© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

Stravinsky/Balanchine – Black and White: Stravinsky Violin Concerto, Monumentum Pro Gesualdo, Movements for Piano and Orchestra, Duo Concertant, Symphony in Three Movements

New York, David H. Koch Theater

30 September 2012

www.nycballet.com

I’ve noticed two troubling trends this season at New York City Ballet. Perhaps they are connected. The first is the creeping tendency toward stolid tempi from the pit, especially under the baton of Clotilde Otranto. The other is a kind of disconnect in the way different types of ballets are performed. The more percussive, high-intensity Modernist works (like Symphony in Three Movements and Agon) are as lively and focused as I’ve ever seen them, perhaps even more so. The dancers, across the ranks, are attacking them with a kind of hunger, engaging with the music, the audience, and each other. The audience feels it, too – applause erupts here and there, in lapping waves. But this electricity does not extend to the whole repertory. This unevenness might have something to do with the absence of some of the more vivid dancers in the company – Jenifer Ringer, Jennie Somogyi, Ashley Bouder, Sara Mearns, to name just a few – who are out on leave or injured or coming back from an injury. Some of the more delicate, subtle works, the ones that require the most imagination and nuance, don’t quite add up. The poetry remains elusive.

Take Balanchine’s Apollo. Both of the young men who performed the ballet at the start of the season, Chase Finlay and Robert Fairchild, approached the role of the young god with great incisiveness. Each imprinted the role with his own physical qualities, imagination, and character. Even though, to my eye, one performance looked more finished than the other, I appreciated the differences between them. While each of them was dancing, the text of Apollo felt alive. But neither cast was fully satisfactory. The Muses were uneven; they seemed disconnected from each other and from the ballet. One saw steps, without a story. At other times, a kind of reverence got in the way of full-blooded dancing. Part of the problem originated in the pit: an overly emphatic interpretation of Stravinsky’s score divested it of its delicate wit, its radiant poetry. The ballet seemed to be slipping through the company’s fingers.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

The same has been true for other ballets, including Orpheus and Divertimento from ‘Le Baiser de la Fée (with the exception of the principals). The issue resurfaced in last week’s “Black and White” program of Balanchine/Stravinsky works (I saw the Sept. 20 performance), so named because all the ballets were performed in some form of rehearsal clothes. The opening section of the first ballet, Stravinsky Violin Concerto, composed of a series of playful, almost competitive quartets, was just too slow. The dancers were bogged down. It took a while for the ballet to snap into focus, and once it did, it was mainly due to Robert Fairchild, pushing it forward with his considerable energy. He led the boys on a mad dash about the stage, punching out the syncopated rhythms and launching himself into arrow-like jumps like a hellion, bent on getting his way. But he had little help from the orchestra.

The combative first pas de deux – each time I see it, it reminds me of those couples in which one partner wins every argument – was assigned to Maria Kowroski, as it often is. She has the right physique to make the most of its stretchy shapes, the deep arabesques penchées and extravagant backbend walk in her partner’s arms – weirdly similar to the one in Divertimento from Baiser – and, most of all, the famous spider crawl on all fours with which she encircles her partner/prey. All of these strange steps were effortlessly executed by Kowroski, but without much heat. The power dynamic, the way Balanchine has the woman utterly dominate the man – and it’s clear that this is about sex – simply didn’t register. It is not supposed to be an even match. (Sébastien Marcovici, Kowroski’s partner, is certainly passive enough to be convincingly outmatched, but doesn’t bring much else to the role.)

The second pas de deux fared much better, no surprise with Janie Taylor and Robert Fairchild in the leads. Taylor has perfected these haunted doll-like roles. She seems to live them in a way that makes one worry a bit about her life beyond the stage. In any case, the two dancers painted a vivid portrait of co-dependency. If the first woman dominates the man through sex, the struggle here is more complex, and darker. The second ballerina is both manipulated and manipulator; she exerts control through the dramatization of her own weakness. She allows her partner to handle her like a rag doll, roll her in his arms, push her knees together uncomfortably. Meanwhile, she carefully measures the effect of her effete femininity, affecting pretty, fetchingly limp, folded poses. When her partner strays, she calls him back. It’s a rather twisted pas, and Taylor and Fairchild brought out all the kinks. The fact that Fairchild is younger doesn’t hurt either.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

In comparison, Monumentum Pro Gesualdo was rather pallid. Teresa Reichlen was creamy and luxuriant, as always, but rather too detached for this melancholy little neo-Renaissance ballet, with its courtly formations and anxiety-producing Gesualdian harmonies. Jonathan Stafford, débuting in the male lead, remained a cipher. Both looked rather more at ease in Movements for Piano and Orchestra, the short ballet with which Monumentum is normally paired. No one does angular, Modernist chic like City Ballet.

