© Stephanie Berger, 2011. (Click image for larger version)

Akram Khan Company

The Silent Burn Project

Streamed online via the company website & YouTube

4 October 2020

www.akramkhancompany.net

This three-hour compilation of dance films, interviews and discussions celebrates Akram Khan’s burning desire to speak out to a wide audience on the occasion of his company’s 20th anniversary. As a young Kathak dancer, he was required to be silent and obedient. Once he established his own company in 2000, he found his voice as a choreographer as well as performer. In The Silent Burn Project, he is eloquent as a speaker – yet even more so as a creator of theatrical dance.

There are only 25 minutes of dance and rather more of music performances, in specially filmed extracts during the programme. The rest of the time is given over to reminiscences, backstage glimpses, discussions and tribute to Khan from his collaborators. These include Sylvie Guillem, Danny Boyle, Antony Gormley, Jonathan Burrows, Alistair Spaulding and Michael Hulls. At times, the compilation feels rather like Wim Wenders’s 2011 documentary film, Pina, about the late Pina Bausch, with contributions from her company members. Fortunately, Akram is still very much with us, even if retired from dancing. In a recently filmed solo, he provides the epilogue to his Silent Burn Project.

When Bausch invited Khan to take part in a festival in 2004, he told her that he didn’t want to be categorised as a South Asian creator/performer. He wants his work to be universal – and thanks to his participation in the 2012 Olympics closing festival, at Danny Boyle’s request, he has reached an audience of many millions. He took part in person, having just recovered from a ruptured Achilles tendon. When a crass politician asked how Khan’s cast of multifarious dancers could represent modern Britain, Boyle riposted: ‘This IS modern Britain.’

Khan and the company’s co-founder and executive producer, Farooq Chaudhry, recalled their early days in setting up the company. They described their younger selves as naive and ambitious, trusting each other to question where they might be going and what audiences they wanted to attract. Though they diverged at one period, they came back together as friends, both with children and ageing parents: ‘We didn’t give up.’ They intend to persevere with deeply thought work that affects people who aren’t just dance lovers, all without repeating or imitating what Khan has already achieved.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

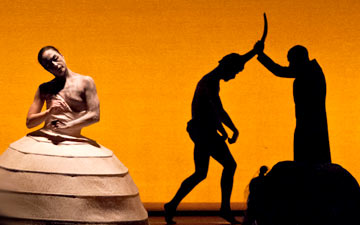

The range of his work was illustrated by dancer Theo Lowe, alone in a ruined church in Norfolk, agonising over God’s instruction to Abraham to sacrifice his son (from iTMOI), by Joy Alpuerto Ritter holding a bamboo pole between her clenched teeth and Ching-Ying Chien atop a Dover cliff (both excerpts from Until the Lions) and Yen-Ching Lin being washed by wind and waves on a Taiwan seashore (from Vertical Road). Khan himself is seen as a shell-shocked soldier in Xenos, his last solo performance.

Backstage footage with dramaturg Ruth Little and rehearsal director Mavin Khoo emphasises how committed the performers have to be, investing themselves in their roles, keeping going beyond exhaustion. Khan’s creative process enables all his collaborators to contribute from the start, with musicians and designers playing an important part. Vincenzo Lamagna speaks of his scores; percussionist B C Manjunath drums and chants in front of an Indian temple; Sohini Alam sings as she walks along Brick Lane in London; Nina Harries plays her version of Mozart’s Lacrimosa on her cello in Tottenham Marshes; David Azurza laments amongst the charred ashes of a forest in France. All the filmed footage of performances under lockdown is sombre, with barely a hint of colour. (Outdoor films are by Maxine Dos and Lorenzo Levrini.)

© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

Two video-call sessions are given over to lengthy discussions by academics, activists and artists on themes of otherness and spirituality. The four participants in ‘Clouds of Witness’, speaking about racial and cultural discrimination of many kinds, admitted that they were often struggling to analyse the layers of what they and others have experienced. Misty Copeland, principal ballerina with American Ballet Theatre, described her conflicted position as a much-publicised role model for Black American dancers while aware she was still regarded as ‘other’.

The participants in the ‘Hijacking God’ discussion of religion had an even harder time in finding a language to define the divine, other than that dance could be a pathway to experiencing it. Khan and Mavin Khoo had previously spoken of the spirituality of Indian classical dance during a recording of an intensive training session with young dancers, instructing them to go beyond technique to ‘a greater narrative.’ They need to know why they are dancing instead of just doing what they have learnt.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

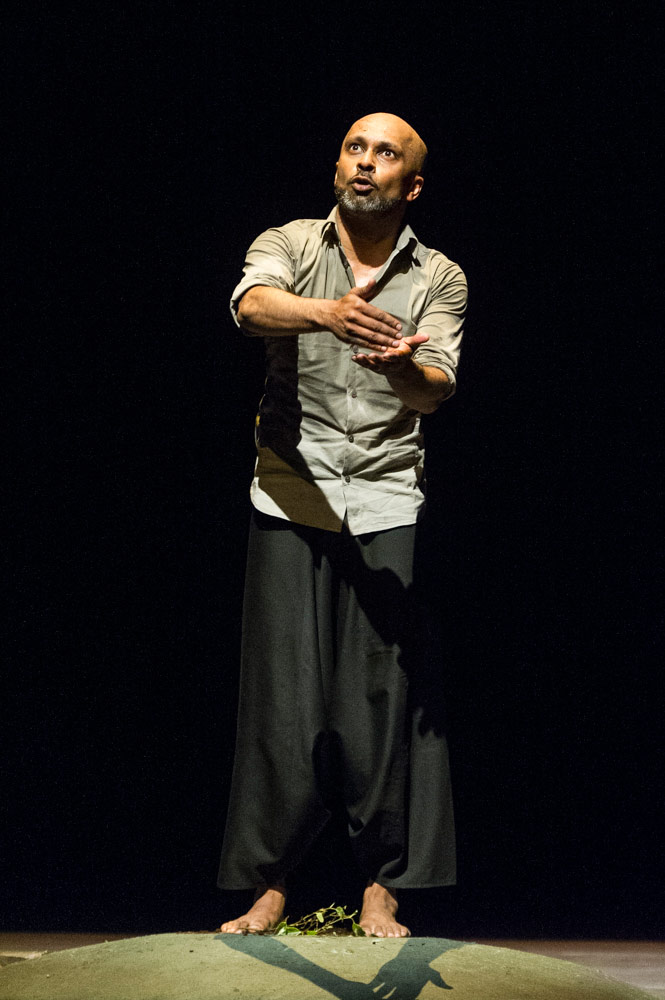

Khan picks up on the closing words of one of the speakers about religion for his epilogue. No longer silent as a dancer, he performs his solo to the sound of his own voice as he moves about a deserted temple – in fact, The Grange at Northington, Hampshire, former home of an opera festival. The interior of the house is in a state of decay, though the cabalistic floor pattern of the interior temple is still intact. It serves as a sacred space for Khan’s reverie about being in the midst of a seismic change between the past and the suspended future.

A ghostly figure, he is seen struggling with himself between marble staircases offering different directions. He keeps saying ‘Stop’ between statements about looking back at the contentious past, until he concludes ‘Stop doesn’t necessarily mean stop. I would like to believe it just means pause.’ He stands poised on top of a balustrade, a blank doorway behind him as the film ends. I would like to believe that he is recharging himself for the next 20 years, drawing on his past while reinventing his voice and his company’s future.

You must be logged in to post a comment.