© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

The Dante Project

★★★✰✰

London, Royal Opera House

14 October 2021

Gallery of pictures by Foteini Christofilopoulou

www.roh.org.uk

After all the hype, Wayne McGregor’s Dante Project turns out to be something of a disappointment –- as did Akram Khan’s Creature for English National Ballet. In both cases, ballets created before the pandemic have been finessed by their creators during the interim. Where Creature is pessimistic about mankind’s fate, The Dante Project hopes for a finer future, filled with joy and light. Both productions are bolstered with copious programme notes explaining the original stories’ relevance to today.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Dante’s Divine Comedy was inspired by Christian, specifically 14th century Catholic theology, which The Dante Project replaces with nebulous spirituality. What is sin, these days, and can it be purged? The sins and their punishments in Dante’s Inferno are specific, as are the gradations of the nine circles of hell. Virgil guides Dante downwards through each one, leading him upwards through Purgatory, where he is cleansed of his sins. With Beatrice as his mentor, Dante is able to ascend through the nine spheres of heaven. Far too much for a three-act ballet to accommodate.

Instead, the composer Thomas Adès has created his own vision of Dante’s pilgrimage, completing his score before McGregor started choreographing Inferno for its premiere in Los Angeles in 2019. McGregor follows Adès’s structure but not his tonality. There are jokes, extravaganzas and references in the music that McGregor overlooks. The choreography remains much the same throughout all three acts: generically balletic (the women are on pointe) with contemporary dance swoops, swirls and lunges. Unexpectedly, the tortures of the damned in Inferno have little of McGregor’s signature contortions and acrobatic writhings. They’re more like the varied divertissements in The Nutcracker, watched from the side by Gary Avis’s Virgil as Drosselmeyer, with Edward Watson as his protégé, Dante.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

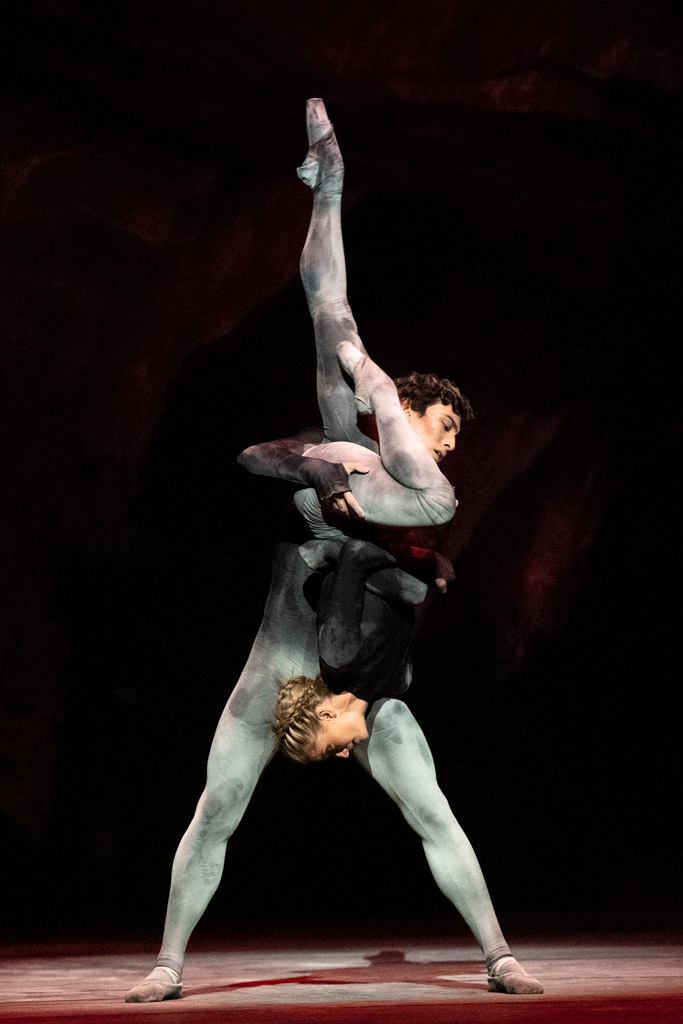

The sinners – maybe they represent all of us – are costumed alike in dark grey unitards, streaked with white chalk. There are no accessories to identify them, so it’s necessary to rely on cast lists and Adès’s partition in the programme of the 13 diverts in Inferno. Francesca Hayward and Matthew Ball are illicit lovers, buffeted together by infernal winds for eternity. They can’t be redeemed because they never cease to love each other in a poignant pas de deux. Calvin Richardson is an agonised Ulysses, borne aloft by waves and sea creatures in his endless voyaging. His is the most remarkable episode, unnamed in Adès’ score; McGregor has made his own choice of lost souls.

