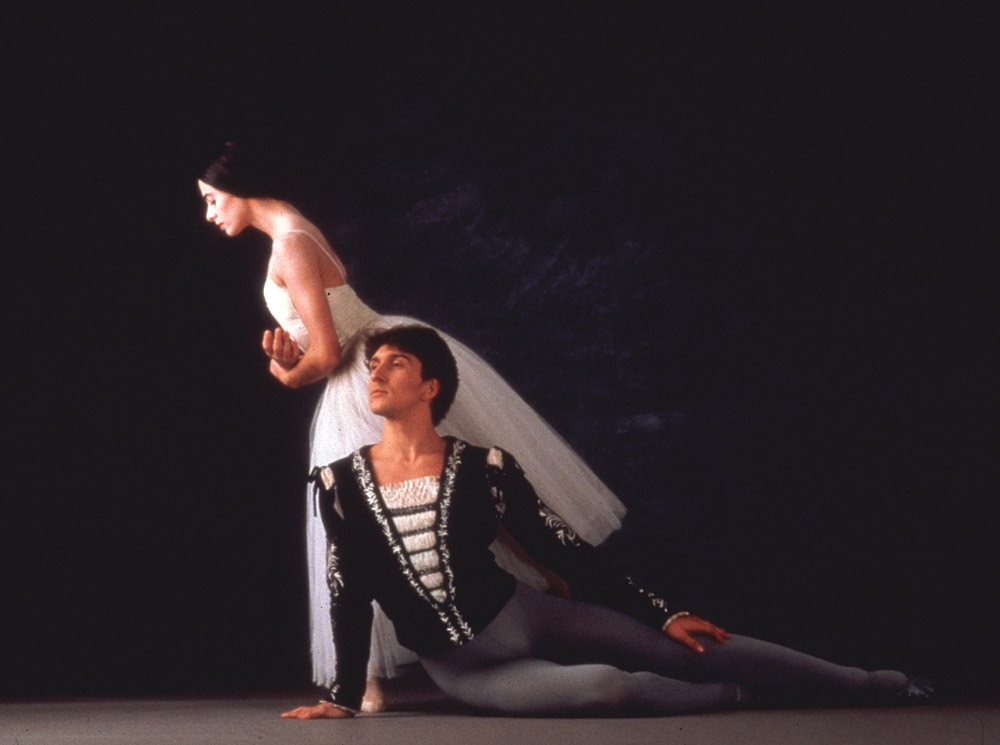

© Leo Barizzoni. (Click image for larger version)

www.juliobocca.com

www.balletnacionalsodre.gub.uy

A New Life – Julio Bocca in Montevideo

After his final dance at the Metropolitan Opera House in the summer of 2006, Bocca stood before the cheering, tear-stained crowd and waved goodbye. The performance had been of MacMillan’s Manon opposite Alessandra Ferri with American Ballet Theatre. Bathed in sweat, hair matted, Bocca looked exhausted, overcome and elated. Someone handed him a bottle of beer. He stared out into the hall, taking in the waves of affection with a sheepish grin. He seemed to make the transition from dancer to vulnerable mortal – albeit significantly more handsome than the average – in the blink of an eye.

A year later he bade farewell a second time, more definitively, in a free outdoor performance at the foot of the Obelisco in Buenos Aires, his home town, smack in the middle of the city’s widest avenue, the 9 de Julio. Three hundred thousand fans showed up. There were fireworks. Then it was over. The inevitable questions began to float around him. Where would he go? What would he do? Would he be offered the directorship of Argentina’s storied ballet company, where he had gotten his start? At first, he disappeared from view. He moved to Uruguay, a tiny country across the Río de la Plata from Argentina known for its affable population and beautiful beaches. Two years later, in 2010, when he re-emerged from his self-imposed retreat – he is famously shy off-stage, despite his onstage ardor – it was to announce that he had been asked to direct Uruguay’s national company, the Ballet Nacional SODRE. He’s been there ever since.

© Jack Mitchell, courtesy ABT. (Click image for larger version)

On a recent trip to Argentina, I took the Buquebus boat over to Montevideo to talk to Bocca about the last five years. The city is sleepy, but inside SODRE’s beautiful new building things were humming. The studios are inviting, with wood-lined walls and plentiful windows allowing in the surprisingly bright winter sun. The offices are pleasant, cheerful. People are constantly popping in with questions, decisions to be made. Later in the day, Bocca sat down to watch a rehearsal of a work-in-process by Demis Volpi, a young Argentine-born choreographer now in residence at Stuttgart Ballet. The ballet had its premiere on August 13, as part of a mixed bill that also included two works by Uruguayan choreographers. Maria Riccetto, the Uruguayan-born former ABT soloist whom Bocca lured back home in 2012, was the lead.

