© Shanghai Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

Shanghai Ballet

White-Haired Girl

Hong Kong Cultural Centre Grand Theatre

25 January 2013

www.shanghaiballet.com

A version of this review previously appeared in the South China Morning Post.

Shanghai Ballet, generally considered Mainland China’s leading company after National Ballet of China, made a long overdue appearance in Hong Kong in January.

The company was presented by a group called the China Ethnic & Folk Culture and Arts Exchange Association, a “patriotic” organization whose raison d’être is at least as much political as artistic. This no doubt explains why the 1960s propaganda ballet White Haired Girl was chosen as the programme.

White Haired Girl and Red Detachment of Women are the most famous ballets to have emerged from the Cultural Revolution. Works of propaganda typical of that period, they are extremely dated and their main interest to an international audience is as historical curiosities. In China they have an iconic status in the country’s ballet history and continue to be performed for ideological reasons (it’s still officially a Communist state, however many luxury goods some of its citizens may buy overseas). Depending on the individual’s experience and viewpoint, they are a source of nostalgia to some Chinese, a painful reminder of dark times to others.

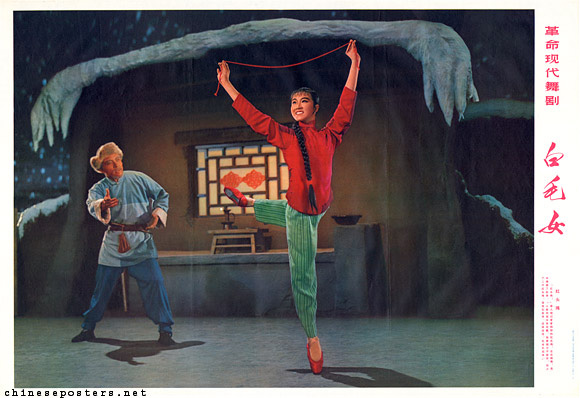

Both ballets have similar stories loosely based on real-life incidents. In each a young peasant girl is abused and imprisoned by the wicked local landlord and escapes to take revenge with the aid of the courageous revolutionary army. In White Haired Girl the heroine Xier’s father is murdered and she is abducted to be a slave in the landlord’s house. After she flees she spends years alone in hiding in the mountains where her hair turns white with suffering, hence the title. Of the two ballets Red Detachment (a staple of National Ballet of China’s repertoire) is far stronger artistically and, despite its cruder (and kitscher) aspects, capable of packing a real dramatic punch.

In White Haired Girl the propaganda is even more glaring. The score consists partly of revolutionary songs (to which the original audience would probably have sung along) and the narrative flow is constantly interrupted by characters stopping to strike poses familiar from revolutionary posters. It ends with an image of the red sun rising and a chorus in praise of Chairman Mao, leaving anyone aware of the horrific events which took place under Mao feeling rather queasy. I also feel it’s a mistake to present the villains as bumbling and comical rather than evil (I found them quite endearing and totally unmenacing) if the hero is going to execute them in cold blood (albeit thankfully off stage) at the end.

Ideological qualms aside, White Haired Girl is an odd bird. The choreography is a hybrid between textbook classical vocabulary and Chinese opera, an idea interesting in itself but here executed with a lack of imagination and sometimes a lack of judgment. The murder of Xier’s father would be more moving if he didn’t fall flat on his back and expire in a way which, while influenced by Chinese opera, in a ballet becomes irresistibly reminiscent of Basilio’s fake death in Don Quixote. The insertion of 19th century-style bravura steps at moments of emotion jars on anyone used to the realism of modern dance-drama. (If a Cranko or MacMillan heroine was reunited with her lover after years of separation and misery, she would not, one feels, break into a series of Italian fouettés to express her joy. It’s a great solo in Corsaire, but not in this context.)

The title role is split between two ballerinas, one portraying the young Xier and the other her subsequent incarnation as the vengeful White Haired Girl. In the first role, Ji Pingping showed herself to be a fast, precise dancer with an impressive line in turns and, more importantly, a fine actress – it is to her credit that she managed to bring so much emotional depth despite the limitations of the production. Fan Xiaofeng as the White Haired Girl and Wu Husheng as the hero are both handsome, long-legged dancers with strong techniques and big jumps but limited expressiveness. There were some lively Chinese opera acrobatics from the male corps and it was a pleasure to see the character roles performed by artists of the right age, one of the company’s strengths.

Overall, based on this viewing Shanghai Ballet has well-trained dancers and a good technical standard, if not in the same league as National Ballet of China or Hong Kong Ballet. The repertoire is varied and includes some original productions – I was intrigued to see that a new full-length Jane Eyre was created last year – and I look forward to seeing the company again in work which gives a better idea of its true ability, style and range.

You must be logged in to post a comment.