© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

American Ballet Theatre

Swan Lake

New York, Metropolitan Opera House

20, 21 June 2013

www.abt.org

Of Swans and Princes

Say what one will about the relevance of the nineteenth-century ballets – and the quality of individual productions – it is an inalienable truth that every ballet dancer – all right, almost every ballet dancer – is dying to cut his or her teeth on Swan Lake. Along with Giselle and maybe Sleeping Beauty (though in actual fact most normal people couldn’t care less about Sleeping Beauty), Swan Lake is the very essence of what we think about when we think about ballet: epic, radically stylized, overflowing with powerful but enigmatic emotions. The choreography, especially what is left of Petipa and Ivanov, is a virtual primer of the glories of ballet esthetics: the expressive arms, the illusion of flight, the hairpin precision, the feats of technical mastery, the heroic, heart-on-the-sleeve leaps into oblivion. One feels the same sense of wonder watching Prince Siegfried draw an elegant arc through the air as one does seeing a star shoot across the night sky. Perhaps more so, because the wonder is sustained by the surging power of Tchaikovsky’s incomparable score. If ever there was a composer who understood the epic emotion, it was Tchaikovsky.

Which is not to say that every Swan Lake is created equal, or that all casts seize the heart in the same way. American Ballet Theatre’s 2000 staging, by Kevin McKenzie, is unsatisfying in several aspects. The dances in the first act are rather listless, made worse by sluggish, undancerly tempi. Many of the steps, especially in the first waltz, lag insistently behind the beat. The national dances in Act III are uninspired, a wasted opportunity. (Anyone who thinks character dances have to be a dull exercise should go see Balanchine’s Cortège Hongrois.) Von Rothbart’s gogo-booted alter-ego in purple spandex – a McKenzie creation – is a faintly ridiculous, though admittedly fun, addition to the third act ballroom scene. Hardest to swallow is the gutting of the final lakeside act. We go from ballroom drama to swan dive in no time at all, missing out on a whole series of kaleidoscopic corps-de-ballet dances. But the production has some redeeming qualities as well, starting with the painterly sets and sumptuous costumes (the swan tutus are particularly attractive, and not too swan-ish) by Zack Brown. The tiny parallel bourrée steps with which the swans make their first entrance are also a lovely touch – they manage to evoke the gliding flight of a skein of birds more vividly than the usual bounding jumps. Then there is the lovely motif of wrists wilting decoratively to one side, introduced by the courtiers in the first scene and then taken up by the swan maidens. Considering some of the Swan Lakes that regularly come through town – and the color-coded dripped-paint version performed across the plaza at City Ballet, it is useful to remember that things could be worse.

As usual this week, there was an impossible variety of casts to choose from, from Polina Semionova and David Hallberg on Monday to Veronika Part and Cory Stearns on Tuesday and Hee Seo (a début) and Marcelo Gomes at the Wednesday matinée. I was curious to see two débuts in the role of Siegfried: James Whiteside on June 20 and Herman Cornejo on June 21. Whiteside, a new soloist imported from Boston, was paired with Gillian Murphy, an old hand at the dual role of Odette and Odile. Cornejo, originally scheduled to dance with Alina Cojocaru – recently of the Royal Ballet – was duly supplied with a new partner, Maria Kochetkova from the San Francisco Ballet. The great challenge of Cornejo’s career has been finding a partner who is both well suited to his small stature and can also match his refinement, soulfulness, and musicality. Cornejo dances with a stirring mixture of purity and heroic ardor – he is princely by nature – and it has been difficult to locate a petite ballerina with the same kind of presence who can also match him for technique. It’s not a matter of size per se, but rather a question of reduced options.

© Leena Hassan. (Click image for larger version)