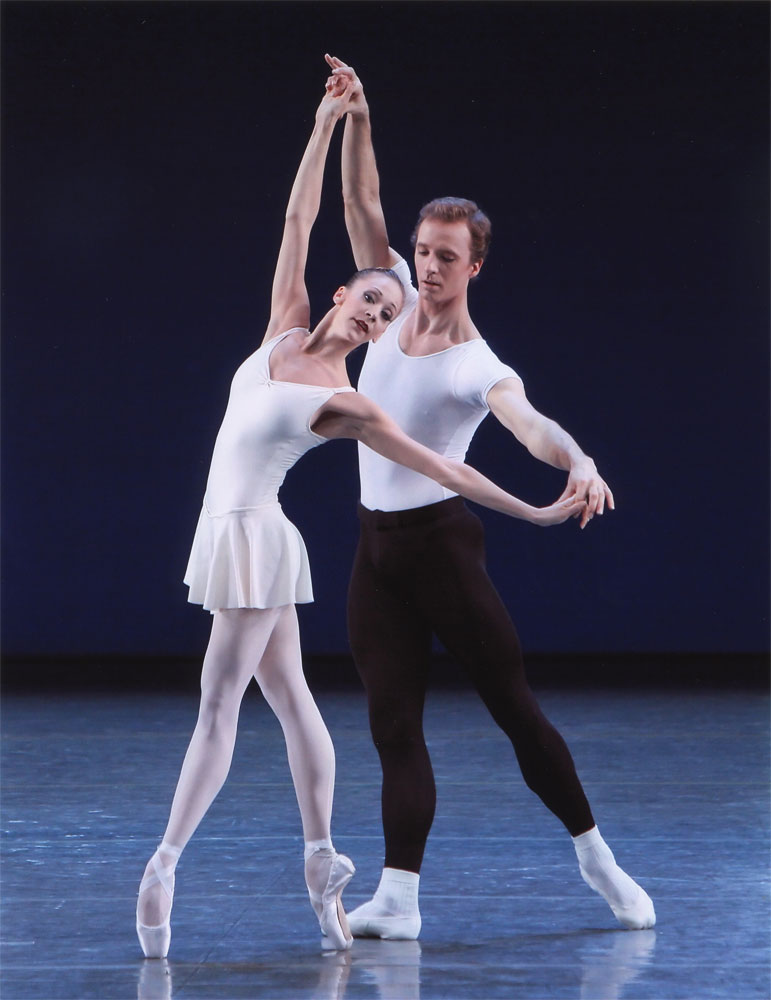

Chase Finlay had his début in Duo Concertant, a ballet that always turns out to be better than one remembers it to be. The beginning is irritatingly coy: the two dancers stand at the piano and listen to the first movement Stravinsky’s duet for piano and violin in a kind of dreamy reverie. There’s something deeply unconvincing about this moment: it’s not the kind of music one would daydream to, and one can’t help but think that the two are just gearing up for the actual dancing. But despite the artifice, the playfulness of the choreography and its sentimental love story wins one over. Finlay was exceptional. He still looks extraordinarily young, but one sees the man beginning to surface in the boy. He has an innate sense of phrasing, an easy warmth in his partnering, and a deep, plush plié that gives him a feline air. At one point the choreography calls for a leap that lands on one knee, at his partner’s feet. I had never really noticed it before, but in Finlay’s hands it became the hyper-dramatic gesture of a young man: love me! Megan Fairchild, too, wins one over with her pliant, uncomplicated femininity. She doesn’t overdo it.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

The evening closed with the explosion of energy that is Symphony in Three Movements, a forceful performance by the whole company that closed the uneven program on a high note. But with more nuance, and a lighter touch in the orchestra pit, the quieter ballets could be – and should be – just as exciting.

You must be logged in to post a comment.