Earlier, in his office, Bocca reflected on his new life in Uruguay, his plans for the company and his larger thoughts about ballet in Latin America. The following is a slightly edited and translated version of our conversation.

Why did you move to Uruguay?

When I retired from dancing at the end of 2007, I needed a place where I could have some peace. Where I could go out, go to the supermarket, and have a normal life. In Argentina that was impossible. People stopped me in the street to ask for pictures or an autograph. I wanted to be somewhere where there were fewer people. Uruguay has that: there aren’t too many people. And it’s close to Buenos Aires. If I need some excitement, I just hop on a boat for a visit. I found I liked it here. I met my partner [an Uruguayan economist] and that allowed me to experience life in a different way. I settled down. I love the proximity to the water. When I was a kid we used to spend our holidays at Mar de Ajó, a beach near Buenos Aires. My apartment has a view of the water. And Montevideo is only an hour from the beach, from Punta del Este; we can go on the weekends. And then, two years later I was offered the opportunity to direct the company.

© Ballet Nacional del Sodre.

What did you do when you first moved to Montevideo?

I spent two years not doing anything. I remember when I did my final outdoor performance on the Avenida 9 de Julio, in front of 300,000 people. I went back to my apartment and suddenly I was alone. It really hit me. I opened the door and…silence. It made me think. So for a while I did nothing, I disconnected. And then, gradually, I felt the need to get back in the game. I felt young enough to try new things, and the desire to pass on what I knew. I was always getting offers to do masterclasses and serve on juries. I gave a masterclass in Prague, and then they called me from Moscow, and then from a competition in New York, and I started to get back into it. After all the work I had put in, I felt a need to find my place, not to cede it to someone else. Then the opportunity to lead the Ballet Nacional SODRE arose.

How long have you been with SODRE?

I took over the company five years ago this June. We’ve accomplished a lot in that time. When I arrived, this – he points at the walls of his office – didn’t exist. The basic structure of the theatre was there, but the rest, the offices, studios and dressing rooms, weren’t yet finished. SODRE has been around for eighty-six years, but its old headquarters were destroyed in a fire in 1971 and it took forty years to rebuild. The organization [Servicio Oficial de Difusión Radio Eléctrica] includes a chorus, the national symphony orchestra, a youth orchestra, a chamber orchestra and the ballet. The building also houses workshops where we build costumes, sets, wigs, drops, everything.

Did you accept the job right away?

Yes, because it was a challenge. The challenge was to start from scratch. Everything had to be built from the ground up.

When did the new building open?

It was inaugurated in 2009. All our shows are held here; the house seats 2000. It’s a beautiful, warm theatre with good sight lines and nice dimensions.

© Santiago Barreiro. (Click image for larger version)

What is the public for ballet in Uruguay?

It’s growing little by little. The biggest houses are for the classical ballets. I’m introducing 20th and 21st century chorographers little by little. In 2013 we did a gala with works by William Forsythe, Jiri Kylian, and the Argentine choreographer, Oscar Aráiz. Right now, Demis Volpi is setting a work on the company. That will premiere on a program that includes works by Martín Inthamoussú [a Uruguayan choreographer] and Andrea Salazar, a former member of the company. For the latter, we’re using music by Luciano Supervil and Juan Campo Donico, two members of the Uruguayan-Argentine electro-tango group, Bajo Fondo. That’s for this August. The idea is to develop our own repertory. Every year we do four programs, one contemporary program and three classical ballets. We’re always full. This year, we sold a record 25,000 tickets for Giselle.

Is there a strong tradition of ballet in Uruguay?

The Uruguayan public is very cultured. Ballet had languished a bit but we’re bringing the audience back. There’s an audience of habitués but also a new audience. We tour a lot, and the idea we’re trying to create is that ballet is for everyone. This is a national company, and our mission is to bring culture to the people. We get a lot of young people in the audience, which is good.

© Anthony Crickmay, courtesy ABT. (Click image for larger version)

What state was the company in when you arrived?

It had suffered a lot. After the fire it didn’t have its own physical space. It had to rehearse and perform in different places around town. When I arrived, they were rehearsing in the Palacio Salvo – a famous Beaux-Arts building downtown. But because of the bureaucratic way it was run, there was almost no publicity. Maybe an ad would come out the day of the last show. And the quality of the dancing was not great. There would be shows with 5 people in the audience. They tried to do classical works but it was impossible; they didn’t have enough dancers. So they did excerpts and some contemporary works. There were no auditions, and no young people coming in. The year before I came in there were something like five directors.

How were you able to change things around?