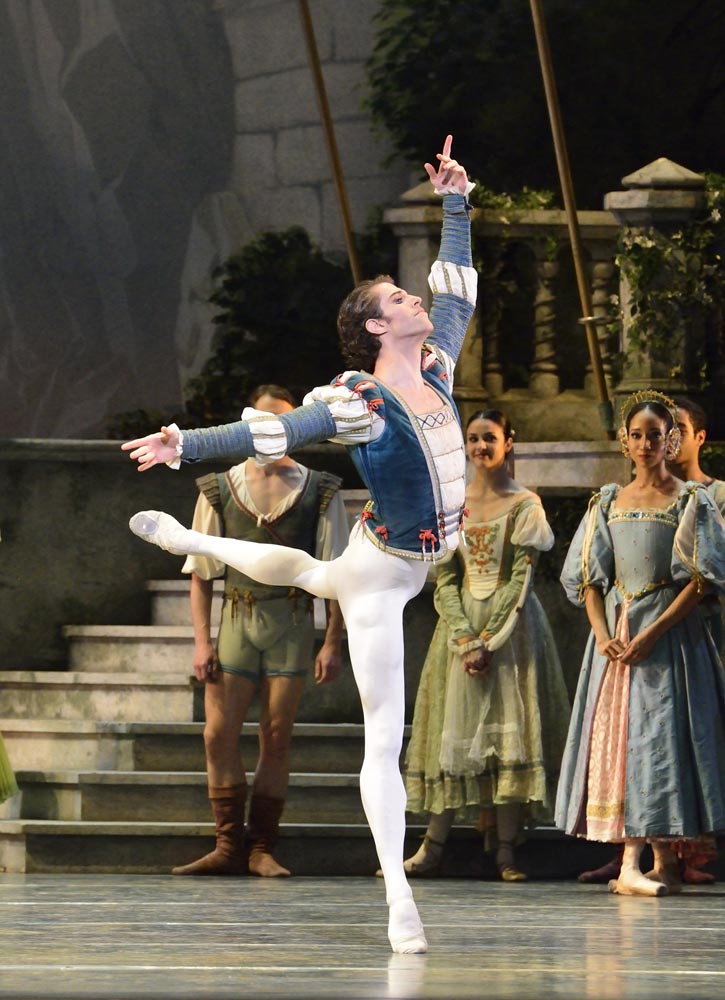

This conundrum had unjustly kept him from the role of Siegfried until the current season. He is in the flower of his career, and it was clear from his first steps on the stage that he was more than ready. In fact, it was as if he had been dancing Swan Lake all his life. In the first scene, he flirted boyishly with one of courtiers (Luciana Paris), kissed her hand with budding ardor as if wondering, “could she be the one?” Just as clearly, one could read the disappointment in his eyes. His first-act meditation solo, full of aching arabesques and slow swivels with one leg curving behind him (renversés), was delivered as one long thought: “where is my true love? How will I find her?” Cornejo was completely engaged in the story, down to its smallest details, as when, in the first lakeside act, he momentarily turned away from Odette to gaze at the other swan maidens: “where am I?” he seemed to be thinking, “what are these magical creatures?” One of the most impressive aspects of his dancing is the way each step is woven into the music and becomes a conversation with the other characters and the audience, an expression of his thoughts and emotions. This makes the technical feats – like his wondrous grand jetés en attitude, high, soaring leaps with the back leg in a beautiful curve – all the more impressive. His turns have lately become turbo-charged as well; with almost no visible preparation, he’s off. One can feel the momentum of the leg slicing through the air, and the effect of the body spinning in perfect balance, head erect, shoulders calm, chest open, face ecstatic. He lets the music carry him so that what you see is not technique but pure expression. Yes, my friends, this is why we go to the ballet.

And what of Kochetkova? Physically, she and Cornejo are perfectly matched. She is slight, almost wiry, with sharp features and long limbs. And strong. Clearly, she has thought about the role, shaped it, laced it with tasteful and intelligent detail: a little ripple through the head and shoulders here, a quick, nervous bourrée there, and deep, expressive backbends, all carefully coordinated with the music. She has worked it all out, and shaped the aspects of Odette (feverish, impulsive) and Odile (hard, manipulative) to her own body and temperament. The results are impressive. There was not a single challenge that she did not meet with great aplomb (including the fouetté turns, which she peppered with double pirouettes). But as yet there’s not much depth (or risk) to her interpretation, or a definitive stamp. At times, there was a glimmer of something stirring within, a deeper connection with her partner perhaps, but only for a moment. Her musicality is correct but not very incisive. For now, Cornejo will have to burn for the two of them, as he did last night, turning the ballet into Siegfried’s story, and Odette and Odile into creations of his imagination.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

The previous night had been dominated by Gillian Murphy’s performance. She is an absolute powerhouse in this role, a kind of super-stylized, inhuman creature, an art-deco distillation of speed and daring. She downplays the interpretative details, giving us unadorned movement, which becomes, on its own, hyper-dramatic, epic. Not for her the limp fin-de-siècle lines. Her head is proud, her arms as creamy-smooth as moonbeams. As Odette, she is otherworldly; as Odile, a glamorous, glittering ineluctable force, swooping around her partner head first, without fear. Her technique is strong as ever: effortless, powerful turns, fast or slow; a lush rolling down from pointe; radiant balances. And there is something deeply American, sleek and unmannered, about her dancing. She’s like a ballerina imagined by The Great Gatsby, a dancer of the future.

Next to her, James Whiteside seemed rather less at ease. Watching him perform a pure classical role for the first time, one notices several things. A certain lack of finesse in the lines created by his body, hard landings, and some discomfort in the slow, legato passages. Swan Lake does not offer many fast steps – his specialty – in which to show off quick-footedness and wit. Added to that, the princely mode doesn’t seem to suit his temperament. He’s not a natural, but he’ll doubtless improve. Already, he looked more at ease in the partnering sequences.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

On both nights, the swans made a strong impression with their vivid, dynamic dancing. There were other highlights as well: the crisply synchronized cygnets, the freedom and playfulness exhibited by Devon Teuscher and Christine Shevchenko in the pas de trois on June 20th, Jared Matthews’ gleeful rendition of the purple seducer – Von Rothbart – on June 21. Matthews, once so timid, is finally coming into his own, trusting himself to do more than get through the bravura steps. Then there was Martine Van Hamel’s empathetic rendition of the Queen, more worried about the possible causes of her son’s loneliness than insistent that he should pick a bride. Add to that an excellent violin soloist on June 20th. And a few low points, like the consistently flat violinist on June 21st. And what to make of Ivan Vasiliev’s Von Rothbart? Vasiliev plays the role straight, which renders it even more funny and preposterous. As he approached each of the princesses in the ballroom and yanked her out of the way unceremoniously, he seemed to be gathering strength for one last gasp-inducing jump-that-has-no-name: a sort of split, half-circle, gliding number that took off like a zeppelin and landed halfway across the stage. Well why not, after all?

You must be logged in to post a comment.