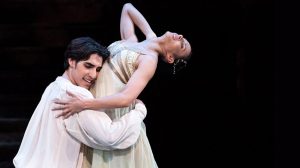

© Andrej Uspenski. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

Romeo and Juliet

★★★★✰

London, Royal Opera House

10 January 2022

Live performances from 10 Jan – 25 Feb 2022

Cinema relay 14 February 2022

www.roh.org.uk

At the start of the Royal Ballet’s second run of Romeo and Juliet, artistic director Kevin O’Hare came in front of the curtain to account for the challenges Covid infections pose for schedules and casting. Natalia Osipova and Reece Clarke as Juliet and Romeo had to make way for Marianela Nunez and Federico Bonelli, with Marcelino Sambé as Mercutio and Téo Dubreuil as Benvolio. Monday’s rival factions of Verona appeared to be in fine form and rude health (apart from the high death toll in the Act I marketplace brawl).

Bonelli, still remarkably boyish, makes Romeo a gentle dreamer, more interested in tuning his mandolin than cavorting with the town’s ladies of loose morals – though Hannah Grennell’s feisty harlot can stir him into action before he falls for Juliet. He’s not a show-off, unlike his mates: he dances to express his feelings rather than to impress. His solo to attract Juliet’s attention in the ballroom scene is sincere, if subdued. He’s so swiftly besotted with her that he’s almost stunned into responding to her impulsiveness. His partnering is unobtrusive, enabling Nunez’s Juliet to make the running.

She is eager for adventure from the moment we see her introduced to Paris as her prospective husband. Tomas Mock is an amiable, entitled nobleman, probably rich and a bit dim – just the sort of son-in-law socially ambitious parents would want. Nunez’s headstrong Juliet is intrigued by him, enjoying her formal coming-out dance with him in the ballroom. Then she encounters Romeo and her body language changes. She starts to relish the experience of being in love, undeterred by discovering he comes from a rival clan. She’s not naïve, as are some Juliets: she knows what she wants.

© Andrej Uspenski. (Click image for larger version)

At the start of the balcony scene, she boldly puts Romeo’s hand on her heart. By the end of the long pas de deux, its phases growing in intensity, she is ready to succumb whole-heartedly to his kiss. After their wedding night, she goes from frozen to frantic in her grief that he must leave her. They cleave together so naturally that the extravagance of the choreography, with its wild lifts and catches, hardly seems remarkable. Once he has gone, Juliet dances no more, until she is briefly forced to by Paris, at her father’s insistence.

Nunez’s Juliet has a more nuanced relationship with Mock’s Paris than is usual In Act III of the ballet. She seems to appreciate that it’s not his fault his pride is wounded, but her physical distaste at his touch overwhelms her. She goes into a kind of trance to block out his presence until she is obliged to agree to go through with their marriage. Nunez is more resolute than some Juliets in making up her mind to seek help from Friar Laurence, numbed though she is while Prokofiev’s music surges around her.

When she confronts the necessity to drink the potion, Nunez chooses to stylise her reactions of fear and disgust, reacting balletically rather than aiming for realism. Her Juliet is consistent, never ungainly, flatfooted or ugly, even when Romeo lugs her about in the final scene. Her agony at finding that he has killed himself just before she awakens on her bier is tragic, abjuring pathos as she joins him in death. It’s very much her interpretation of the role as a mature dancer, convincing though she is as an adolescent Juliet.

© Andrej Uspenski. (Click image for larger version)

Sambé dies a nasty death as Mercutio, enraged at being stabbed in the back by Ryoichi Hirano’s psychopathic Tybalt. Mercutio has been insolently provocative, taunting Tybalt in the ballroom as well as on the streets of Verona. Though Sambé confounded him as a virtuoso dancer and swordsman, he didn’t deserve to die in such a dishonourable fashion. Hirano briefly acknowledges that he made a bad mistake, stumbling into Mercutio while his back was turned, but nevertheless attacks Romeo as his friend’s avenger. Hirano’s Tybalt is a menace from the start, feared by the locals for his fiery temper. Clearly the worse for drink, his face sharpens viciously as he rampages into the revelry in Act II, looking for trouble.

There were fine supporting performances from Dubreuil’s fun-loving Benvolio, Kristen McNally’s protective Nurse and the acrobatic Mandolin sextet, buoyantly led by Joonhyuk Jun. The tumblers were accompanied by mandolin players in a box by the side of the side of the stage, while the orchestra players in the pit readied themselves for the dramatic climaxes to come. They sounded underpowered, with the brass section even more discordant than ever. Under the baton of Alondra de la Parra, the orchestra seemed to be following the dancers, who often started before the music, rather than driving the action. Pandemic complications have affected everyone involved in performances and productions. They pull together in difficult conditions to make a show happen as well as possible, for which we applaud them with grateful pleasure.

You must be logged in to post a comment.