When they called me, I made very clear what my way of working would be. I was at ABT for twenty years and I have a more American, private-enterprise kind of mentality. I told them I needed to have more work hours and annual contracts with auditions every year. A more normal situation. I wanted to bring to bear my experience of working with many different choreographers and dancers. And to develop the company so that Latin America would have another important classical company. There was a first meeting with the dancers where I laid out my ideas, my plans for change. I told them it was up to them. Some accepted my terms, others didn’t and moved on. I held the first auditions in May of 2010. And on June 1 we went to work. In November I held another audition, planned further ahead so more people could show up.

© Santiago Barreiro. (Click image for larger version)

Where do your dancers come from?

Fifty percent are Uruguayan. We have a national school. When I arrived it was in bad shape. Two years ago we began to change the format. The first few years I wasn’t able to take anyone from the school. It’s independent from the company but I try to help. We brought in ABT-certified trainers to train the teachers at the company, and invited a teacher from each province in Uruguay to take the certification course. That way everyone will have the same base.

And the other fifty percent?

I have dancers from Australia, Spain, Venezuela, Brazil, Paraguay, Perú, Argentina, and soon Japan. Most of them come to audition here. A few send videos and we take them for a three-month trial period.

How has the company changed since then?

Every year the level improves. Now it really feels like company. It’s very young; most of the dancers are between 18 and 24. I have eight or nine older dancers who stayed on from before, and they have an important role to play as well.

What were those first days like?

At first, some of the veterans just looked at me. I could tell they were thinking: “every director comes in here and says he’s going to change things, but it’s too hard.” Then we got down to work. That year we did Giselle, a mixed bill – Nuestros Valses and Doble Corchea by Vicente Nebrada and Raymonda suite – and Swan Lake. All of that in six months. The audiences were incredible. The Colón Theatre lent us the sets for Giselle and Swan Lake because we didn’t have anything. At first we didn’t even have heat in most of the building; it was freezing in here. The dancers rehearsed in a studio below ground because it was the only place that had heat.

© Santiago Barreiro. (Click image for larger version)

Like Soviet times….

More or less (laughs). The company manager, Gerardo Bugarin, and I moved into the building before the offices were even ready. He brought in a table, and we used our own computers. There was no light, nothing. It was so cold! As soon as the dressing rooms were usable, we told the dancers to move in. We felt that if we took possession of the building we would be able to push for things to be finished more quickly. First they finished the studios, and then the offices. Upstairs we have the physical therapy areas, and on the fourth and fifth floors, the dancers’ dressing rooms.

When was everything finished?

Two years ago.

How did you manage to get things moving against such odds?

The government backed me. And, the truth is, I can be an hinchapelotas [a pain in the ass] when I need to. From the start, I already had the year planned out, and the year after that. I had already spoken with all the choreographers, made a budget and had reached out to businesses for sponsorship. We have three state-run companies sponsoring us, and two private. It’s the first time the state has allowed a public-private partnership of this type in Uruguay. I think my name helped, the fact that people knew who I was and what I had accomplished. They trusted me. They saw what we managed to accomplish over the course of just six months.

© Leo Barizzoni. (Click image for larger version)

Were there any hiccups at the beginning?

The day we opened the mixed bill there was a nation-wide strike. But not all the unions joined in. In the theatre, the technicians and state employees joined the strike, but not the independent contractors. We went ahead with the show. I said, “if we can’t open, thank you very much, but I’m leaving.” I didn’t want to work that way, especially after spending six months rehearsing underground. We had made a promise to the public, we were trying to win them back. Part of the government backed me. The Minister of Culture came, some ministers, and the public. The unions stood outside, calling me names as the people came in. But the theatre was full. I handled the music from my computer; we used basic lighting. The curtain went up and we did the show. After that, there was a change. Someone had stood up to the unions to defend something different, the right to work.

Have there been further conflicts with the unions?

No. We’ve been able to manage things. I met with the main union leader and we’ve been able to move ahead. We’ve never had to cancel a show.

Why did you ask María Riccetto, your former colleague at ABT, to join the company?

I respect her as a dancer, she’s from here and I had the feeling she could bring a lot to the company and to new generations of Uruguayan dancers, so they could see that there was a place for them here. Before, if they went to the national academy they assumed they would have to go abroad to have a career. I also wanted them to see a model of professionalism, something that perhaps we’ve lost a little bit in our Latin-American countries.

© Marina Harss. (Click image for larger version)

Are you planning to stay with the company long-term?

A while longer, vamos. The contracts are annual. Before, it was a three-year contract, but I prefer now to go year by year. I’m already programming 2017 and thinking about 2018.

What are your favorite (and least favorite) parts of the job?

