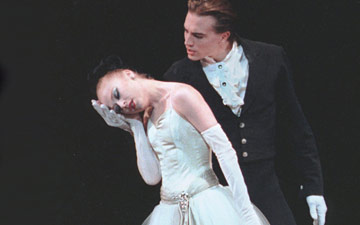

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

Miami City Ballet

The Fairy’s Kiss, Walpurgisnacht Ballet, Polyphonia

★★★★✰

Miami, Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts

10 Feb 2017

www.miamicityballet.org

www.arshtcenter.org

Sealed with a Kiss

The big event in Miami City Ballet’s Program Three, which premièred at the Adrienne Arsht Center in Miami on Feb. 10, was the opening of Alexei Ratmansky’s new version of the 1928 ballet The Fairy’s Kiss. The forty-five-minute work, based on Hans Christian Andersen’s enigmatic story “The Ice Maiden,” may not have been the only ballet on the program, but it was certainly most highly anticipated. What would the Russian-American choreographer do with this ballet that has bedeviled some of the greatest choreographers of the twentieth century, including Bronislava Nijinska (the original choreographer), George Balanchine and Frederick Ashton?

Nor was this Ratmansky’s first Kiss. He had already made two previous versions, one in Kiev, in 1994, the other for the Mariinsky, in 1998. (It was his first large-scale ballet.) He has said in interviews that he felt that neither was fully satisfactory. No version has stayed in the repertory for long. What is its secret? Some have argued that the problem is the ending: four minutes of quiet, un-dramatic music reminiscent of the end of Apollo. Stravinsky, who wrote the score for the dancer and impresario Ida Rubinstein, imagined the moment as a magical transition, the passage from the mortal world to a higher plane. But how does a choreographer show this through dance?

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

Stravinsky’s wove his score out of a dozen-or-so songs and piano pieces by Tchaikovsky, to whom the ballet was dedicated. In his mind, Tchaikovsky too had been “touched” by the muse, and suffered for it – he saw the ballet as an allegory. Originally the score was criticized as sentimental. But its main issue may actually be a lack of drive. The melodies are haunting and beautiful, but don’t build powerfully to a climax; they support the story but don’t push it forward.

The story, too is an enigma. Andersen’s tale is long and complex, weaving in themes from the author’s own life: the gift and burden of the hero’s wondrous talent, the power of ambition, the faithlessness of women. Rudy, the hero, is a striver, the son of an alpine hunter who loses his mother at a young age, falls in love with a rich miller’s daughter, and is finally captured by a fairy, the same fairy who saved him from death when he was an infant. The young man’s credo is that “nothing is so high that one may not reach it. You must climb on, and if you have confidence you won’t fall.” His boldness is his strength but also his ruin. At the moment of his greatest happiness, the fairy drags him down beneath the icy waters of a lake. It seems like a cruel, depressing end.

Stravinsky simplified the story to a skeleton with four scenes: The infant boy is saved from a snowstorm that kills his mother. The boy falls in love. The boy is seduced and tricked by the fairy. (As in Swan Lake, the hero is tricked into chosing the wrong girl.) She marks him with a kiss on the foot and then leads him away from his earthly bride to his destiny, a destiny greater even than love. Unsurprisingly, it is this scene that has given choreographers the most trouble. Balanchine put a net onstage, which the young man was forced to climb, grappling his way toward the fairy’s realm. Dissatisfied with this solution, he eventually dispensed with the plot and turned the ballet into a suite of dances culminating in an enigmatic solo in which the young man leaps and falls to the ground again and again, as if reaching for something beyond his grasp.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

Ratmansky seems to have suffered no such doubts about the ending. In fact, the last four minutes are the most transporting and transcendent moment in his ballet. After a wrenching scene in which the hero, danced by the ardent and unaffected Renan Cerdeiro, finds himself pulled between the domineering fairy (Simone Messmer) and the tender Jeanette Delgado (his bride), he gives in to his fate. As in Balanchine’s Serenade, both women embrace him; he loves both, but must give up one of them. Then, after the fairy plants her kiss, the scene changes. The corps returns, dressed in filmy tunics. One by one, they enter, tilting forward like the Shades in La Bayadère. The young man watches with rapt attention. They arrange themselves into rows; two dancers weave in and out, like Princess Aurora and Prince Désiré in the Vision Scene of Sleeping Beauty. Three women emerge from the group and shuffle forward together on pointe, like the Muses in Balanchine’s Apollo. The dancers drift in and out of sequences from one ballet after another: Les Sylphides, Les Noces, Giselle, Serenade. Sometimes the young man watches, and sometimes he directs, like a choreographer. Finally he is swept up in a complex formation that encompasses the whole stage, each dancer forming one small part of the whole. The final image is poetic, grand, inspiring. It takes one’s breath away.

