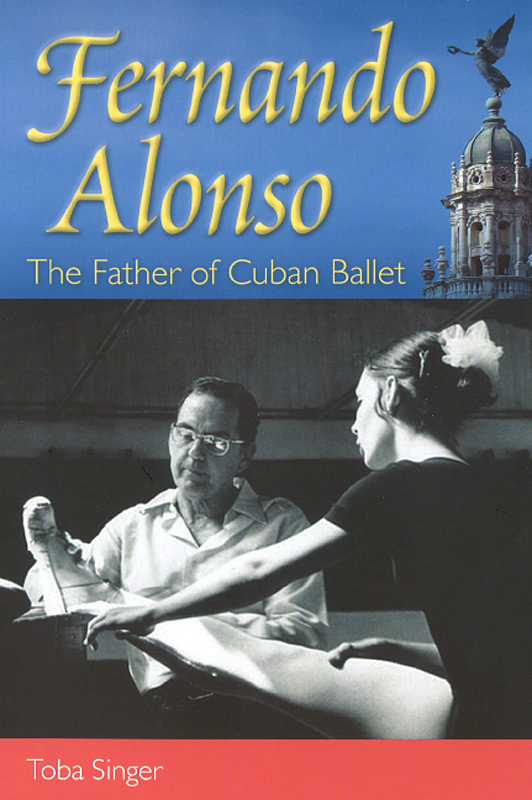

© University Press of Florida. (Click image for larger version)

Fernando Alonso: The Father of Cuban Ballet

By Toba Singer, www.tobasinger.com

University Press of Florida

ISBN: 978-0813044026

Publishers page on Fernando Alonso, The Father Of Cuban Ballet

Interview with Toba Singer

Think Cuba, think ballet. Think Cuban Ballet, and the name that comes to mind immediately is Alonso – Alicia Alonso, long acknowledged as the founding mother and prima ballerina assoluta of the National Ballet of Cuba.

But there’s another Alonso whose name is also synonymous with the establishment of classical ballet on the sultry alligator-shaped island in the Caribbean, and also with being the driving force for its acclaimed development and continuation. He is Fernando Alonso, who has worked tirelessly for nearly seven decades to perfect and share his knowledge of this art with countless young dancers, many of whom have reached world-class status. Yet very little has been written about him – until now.

© Toba Singer. (Click image for larger version)

In 2014, Fernando Alonso will be 100 years old, and he still has a twinkle in his eye and a great sense of humour. Ten years ago at his 90th birthday celebration he stated in an interview: “There are three things that will never change: my love for women, admiration for the art of the dance, and my dedication and love for my country. These will never change.” And reading his life story, he has been true to his word. Born with the longest name imaginable – Fernando Juan Evangelista Eugenio de Jesus Alonso Rayneri – he was a romantic thinker, wanting a scientific solution to everything. He was brought up in a house filled with music. His mother was a pianist and later president of Havana’s Pro Arte Musical which brought the young boy into contact with some of Cuba’s and the world’s great musicians. He also loved using his knowledge of science to observe nature – he was a bird breeder and, through crossbreeding, created a red canary – and he once spent eleven days exploring caves and marvelling at internal waterfalls and rivers. It was his younger brother Alberto who first started ballet classes to make him a better footballer. Soon Fernando joined him, and stayed, especially since there were 126 girls to six boys, and one of those young girls was the pretty star pupil, Alicia Martinez. The two soon fell in love.

© University Press of Florida.

