© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Lynette Halewood with her personal selection of London dance memories this last year…

The London Olympics affected our dance experiences this year in various ways. One was that there were none of the usual major Russian visiting companies appearing in the late summer. But it also meant an extended season for the Royal Ballet into July, and a lengthy visit from the Pina Bausch company in the run up to the Games. Also it spawned a plethora of Olympics-themed ballets, some rather more successful than others. Here follows some reflections on viewing dance in London in 2012, and what was memorable about it, and what perhaps ought to have been.

January

This was a month where ambitious projects tried hard but didn’t quite deliver. (This in many ways turned out to be the theme of the year). Survivor, the event at the Barbican devised by musician / choreographer Hofesh Shechter and the sculptor / designer Anthony Gormley was not really a dance performance, more a music event with occasional dance moves and filmed projections thrown in. Nevertheless, it makes my list of memorable items this year for its tremendous use of the Barbican space, the fullest and most enterprising use of this venue I’ve ever seen. The stage was stripped right back, giving the audience a vast vista through to the huge storage spaces behind it. Bodies of dancers descended from the flies. The performers filmed themselves vanishing down ventilation shafts then popping up through the stage floor in front of us. That distinctive Barbican safety curtain (like the jaw of an enormous steel animal) closed and then reopened to bring us 100 drummers on stage all hammering away for dear life. It needed more dancing to make the impact, to give it focus, but still the ambition and scale of it was impressive.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Ivan Putrov’s Men in Motion programme at Sadler’s was an interesting idea to show the development of the male dancer over time, but it wasn’t very successful in execution (organising international visitors and their visas is a tricky business and the programme was cut short). Putrov and Sergei Polunin (immediately after his sudden shock exit from the Royal Ballet) got all the headlines but the best dance performance in a thin programme was still undoubtedly by Daniel Proietto in the Russell Maliphant Afterlight solo.

February

This month Russell Maliphant presented a single performance of his new work, The Rodin Project, at Sadler’s. This returned there for more performances in October. By then, some of the dance had become smoother in motion and less staccato in delivery. It may still be a work in progress but even in its earlier outing it was clear that this was a new departure for Maliphant, incorporating more street dance moves into his already eclectic vocabulary. Rodin’s work is referenced in some poses but the dancers become more like the sculptural material itself being moulded and poured. Michael Hulls’ lighting in the first half paints the set with ravishing washes of colour. The second half features a quizzical duet for two men and a wall which is like nothing else in any dance performance this year. It wasn’t completely successful but it was still more interesting in what it was attempting to do than less ambitious works.

© Laurent Phillipe. (Click image for larger version)

March

This is always a bumper month – why can’t the Powers That Be be kinder to our diaries in March and October?