And yet the ballet is, for the most part, understated, its lack of bombast echoed by somewhat drab sets and costumes by Jerôme Kaplan. There are two Cézanne-esque houses and a church at the back of the stage, and lattice-like projections by Wendall Harrington. It takes a while for the colors to heat up; the lighting, by James F. Ingalls, is a bit dim. This is especially true at the beginning of the ballet, which is also its weakest section. This should be a moment of high drama: a peasant woman struggles through a snowstorm, clutching a baby. A group of ice spirits dances around them. But the scene isn’t impactful enough; we don’t fear for the woman’s life or that of her child. The dances for the spirits seem disconnected from their fate.

After this slightly off-kilter beginning, the story takes off. Cerdeiro dances the role of the young man with freshness, hope, simplicity and crystalline technique. He and the bride (Delgado) share a raucous folk dance, full of quick, sharp, footwork. The women lift their skirts, stomp the floor. The men fall to their knees and jump with their ankles crossed in sharp, quick, rhythmic sautés. The villagers wear heeled shoes; a full half of the ballet is danced off-pointe, which makes the dancers look like people made of flesh and blood, not abstractions. The rapport between the two lovers is tender, sweet, human. They can’t keep their hands off each other and have to be continually pulled apart by their friends.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

Then comes the young man’s meeting with the fairy, now disguised as a gypsy. She reads his fortune and reminds him of his past. In the ballet’s most haunting moment, the opening scene is replayed in a flashback. The young man “sees” the death of his mother, clutching his head in horror. There follows a tender pas de deux with his bride (Delgado), and later, a more passionate one with the fairy (Messmer), now disguised by a veil. In between there is a dance for the bride and her bridesmaids, who lift and support her, sharing in her moment of happiness. And then, an extraordinary solo for the young man, in which each leap seems inflamed by love and the casual boldness of youth.

The ballet is rich and direct, and touchingly human. The lack of affectation with which the Miami City Ballet performs it magnifies its warmth. Perhaps what is missing is a darker note, a suggestion of pathos and loss, especially at the beginning. But the ending, with its exaltation of the timelessness of ballet and its history, is grand, poetic and profoundly moving.

The Fairy’s Kiss was performed at the end of a program that began with Balanchine’s Walpurgisnacht Ballet, a company première, followed by Christopher Wheeldon’s Polyphonia. The corps in Walpurgisnacht was strong and fleet and deeply musical; New York City Ballet could learn a thing or two from the way they use their upper bodies and eyes. The lead woman, Lauren Fadeley, danced well but lacked authority; her partner, Jovani Furlan, had verve but his partnering was a little jumpy. In the soloist role, Nathalia Arja was astoundingly light, fast, and charming; her jumps, even on pointe, shot straight up into the air, like popcorn, without weight or effort.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

Wheeldon’s leotard ballet Polyphonia was danced stylishly by its four couples, though one could argue that the four women – four brunettes of similar build – were not distinct enough from each other. Emily Bromberg and Renato Penteado captured the legato flow that is Wheeldon’s specialty, as well as the sense of mystery in the “Three Wedding Dances” pas de deux, a distant cousin of Frederick Ashton’s Monotones. György Ligeti’s music in this section, played gorgeously by Francisco Rennó, is reminiscent of Satie (another similarity with Monotones). The other Ligeti piano pieces evoke French Impressionist music, the waltz, the tango. Polyphonia, from 2001, is still one of Wheeldon’s best pieces, created in a spare idiom he has long since left behind.

The Miami City Ballet dancers bring all these works to life, switching easily, it seems, between styles. Their approach is modest and direct; they don’t impose themselves on the choreography. Perhaps they might impose just a bit more. Especially in The Fairy’s Kiss, their imaginations and personalities are an important part of the story. There is still much for them to explore here.

* Marina Harss is currently at work on a book about Alexei Ratmansky, for Farrar Straus and Giroux.

I find your comment upon the opening scene of the ballet curious. You write:

“This is especially true at the beginning of the ballet, which is also its weakest section. This should be a moment of high drama: a peasant woman struggles through a snowstorm, clutching a baby. A group of ice spirits dances around them. But the scene isn’t impactful enough; we don’t fear for the woman’s life or that of her child. The dances for the spirits seem disconnected from their fate.”

After reading this I thought, “Is it her place to decide what is and is not impactful enough this early on?” Surely enough the ballet continues:

“In the ballet’s most haunting moment, the opening scene is replayed in a flashback. The young man “sees” the death of his mother, clutching his head in horror.”

What I find bizarre is your lack of written connection between these two moments. The scenario when introduced to you is ‘not impactful enough’; upon same scenario being remembered you find it the ballet’s ‘most haunting scenario’. Clearly Ratmansky decided to illustrate post-traumatic stress syndrome. It is in the ‘re-living’ of a moment that we realize its true impact. I wish that your critical reflection had made connection of these parallel moments in its resolution.