© Erik Tomasson. (Click image for larger version)

San Francisco Ballet

Digital Programme 05: 7 for Eight, Snowblind, Anima Animus

★★★★✰

22 April 2021, streaming on sfballet.tv until 12 May 2021

www.sfballet.org

The fifth San Francisco Ballet (SFB) digital offering includes two works by English choreographers, Cathy Marston and David Dawson, commissioned in 2018 for the company’s Unbound festival of new works. The third ballet, 7 for Eight, is by the company’s veteran artistic director, Helgi Tomasson, created in 2004. I had missed SFB’s London season at Sadler’s Wells in 2019, so was pleased to catch up with ballets brought together for this digital triple bill.

Cathy Marston’s Snowblind replaced her latest commission for SFB, Mrs. Robinson, cancelled because of Coronavirus restrictions. Snowblind, her first for the company, is based on a 1911 novella by Edith Wharton, Ethan Frome, about a marriage gone cold in a Puritan society. It was set in New England, around the turn of the 20th century, so Marston chose music by New England composers, Amy Beach and Arthur Foote, from around that period. The arrangement is by Philip Feeney, who contributed his own compositions. Minimalist designs are by Patrick Kinmonth, who collaborated with Marston in adapting the bleak story into a half-hour ballet.

Because the events take place in winter, Marston uses a 13-member corps as snowy elements to set the scene, having them drift or whirl across the stage at key intervals. Both sexes wear identical dark bodices and flowing, white-dipped skirts, distinguishing them from a separate chorus of villagers. Marston’s story telling is clear from the start, when she establishes the marital relationship between impoverished farmer Ethan Frome and Zeena, his sickly wife. (Apparently, she was a hypochondriac, tricky to establish in ballet terms.) Zeena, Sarah Van Patten, is brittle and needy, though not as frail as she appears. When she raises a leg high in arabesque, Ethan, Ulrik Birkkjaer, bends it down as though impatient with her nagging demands. During their opening pas de deux, she seems a burden he has to bear.

© Erik Tomasson. (Click image for larger version)

Brooding and fretful, he sets out to spy on a youthful party of villagers. In their midst is a high-spirited girl in a pink-red dress, Mattie Silver (Mathilde Froustey), the Frome’s home help. Ethan escorts her back to the farmhouse in the snow, reverting to being as playful as she is. He swings her round like a child, watches her make snow angels and lets her jump onto his back – an omen of what it is to come. When they return, Zeena spots the attraction between them and claims her husband possessively. Mattie is instructed to don her apron and start scrubbing, the Cinderella of the household.

Zeena berates her angrily, clawing on pointe like a praying mantis. Ethan enters with a group of farmhands, who appear to demand money, arms folded in disapproval at the discord in the family. Up until this point, Zeena has appeared the icy-hearted villain of the piece. When Van Patten looks at Birkkjaer, however, a camera close-up reveals the painful reproach in her eyes as Mattie helps her upstairs to bed. She is vulnerable as well as resentful.

Down below, Ethan punches the air in frustration. When Mattie joins him to declare her love (or infatuation), he reacts like a teenage Romeo, paddling palms with her, flying her ecstatically in the air and daring to kiss her, before suggestively removing her apron. Zeena catches them at it and takes Ethan to her side, demanding his support. Mattie, distraught, runs outside to be swirled amidst the stormy corps, a threatening horde very different from Nutcracker snowflakes.

When Ethan joins her, Marston’s story telling fails, for without a synopsis, it would be impossible to tell that Mattie and Ethan have sworn a suicide pact, ‘throwing themselves into the elements’. In the novel, the lovers deliberately run their sled into a tree at the bottom of a slope, resulting in terrible injuries. In the ballet, the agitated corps catch and hurl the frantic pair repeatedly, before abandoning them sprawled on the ground, seemingly lifeless from hypothermia.

© Erik Tomasson. (Click image for larger version)

The final scene is redeemed by Van Patten’s conflicted reactions as Zeena discovers the entwined bodies in the snow. A stillness descends, accompanied by the plangent piano notes at the start of Arvo Part’s Lamentate. Zeena must decide whether to shun the pair or call for help, whether to resuscitate Ethan or leave Mattie to die. As the villagers arrive, Zeena covers her eyes, snow blinded, and tries to make the witnesses turn their backs on the shameful sight. Then, overcome by grief and compassion, Zeena embraces both barely alive bodies in an interlocked triangle. They are bound together, wrists knotted, bearing each other’s weight as they twist and revolve.

