© Hungarian National Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

Tribute to Laszlo Seregi

Choreographer & Hungarian National Ballet artistic director

London, Hungarian Cultural Centre

13 May 2013

www.bbi.hu/en

www.opera.hu/en/balett

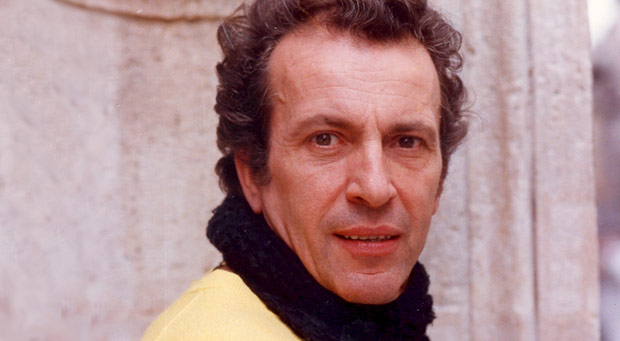

‘Laszlo Seregi was witty, amusing and larger than life,’ stated Mia Nadasi at the opening of an evening that was to celebrate the life of one of the most famous names in Hungary’s cultural crown. A respected and well-loved dancer, choreographer of international repute and artistic director of the Hungarian National Ballet, Seregi’s artistic and lively personality influenced and promoted a deep love for classical ballet throughout his country – and abroad also. He died on 11th May 2012 at the age of 83, so, one year later, the Hungarian Cultural Centre in Covent Garden hosted a tribute to his memory.

Hungarian National Ballet in Laszlo Seregi’s Romeo and Juliet – excerpts from acts 1 and 2.

The evening was organized by Mia Myrtill Nadasi, a former ballerina of Hungarian National Ballet and a well-known actress of stage and screen, whose parents, both dancers, had been instrumental in determining Seregi’s career. She guided us with humour and affection through a potted history of the dancer’s interesting life, showing a selection of clips from three of his most famous Shakespearean ballets, and inviting two young actors to give relevant readings from those plays.

© Bela Mezey. (Click image for larger version)

Laszlo Seregi, known by the diminutive of his name, Laci, was born in Budapest on 12th December 1929, into a poor family of tinsmiths. As a child he loved music and art, but it was when he saw the choreography of Mia’s father, Ferenc Nadasi, that he was overcome with the desire to dance himself. Later, while working in a factory as a warehouseman, he decided to join the Army Ensemble where he could participate in folk dancing. With little professional training, the eighteen-year-old young man said of the audition that: ‘My talent was to copy’. He was accepted and joined the Army Ensemble (founded on the Soviet Red Army Ensemble with its body of soldier singers, dancers and musicians) and it was here that he learned not only folk dancing but also the basics of classical ballet taught by Marcelle Nadasi, Mia’s mother, who was ballet mistress; and that was when Seregi’s great love of dancing truly began. Despite his lack of experience, he was a quick learner and it was in his years with the troupe that he started to develop an interest in choreographing. Seregi performed and toured extensively with the Ensemble for 8 years. However, there were troubled times back in his homeland, and in 1956 came the Hungarian uprising against the Soviet regime. The Army Ensemble was on tour in China at the time and could get little information on what was happening back in their home country. It was impossible to return as planned, so the whole troupe travelled on the Trans-Siberian railway from one side of the vast USSR to the other, a journey that took 15 days, and when they arrived home, they found that the whole Army Ensemble had been disbanded. Many people, including several solo dancers, from the National Ballet Company had fled the country, so it was decided to look at the boys from the now defunct army troupe to see if any could replace those who had left. Three boys, including Seregi, were accepted and he joined the Hungarian National Ballet as a character dancer, admitting that he didn’t enjoy being in the corps de ballet.

© Bela Mezey. (Click image for larger version)

Seregi soon discovered that he had a great talent for creating ballets and by 1965 was choreographing the ballet excerpts in operas. In 1968 he created the greatest of his works – Spartacus – the same year as Yuri Grigorovich’s epic production for the Bolshoi Ballet. Seregi’s version was considered the closest to the story, though its future looked decidedly transitory when the composer Aram Khachaturian initially panned it. Coming to see the finished work, he found that Seregi had started his production with the final scene of the scenario – the crucifixion of Spartacus. So, instead of using the music in the order that the Georgian composer had created, the orchestra was playing the ballet’s concluding chords – not the first – when the curtain lifted. Khachaturian stormed out of the building affronted that his score had been tampered with. However, the ballet proved a huge success with the public. Seregi’s choreography told the story, capturing the Soviet heroic style along with elements of Hungarian folk culture, and it won the top award at the Champs Elysees Festival in Paris – at which point Khachaturian relented. The ballet was taken into the Australian Ballet repertoire with Gary Norman as Spartacus and Ross Stretton as Crassus. Seregi continued choreographing, producing some fine full-length works, including his great Shakespearean ballets. He became artistic director of the company from 1977-84.

Setting the Shakespearean mood for us, were Jennifer Higham and Dan Winter, two talented actors, who enacted scenes from the three plays-cum-ballets that we were to snatch glimpses of that evening. With no props and just intonation and inflexion to express their different characters, the two conveyed their roles with great power and effect.

© Balassi Institute. (Click image for larger version)

On the screen we saw short scenes from Seregi’s ballet Romeo and Juliet – one scene being the power-packed moment when Juliet takes the poison, which apparently made the Queen of the Netherlands cry when she saw the ballet. Another clip showed an athletic solo by the green-tasselled unitard-clad figure of Queen Mab. His Midsummer Night’s Dream initially carried a warning, stating that it was: ‘the most erotic ballet,’ and to ‘Leave the children at home.’ Seregi’s last ballet was ‘The Taming of the Shrew’ which was created in 1994 after he had suffered a near-fatal heart attack. Grateful to the doctor who had saved him, the choreographer asked what he could do to repay him. The doctor’s answer was to create one more Shakespeare ballet. So Seregi returned to work at the theatre and choreographed this witty masterpiece. One of the clips we saw was when the ‘Shrew’ was well on her way to being tamed, and nearly ready to serve her master. The set contained a bathtub with dry ice foaming over the top, and the split timing of the couples’ choreographic moves was slick and humorous. Then Mia read the famous final Katharina speech before we watched the final pas de deux.

© Hungarian National Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

The evening was a filled with happy memories and one that Laci would have enjoyed immensely. I had seen several of his works when living in the Soviet Union in the ‘70s and ‘80s and had enjoyed the exuberant pace and lively characters he created. It was obvious that they were the works of someone who was ‘witty, amusing and larger than life.’

You must be logged in to post a comment.