the British magazine Dance and Dancers. But it was not until much later – decades later in fact – that the two became friends. They married in 2004. By then, both had long since left London for New York; Taylor was teaching ballet and Barnes was one of the city’s most prominent dance and theatre critics, first at the New York Times, and later, for over thirty years, at the New York Post.

After his death in 2008 Valerie Taylor-Barnes decided to create a foundation in his memory, with the aim of encouraging budding artists by acknowledging their promise with an award. Since 2010 the Foundation has given out two yearly prizes, one for an actor or actress, the other for a dancer. Throughout the year a selection committee (which includes Damian Woetzel, Alexandra Ansanelli, and Taylor-Barnes herself) meets to discuss performances and possible nominations. Each of the winners receives five thousand dollars, the nominees, five hundred. So far the winners have included Nina Arianda, star of Venus in Fur, and Chase Finlay, a gifted young danseur noble at New York City Ballet. Much of the money for the prizes – and for the ceremony at which they are announced – comes out of Taylor-Barnes’ own pocket. The idea for the prize was hers; in a recent interview, when asked what her husband would have thought of it, she said, with characteristic modesty, “I think he’d have fancied it.”

This year’s nominees, who include the lovely, lyrical Lauren Lovette of New York City Ballet and Rob McClure of Chaplin, were announced in mid-October; the final selection will be made public at an award ceremony on December 10, to be held at the Walter Read Theatre. (2012 finalists)

Taylor-Barnes and I met for coffee and cake in her airy, book-filled apartment in Chelsea, the same apartment she shared with her husband and which she now shares with a personable beagle by the name of Joshua. A lifetime of dance photos line the walls and litter every surface; several are of Margot Fonteyn, much admired by both. Valerie spoke about her life as a dancer, about her decision to move to New York, and about keeping up with Clive.

Tell me about your career.

I started [at what was then Sadler’s Wells, later the Royal Ballet] when I was sixteen. I went to the school in Baron’s Court in London, and I went through school up to my high school exams, because my parents said “you’ve got to do that before you do anything else.” So I was at a proper high school, where people graduated and went to Oxford. They gave me a special program. I had private lessons twice a week with Phyllis Bedells. She was very well known in her time, in the late twenties. Also, I had a scholarship with the Royal Academy of Dance where we had classes from people like Karsavina and Itzikovsky; all the elderly Diaghilef dancers came and taught us. I got the scholarship when I was nine, so I really didn’t understand Itzikovsky or what he was talking about, but it was all a great honor. It was a very mixed kind of upbringing as far as ballet was concerned until I went to the Royal Ballet School. And then I was there for a year and a half. I had a man called George Goncharov; he didn’t like me very much, I don’t know why (laughs). He had a favorite, you know. I didn’t stay in the school for very long. I was there for half a year after my GCE [General Certificate of Education] which was the final exam, and then they needed people to fill in at the company. I was very quick at picking up steps, and that’s how I got into the company so soon, at seventeen. They kind of shoved me on as a student, and I managed to pick up fast. [Taylor joined the Royal Ballet in 1948.]

© Marina Harss.

What were some of your first experiences as a dancer?

One was in [Massine’s] La Boutique Fantasque, and much to my shame, we had to get on the boy’s backs – they were kneeling down – and sit like this [strikes an elegant pose] and I slowly slid off. I thought: “There goes my career.” In 1949 there was the first tour to the US. I was in Sleeping Beauty; I think I was in the Prologue, as a court lady. In the second act, I was a knitting lady and I got a review, because I dropped my knitting. The garland girls came on and they all got their feet caught in the wool. It was a wonder they kept me on. And my hat came off in the farandole, and that was also noted.