In 1937, Fernando, seven years her senior, went to America to look for work and Alicia, at the tender age of 16, joined him. They got married and a year later their daughter Laura was born. In New York, the couple danced continuously, first in musicals, then with some of the biggest names in the international dance world of that era, all the while taking classes with famous teachers. Watching Alicia in class, Fernando would study the different teaching practises of the different teachers, and took the best parts of each system to develop them, from a scientific foundation, into the basis of his own Cuban-flavoured pedagogical studies. The couple danced all over the world together and were members of Ballet Theatre for eight years. But they remained patriotic to Cuba and returned home permanently in 1948 when Ballet Theatre found itself facing a major financial crisis. The desire to form their own company was financially challenging with many bills promised ‘manana’ and once, when the money ran out, an ad was placed in a newspaper for a sponsor. A response came from La Polar brewery, which agreed to pay for one performance providing there were some (advertising) ‘bears’ on stage! .’ We told them we’d put bears on the stage, beer bottles, whatever they wanted,” reported a member of the University Student Federation of Havana, which had pledged to support the company. The Ballet Alicia Alonso persevered and, filled with dancers from Ballet Theatre, won acclaim on its tours of Central and South America. It was at this point that Fernando, while still performing, decided to change direction and dedicate himself to the needs of the company by becoming its director. However dark days lay ahead for them all. During the Batista regime the company was disbanded for three and a half years and not reinstated until the revolution of 1959 .

In 1950 Fernando had claimed another milestone, that of founding the Alicia Alonso Academy of Ballet with the understanding that here, native Cubans could be trained in the art of classical ballet, and be a permanent source for the company. So it was on this project that all attention was focused during the years when the company did not function. With Fernando as teacher-director, all three Alonsos worked tirelessly in establishing an academy, which would, and still does, rival any of the top quality international ballet schools of today.

Much was miraculously achieved despite the troubled political and economic times, but the 1959 revolution brought great changes to the island – including the re-establishment of the ballet company. There is an interesting anecdote about how it received funding that was told to me by Alicia Alonso about herself. However, here in the book, Fernando now claims the same story. As he tells it, one night, after mounting a gala in celebration of the revolution, Fernando was surprised to be disturbed around midnight by an acquaintance who walked into his bedroom accompanied by the new revolutionary dictator, Fidel Castro himself. The three of them talked politics for nearly three hours and on leaving, Castro asked Fernando how much he needed to reorganize the ballet company. Fernando tossed out a sum that he felt was somewhat over-ambitious. ‘One hundred thousand pesos a year’ he replied anxiously. ’We’ll give you two hundred thousand, but you have to guarantee that it will be a good company’, was Castro’s response. It has turned out to be money well spent. However, Fernando claims in this book that Castro’s direct manner in asking him, not Alicia as she claims, showed that he, Fernando, had been entrusted with the restructuring of the national ballet company, with the help of both Alicia and Alberto – another fact that has been reported differently down the years. One fact agreed by all is that that Fidel Castro has been a constant support of the Cuban Ballet.

© University Press of Florida. (Click image for larger version)

The newly formed company took ballet out of Havana’s theatres into the villages and countryside, dancing in factories, schools, hospitals etc, and thus creating a dedicated following. A great bond was forged with the Cuban people, and still evident today is the country’s love and pride in its classical ballet heritage. The Revolution brought more hardships to the country including a blockade and trade embargo. The interruption of tours overseas for five years resulted in a lack of foreign income as well as the disappointment of not showing to the outside world the company’s high standards. When the country was plunged to the brink of war in October 1962 with the Cuban Missile crisis between the US and Soviet Union, the company continued to dance for the people, despite the fear of possible annihilation at any point.

Fernando continued to work with the company and establish the smooth running of the school in the capital until his divorce from Alicia in 1975 when, after dancers took sides, it seemed best for him to go to another city to live. This was Camaguey, where he settled down with a new wife and took over the running of another excellent company and school. When questioned why Cuban dancers are so outstanding in technique and artistry, he stated that the success can be found ‘in the presence of a ballet school with a pedagogical system, scientifically constituted, which bears the seal of the fully profoundly classical style.”

He has proved himself by the outstanding results over the years. Many of his pupils are internationally known and acclaimed and they – among them, Loipa Araujo, Aurora Bosch, Carlos Acosta, Ramona de Saa, Lazaro and Yoel Carreno, and Lorena and Lorna Feijo – add their own comments in seventy pages of short interviews, giving more insight into this remarkable man. There are fifteen pages of flat, black and white photos that show the handsome Fernando from his early years as a dancer to coaching young students well into his nineties.

This book serves as a timely tribute to an incredible man whose vision and dedication to his art has established one of the world’s finest classical ballet systems. It also finally and firmly establishes Fernando Alonso in his rightful place in historical annals as one of the world’s greatest ballet teachers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.