Anna Rose O’Sullivan’s Dido laments among a 15-strong group of svelte female suicides. The score invokes Liszt’s musical references to Dante: disconcertingly for a ballet audience, there are passages used in MacMillan’s Mayerling, with confusing connotations. Paul Kay and Joseph Sissens are soothsayers, back-to-back like Tweedledum and Tweedledee. James Hay is a vainglorious pope; Hannah Grenell, Melissa Hamilton, Meaghan Grace Hinkis and Mayara Magri are vengeful Furies or harpies enjoying their rampaging. Eleven men, cast as thieves, cavort to music resembling an Offfenbach operetta before plunging face down into the mire of the eighth circle of hell – though there’s no gradation of iniquity in this staging.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Tacita Dean’s set for Inferno is an upside-down mountain range reflected in a circular mirror above: a glimpse of a realm the sinners cannot attain. At the very bottom of the ninth circle resides Satan, immersed in an icy lake. Hell is frozen, not fiery. Dante, aided by Virgil and an angel in one of the poem’s last canticles, escapes by climbing up Satan’s body. In the ballet, Watson has a duet with Fumi Kaneko as Lucifer, who flees as the curtain falls on Act I. Since she wears a unitard like everyone else in Inferno, I’d mistaken her at first for Beatrice.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Inferno, a 50 minute Act I followed by a 30 minute interval, takes up half the ballet. It’s diverting but incoherent. We have no idea what Watson’s Dante has learnt from the random selection of sins, no matter how superlatively danced. There is none of the grotesque imagery in Gustave Doré’s illustrations, and the only Christian iconography appears to be in a section called Stations of the Cross, with ten figures wreathed in smoke.

Purgatorio, Act II, abandons Purgatory’s mountain of repentance to focus on Dante’s love for Beatrice. They had first met as youngsters, aged eight, and Dante had adored her from afar, while she was married to another man. He wrote a book of poems, La Vita Nuova, about his feelings for her, moving from courtly love to spiritual adulation. Act II of the ballet begins with Virgil carrying Beatrice’s dead body (she died at 25), as Dante recalls his encounters with her. Adès makes use of the recorded voice of a cantor in the Adès synagogue in Jerusalem to solemnise a parade of penitents. Pairs of youngsters then enact Beatrice and Dante’s early meetings, dressed in colour-coded costumes as they change places. Eventually, Sarah Lamb arrives as beatified Beatrice, taking over from Avis’s Virgil as Dante’s guide to Heaven.

Avis and Watson are kitted out by Tacita Dean in ill-fitting frocks with flounces and snoods. By Act II, Purgatorio, Watson’s turquoise number has become bi-coloured, the red top half presumably symbolising his earthly love or lust for Beatrice. Avis in yellow has become less pious, more human, as he dances a farewell duet with Watson before vanishing behind the set. Dean has provided an eerie street scene with an overpowering tree that glows purple as Watson dances an ecstatic pas de with Lamb, trying never to let go of her.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Act III, Paradiso, is McGregor’s Dance of the Blessed Spirits, a ballabile of celestial bodies to seraphic voices. Over a dozen principal dancers are on stage along with soloists, all costumed in silvery white unitards. They combine in multiple constellations on a blacked-out stage, while up above hangs a screen on which Dean projects mesmerising images of planets. In ballet heaven, the choreography would reflect the dance of the spheres in intricate patterns and scintillating enchainements of steps. McGregor is not that kind of choreographer, though the dancers make what they can of their surges of energy to Adès’s climactic music. Watson in a red robe embraces Lamb for the last time as he realises she is unattainable, far beyond his reach. The starry dancers evaporate as the music spirals into silence and a blast of white light dazzles the stage and audience.

The first night audience gave the production the inevitable standing ovation (necessary to see the large cast and collaborators take their bows and to note the absence of bouquets – this is an ensemble production). Watson was cheered for what will be one of his last performances since he retires later this year. Although The Dante Project is ostensibly built around his role as Dante, he is inevitably sidelined in the first and third acts, responding to the activity on stage and only occasionally taking part in it. He comes into his own in Purgatorio, Dante’s story of love for Beatrice as a human being and as his ideal. Lamb and Hayward (an early incarnation of Beatrice, as well as being Francesca da Rimini with Ball as Paolo) are suitably sublime in a saintly role. No passion is involved, which means that the allegorical spectacle is bound to be uninvolving. The narrative is fragmented, its relevance to a secular world far-fetched. Adès’s score, the production’s main virtue, can stand alone as concert piece, its homages to other composers less distracting than on a ballet stage.

You must be logged in to post a comment.