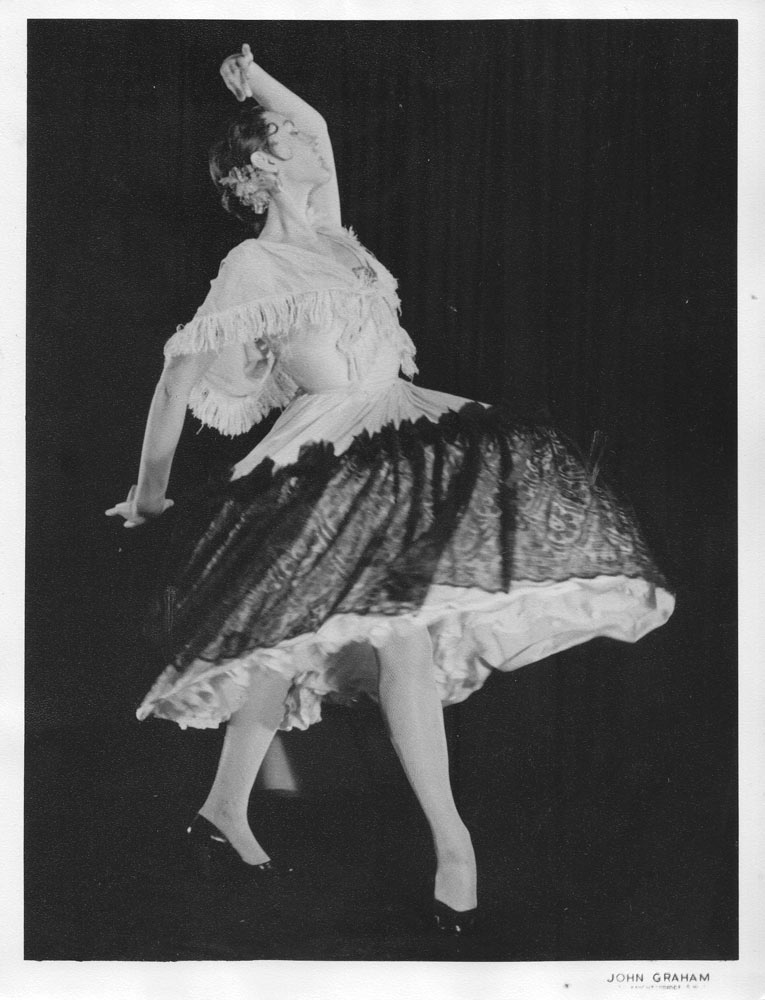

What were your favorite kinds of roles?

Of course, like most young dancers, I wanted to be a classical dancer, but I think really my forte was demi-charactère and character roles. I danced the Miller’s Wife in [Massine’s] Tricorne, which I loved. Growing up, I did a lot of piano and elocution – most kids did – and I loved that, and I loved the piano too. I think my parents would have been happier if I’d said I wanted to be a pianist. We did Les Sylphides with Grigorief and Tchernicheva, she was just extraordinary. I was the Prelude. It was an amazing experience to learn it from her. I couldn’t look at a different version of Sylphides after that, even though I know Fokine had several.

Did you come from an artistic family?

My father played a lot of music, but he was a businessman, and my mother was a stay-at-home mum. But they loved music and my mother went to the theatre a lot. As a child I was always taken to plays and concerts. I was the youngest by eleven years. My brother was nineteen years older than me, and my sister was eleven years older. Then there was me. My brother died when I was ten, in the war, and my parents adopted his eldest son, so it was like I had a little brother.

How did you decide you wanted to be a dancer?

I don’t think I really decided, I just loved dancing. My sister was really keen and she was babysitting me, so she took me along, and I joined in at the ripe old age of three.

© John Graham. (Click image for larger version)

Were you drawn to the music?

I think so, that always was my inspiration.

Was there a particular choreographer you enjoyed working with when you were in the company?

Ashton, without doubt. I loved all his work. He was a wonderful, wonderful man, absolutely lovely. He was very, very sensitive. I never knew him to lose his temper, with all the trials and tribulations; he was always just terrific, with a great sense of humor. I learned, well, I suppose everything I knew about the theatre from him. He was very open and generous with everything. His way of choreographing was wonderful because he would ask us to join in. He would say: “Just do a step to that,” and even if he didn’t use it, you felt like you were partaking in what was going on. It kept everybody interested. I think everybody loved him. He was an amazing man. I remember very clearly, working on Daphnis and Chloë. I mean, the music is so wonderful.

You have no idea what it was like with Ninette de Valois. She ruled that company with a rod of iron, and we were all terrified of her, but on the other hand, we admired what she was doing, because she built that company. She would probably be astonished now because there are hardly any English dancers. In those days, we were all English, or from what were called the Colonies.

Did Clive ever write about you?

Yes, I have a piece that he wrote. He was writing for Dance and Dancers; they had a column called “Dancer You Will Know,” and he wrote one about me when I was twenty-one. He was only twenty-six or something. There wasn’t a great deal of difference. I was scared of him, actually. We didn’t get any kind of coaching in my day; we didn’t really know what was coming off, or whether you were on the right track. There was one critic who took a great interest in me, A.V. Coton. He was a very very good writer. And when I danced Tricorne he had an enormous amount of stuff to tell me, which was so very welcome. He wrote me a letter, and he said “could we meet for tea or something,” and I did. I was so grateful because there were things I was doing and he told me, “that doesn’t really work,” and made another suggestion, all the way through. Of course, nowadays they have coaches.