I love the programming and working with the dancers on details once ballets have been set. I don’t like to teach. I’ve always felt that a teacher should have a choreographer’s sensibility so the combinations will always be interesting, never the same. I don’t have that. It’s one of the things I’ve always known: I loved to dance, but I didn’t want to choreograph. Directing was always somewhere in the back of my mind. Coaching, I love. I’d like to spend even more time in the studio than I do.

What is your main goal now?

I want the company to tour even more and develop an international presence. I’m talking to the Joyce [in New York] about a visit, a single evening-length work. Bringing the whole company is impossible. We’re trying to organize performances at the Liceu in Barcelona and Teatro Canales in Madrid with the whole company for Dec.-Jan. 2016-2017. We went to Spain last year. We’ve been to Italy, Oman, Mexico, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Paraguay, Chile, Cuba. Now we’re heading to Thailand and Israel. The idea is for the company to position itself as the Latin American company. It upsets me that Latin America doesn’t have a company like ABT, the Paris Opera. We have excellent dancers all around the world. So why have we never been able to create a representative company? We need to show that there is culture here beyond football.

Were you ever tempted by the Colón Theatre, in Buenos Aires?

Before I was offered the job at SODRE, they offered me the job at the Colón. This was before Lidia Segni signed on. I gave them the same conditions I asked for here and they looked at me as if to say, “we can’t promise anything.”

Was it difficult to pass that up?

No. I was enjoying my time. Maybe I wasn’t ready to take on the responsibility. It wasn’t the right time. The truth is, I’m very happy here.

© Santiago Barreiro. (Click image for larger version)

What are some of the works you’ve introduced to the company?

Sara Nieto’s Giselle, Raúl Candal’s Swan Lake, Silvia Bazilis’s Nutcracker, Bazilis and Candal’s Don Quixote, Anna-Marie Holmes’ Le Corsaire, Mauricio Wainrot’s Messiah and Streetcar Named Desire, Oscar Araiz’s Rite of Spring, Jiri Kylian’s Sinfonietta and now Petite Mort, William Forsythe’s In the Middle, Tudor’s The Leaves are Fading, Balanchine’s Donizetti Variations, Vicente Nebrada’s Nuestros Valses, Doble Corchea, and Percusión para Seis Hombres, Ronald Hynd’s The Merry Widow, Makarova’s Bayadère, Boris Eifman’s Russian Hamlet, Enrique Martínez’s Coppélia, Tango y Candombe by Ana María Stekelman. This year we’re doing Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet. Next year, Marcia Haydee’s Carmen and John Cranko’s Onegin. That’s a very big deal. We’ll do a program with Petite Mort and a new work by Graciela Figueroa, a Uruguayan choreographer. Then, for 2017, I’m discussing putting on Études, Béjart’s Gaîté Parisienne, and Grigorovich’s Spartacus.

Why do you think there are so many great Argentine dancers around the world?

It’s a big country, and we have good teachers. I think also that because we had so many immigrants, our style is vary varied. But I think there are fewer now. The last was the generation of Herman Cornejo. I gave a class at the Colón school and was surprised by the level.

In a negative sense?

Yes, it seemed…. (pause)

Average?

Yes, very average. I know the school has been working in different spaces. [The school used to be based at the Colón Theater but has been working in temporary spaces since the theatre’s renovation, which officially ended in 2010.] Neither they nor we have a primary and secondary school for kids studying at the ballet academy. I think that would help, so the kids wouldn’t have to spend their days running from one place to another. We’re working on an idea for a school.

Why do you think the training was so good in your generation?

There were great teachers who came from abroad, Gloria Kazda and Wasil Tupin. It was a strong generation, many of them with links to the Ballets Russes. They, in turn trained a new generation of teachers, Mario Galizzi, Katy Gallo, and others.

© MIRA, courtesy ABT.

Do you miss dancing?

No. Not at all. Sometimes when I listen to a particular piece of music, like Romeo and Juliet, my body starts to move. It’s hard to see another person dance it. But from the beginning, I was all right. I stopped dancing in December, just before the holidays, and it just felt like the holidays never ended. The transition wasn’t so jarring. Sometimes I take a barre, mainly because I hate going to the gym. I have to keep an eye on mi pansita, my little belly.

[…] You’ll find the interview here. […]

El señor Julio Boca cambio el ballet en el Uruguay, porque realmente se impuso desde el primer momento a la burocracia y trabajó e hizo trabajar las horas necesarias para poder ser un ballet integrado por profesionales. Sinceramente fue tan grande el cambio que hubo en el cuerpo de baile, escenografias, vestuario, etc. etc. que el teatro empezo a tener una gran respuesta de publico que al dia de hoy ha llegado a vender en una obra de 20 a 25 mil personas. Increible y eso se logra con mucha disciplina, y trabajo.

MARIA RICHETTO una gran bailarina y super profesional.

FELICITACIONES

LINDO REPORTAJE