Thanks to Van Patten’s expressive face and gestures, Zeena appears in turn triumphant and forgiving. Ethan and Mattie are at her mercy, dependent on her. She holds helpless Mattie in her arms like the child she never had. Ethan bears Mattie on his back, as he once had to do with Zeena. In the novel, he is punished by being lumbered for years to come with his ailing wife and paralysed Mattie, with no hope of escape from his guilt. Marston offers a possible loving atonement for him and Mattie, instead of a living death.

Snowblind is a powerful piece, well-acted as well as danced by the three principals, who invest their roles with sympathetic understanding of the characters’ plight. But there’s no real context to their tragic story. The corps of villagers have little to contribute once the party scene is over; they are not established as the disapproving New England Puritans of Wharton’s novel. The snowdrift corps is something of a Marston trope, intended to be symbolic while being capable of intervening literally in the action. Ethan even dances a brief pas de deux with one of the female snowflakes on his way to meet Mattie, before a blizzard of snow inflicts physical retribution on them both.

David Dawson burdens Anima Animus (his first work for SFB) with statements about Jungian notions of male and female archetypes of the unconscious mind, while having his ten dancers resemble birds in flight. They are costumed by a dancewear designer, Yumiko Takeshima, in sleek outfits with contrasting segments of black and white. A strip along the spine emphasises arched torsos as the dancers run and leap in split jetés, arms reaching up and back. Running is the default mode, matching the pulsing rhythms of Ezio Bosso’s Violin Concerto no 1 (similar to his score for Christopher Wheeldon’s Within the Golden Hour).

© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

Ten dancers skim across the stage, almost silhouetted against the backlit white square of James Otto’s set within a black frame. Distinctive physiques reveal that the two leading women are Sylviane Sylve, tall and long legged, and Maria Kochetkova, petite and flexible. In the second movement, both are manoeuvred in matching trios by men who do little but run, catch and raise, with no opportunity to dance. The most spectacular lift involves Sylve holding herself suspended horizontally on a man’s upstretched arms as he runs off with her into the wings. A ‘bum’ lift, with Kochetkova poised aloft a man’s arm, is included for good measure. The imagery of women soaring as angels above earthbound men is a device used by John Cranko and Kenneth MacMillan, among others, in requiem ballets rather than abstract works.

Dawson’s main aim was to show off the ‘physical emotional virtuosity’ of SFB’s dancers. ‘Emotional’ is up to the audience to interpret, while physical ability is made evident in multiple turns and acrobatic extensions. Dawson keeps the hyper-elongated lines balletically elegant instead of distorting them, as Wayne McGregor is prone to do. Speedy, space-devouring choreography favours the women on pointe, since the men are given few virtuoso opportunities: their male Animus drive has been transferred to the bravura women. There is a limited vocabulary of steps in the ballet, in any case, thanks to the repetitive running motifs. The dancers shine, nonetheless, as Bosso’s EsConcerto builds to a final climax.

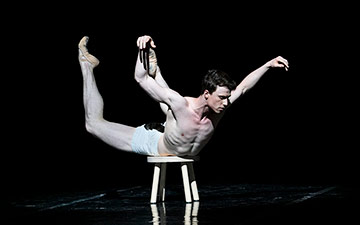

© Erik Tomasson. (Click image for larger version)

Helgi Tomasson’s 7 For Eight, the opening number in Digital Programme 5, also uses a restricted vocabulary in his neo-baroque choreography to keyboard concerti by JS Bach. There is no intricate batterie – just some cabriole beats for the men, who get their share of dancing as well as courtly partnering. The eight dancers are dressed in black, the women in beaded bodices with low-cut backs and short diaphanous skirts (designs by Sandra Woodall). The first adagio duet for Yuan Yuan Tan and Tiit Helimets has her swooning in and across his arms until he carries her off solicitously, to reappear later in the suite of dances as if continuing their pas de deux. In between comes a sprightly duet for Vanessa Zahorian and Gennadi Nedvigin, followed by a trio and double duets. When men dance together, they share the space but don’t touch. When they partner a woman, they rarely dance alongside her, too preoccupied with supporting her every move.

Taras Domitro has a showpiece solo, starting off mock-heroically before darting around the stage to a harpsichord concerto arranged for just one keyboard. Lots of swift sissonnes and cabrioles, a manège of split jetés, a return to heroic posturing and a cheeky smile as he spins into the wings. Back come Tan and Helimets, formal, tender and very solemn, as though in mourning. They then joined three lively couples for a cheerful, bouncy finale. There’s no through narrative, simply a skilfully crafted response to seven selections of Bach’s concerti played by solo pianist Mungunchimeg Buriad. Thanks to video recordings made before Coronavirus restrictions, all the ballets were danced to live music by SFB’s orchestra, conducted by music director Martin West.

You must be logged in to post a comment.