So what did Clive say about you?

It was a whole thing about my career, and it ended – and I never let him forget it – with something like, “she will probably never lead a company, but she will be, given the right opportunities, what is anatomically known as the backbone of the company.” I was only twenty-one, and I had these dreams of being a classical dancer. You have to take what you get, don’t you.

When did you meet?

Not until I came over here, in 1980. His [second] wife [Patricia Amy Evelyn Winckley] and her twin sister were fans, and they used to stand outside the stage door, and I remember we were in Chicago and we came out into the freezing cold weather, and I said “my god, those girls are here.” I like his wife, she’s a very nice woman. He married [Joyce Toman] when he was nineteen, and she was a musician, and they were married for about ten years, and then he married Patricia, and they had two children. And then he married Amy [Pagnozzi], who was about thirty years younger, and then he lived with Elizabeth Kaye, and that fizzled out, and then he met me. I had known him just to say “hi, hello, nice to see you.”

© Derek Allen. (Click image for larger version)

Why did you retire from dancing?

I had a very bad back problem. I had a performance, and they gave me an injection to deal with the pain, and of course it was wonderful, but when it wore off, it became a chronic condition. And the other thing was, I became very tired of living my life around my performances, my shoes that had to be darned, my tights that had to be washed. In those days it somehow took up the whole of one’s life. I did try to have an outside life, but I was always busy. I was thirty-one.

What did you do next?

I went back to my original teacher at the Royal Ballet School for six months to learn all about teaching. She used the Royal Academy of Dance syllabus as a basis. I had no vocabulary, because we didn’t say pas de bourrée and jeté, we just said one of these and one of those. I did that for six months, and then the Royal Academy invited me to be an examiner. I was a bit nervous about it because the others were about thirty or forty years older. They told me: “You have to wear a hat.” (laughs) I had an interview and they put me in a chair with my back to this enormous electric fire. And I said “I have one query: can we please change the rules because I can’t concentrate with this hat on.” So they did. I did that for sixteen years. I came over here in 1980.

Why did you come to the States?

Well, my mother died. And I really needed to get away from everything in England.

You had never married.

No, I never married until I was with Clive. Everyone used to look at me and think, “poor thing, she never married.” (laughs) I was seventy-three when I got married to Clive. I had my life. I wasn’t looking to get married at all; it was the last thing on my mind. And Clive too. Because he had only lived on his own for seven years, after Elizabeth left. And he was very proud of himself.

I came here planning to stay a month – I have a niece in Connecticut. And there was a dancer with the Royal Ballet called Peter Franklin White, and he was teaching in Boston. And somehow he found out that I was here and he called me and said, “would you like to come and teach?” I taught there for three or four months, and when I finally asked, “what’s happening with my working permit?” I found that all the papers were still in the drawer. Luckily for me, the head of the board was a lawyer, and he found me a lawyer in New York. I managed to get my permit. And then I became a citizen in 1992, because I wanted to vote for Bill Clinton. I immediately registered as a Democrat and voted for him.

Did you continue to teach in New York?

Yes, I had quite a little industry going. I taught a lot of kids from SAB [the School of American Ballet], because in those days, it was the fashion among the students to have private lessons. When I first came over, I went to watch classes at SAB, and I remember the chief secretary, a big Russian lady, asked me, “how did you find the classes?” And I said, “well, I don’t really understand them. I’d like to come back another time.” Then I went to the Joffrey, and I watched Robert Joffrey teach, and it all made sense to me. His teaching was the same as I had experienced all my life. I rented space, and I used to go with my tape recorder over my shoulder. I’ve done all kinds of things since then, I taught at the High School of Performing Arts, and then they asked me if I’d like to go to Martin Luther King High School. There I was, with this English voice, teaching classical ballet. I had had no idea how difficult the conditions for these young people were. It boggled my mind. I led a demonstration in the school for studio space, because they put us on the stage, and the students couldn’t concentrate. I was chastised by the principal. He said, “you really shouldn’t behave like this,” and I said, “well, you shouldn’t make these kids dance on a floor like that in the freezing cold theatre. Everything has a space.” So we got a studio and the students were thrilled.

© Valerie Taylor-Barnes.

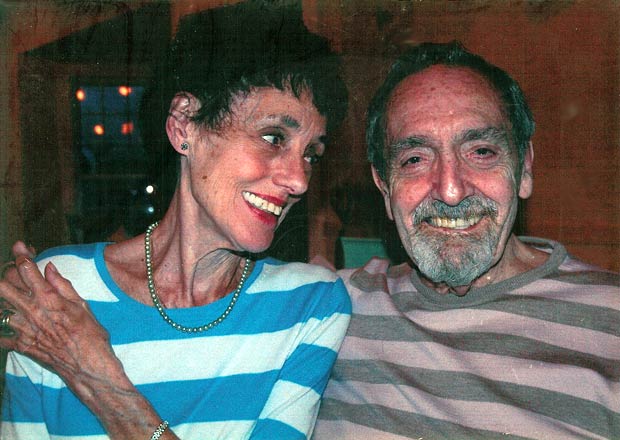

Did your life change dramatically when you and Clive became a couple?

Yes, it did. By then I was teaching at Marymount – I had been at the Dance Theatre of Harlem with Arthur [Mitchell] for eight years. Then I went to Marymount Manhattan College. That’s where I was when I started going out with Clive. It was fine, because my classes were in the daytime, so I could go out in the evening.

Were you going out every night?

More or less. I loved it. Dance, theatre, and he did opera as well. I saw everything. It could be, let’s see: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday twice, Thursday, Friday, Saturday twice, and Sunday afternoon, nine shows. That was the maximum. It often wasn’t as much as that. I had an awful job keeping up with Clive. He had incredible energy. I did learn how to do it, but at first I would sit there like this (slumps). When it was two plays in a row, I found it almost impossible to stay alert at the second performance.

What drew you to him at that point?

It was something that I can’t really explain. It just kind of worked, like meeting myself, in a way, in masculine form. We just kind of clicked.

Did you have the same taste?

Mostly. I didn’t have tremendously strong opinions about theatre at first. Of course I did have strong opinions about ballet. Clive preferred coming home without having conversation about it; he wanted to write before we talked, which made a great deal of sense. I had been used to saying, “what did you think?” Clive didn’t much like talking to people at intermission.

Maybe having you there was also a way of protecting himself from those kinds of conversations.

Perhaps it was, yes.

What qualities did he particularly admire in a dancer?

Well I think that mysterious thing called artistry. The last person he wrote about – I have a very fond feeling for him as a result – is Daniil Simkin. Clive thought he was like a young Baryshnikov. He loved him. He felt the same about Kathryn Morgan of New York City Ballet. She was so outstanding and Clive had great hopes for her.

Lauren Lovette [one of this year’s Clive Barnes Award nominees], at City Ballet, has something special.

I think so, yes. She’s one of our nominees this year. Another one is Ashley Murphy, of Dance Theatre of Harlem, she’s amazing. And Steven Melendez [of New York Theatre Ballet]. He’s a real artist. I saw him in José Limon’s The Moor’s Pavane, and I thought, my goodness, that guy has something, a tremendous conviction.

How does the Clive Barnes Foundation select its nominees?

Our panelists suggest people. We have Alexandra Ansanelli, we have Damian Woetzel, George Dorris, Arthur Mitchell, Craig Wright, and me. We’re the dance people. And there’s a separate panel for theatre. I loved Rob McClure in Chaplin. [McClure is one of this year’s four theatre nominees.] It’s a wonderful performance, all the way through, and he’s hardly off the stage. It made a lump in my throat, I was getting quite emotional by the end.

Did Clive get emotional at the theatre?

No. The only time he got emotional was when Tony Palmer came here for the Fonteyn film. Clive started to talk about Margot and he started to cry. He said, “cut it, cut it,” but of course they didn’t, because they love the tears and all that.

There’s a cash prize for the recipients of the Barnes award, isn’t there?

Yes, five thousand dollars each and the finalists are awarded five hundred dollars each.

You must do quite a bit of fund-raising.

I wish. We try, but we haven’t had a very good response. We had a wonderful response at first, but this year has been poor. We need more exposure. I had a lovely anonymous donation of $25,000. It costs quite a lot to put on the awards ceremony, because I have to pay for the theatre, etc. We don’t charge admission.

And the Clive Barnes Foundation, is that essentially just you?

[Laughs.] Yes, when it boils down to it, it’s only me.

You must be logged in to post a comment.