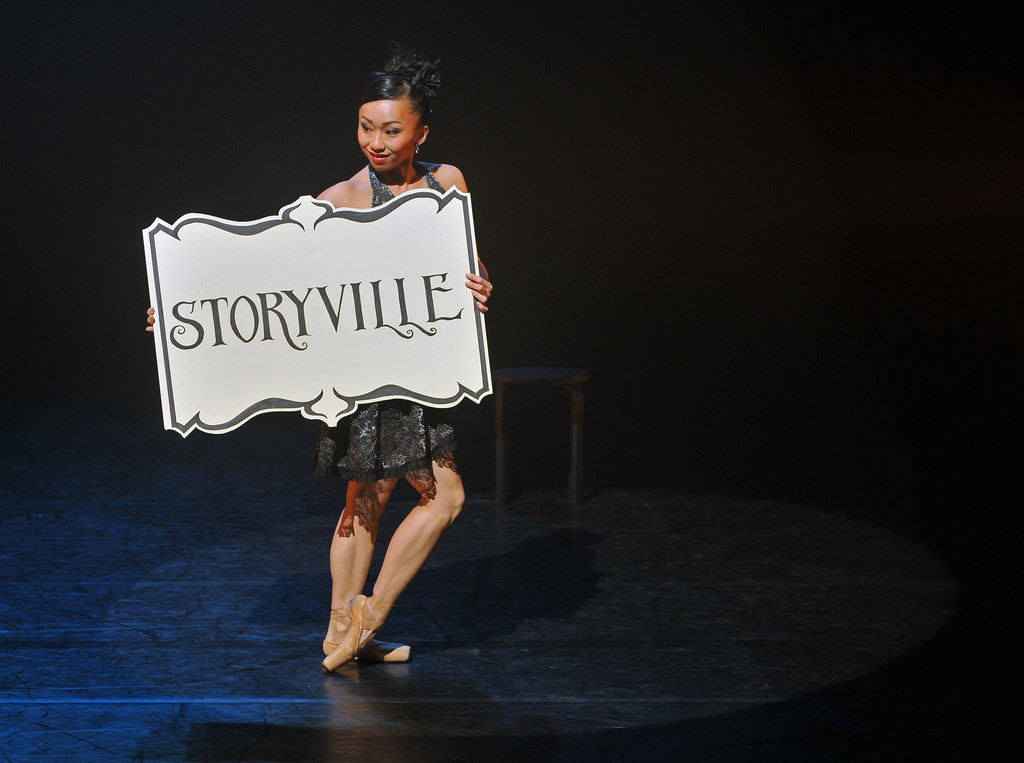

Ballet Black are regulars at the Linbury in March and their enterprising collection of new ballet commissions is always welcome. Many of their pieces are plotless but this year Christopher Hampson’s Storyville gave them a narrative and characters to get hold of, and they inhabited it with gusto. This was a very clear piece of storytelling with lots of audience appeal, achieved by the innovative company on a miniscule budget.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Birmingham Royal Ballet brought their lovely production of Ashton’s The Two Pigeons to the Coliseum. This was a bittersweet pleasure: a delightful and sensitive performance of this charming work, but this was the last time I was to see Robert Parker on stage. He retired to direct Elmshurst School of Ballet. He will be much missed. Nao Sakuma hit just the right note as his irritating but still lovable girlfriend.

© Bill Cooper. (Click image for larger version)

BRB also brought us Sir Peter Wright’s amiable production of Coppelia. It’s been tinkered with over the years. I confess I preferred his previous ending of Coppelia when the doll actually does come to life at the very end and Old Dr Coppelius can go away happy, but this has gone.

Christopher Wheeldon had made some revisions this season to his Alice in Wonderland at the Royal, splitting up the overlong first act into two more manageable chunks. There was a remarkable performance as Alice from Beatrix Stix-Brunell, the debut of the year. It was hard to believe the role hadn’t been made on her.

© Hugo Glendinning. (Click image for larger version)

In a curious symmetry in the same month Javier de Frutos had also revised his The Most Incredible Thing at Sadler’s Wells. This full-length work, with a score by the Pet Shop Boys, had premiered the previous year, more or less at the same time as Alice. De Frutos also changed the position of the interval, among other revisions. Neither of these works has quite solved its structural problems. Both sold out completely the year before: but where Alice is still packing them in, it seems that The Most Incredible Thing was not doing as well at the box office this time.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

English National Ballet also did not have a completely happy time at the box office with their mixed bills at the Coliseum. They risked a new commission of The Firebird from the very young choreographer, George Williamson. This wasn’t completely coherent but some of it sits obstinately in the memory nevertheless, and was a great opportunity for Ksenia Ovsyanick who put in a really gutsy performance as the Firebird.

April

Liam Scarlett’s new work for the Royal Ballet was much anticipated. Sweet Violets was an overheated and overpopulated narrative inspired by the paintings of Walter Sickert, the 19th century music hall and Jack the Ripper. He attempted to pack far too many characters and plot into too short a space but still came up with some compelling moments that make you want to see whatever it is that he does next. The designs, by John MacFarlane (especially for the theatre interior), were tremendously well done, the most striking pieces of design this year.

© Bill Cooper, courtesy of ROH.

On the same bill was Wayne McGregor’s Carbon Life which appeared to take on territory (loud rock music, the thrust forward pelvis) that normally belongs to Michael Clark. The results were messy. The work was more memorable for the fuss that surrounded it than the actual performance.

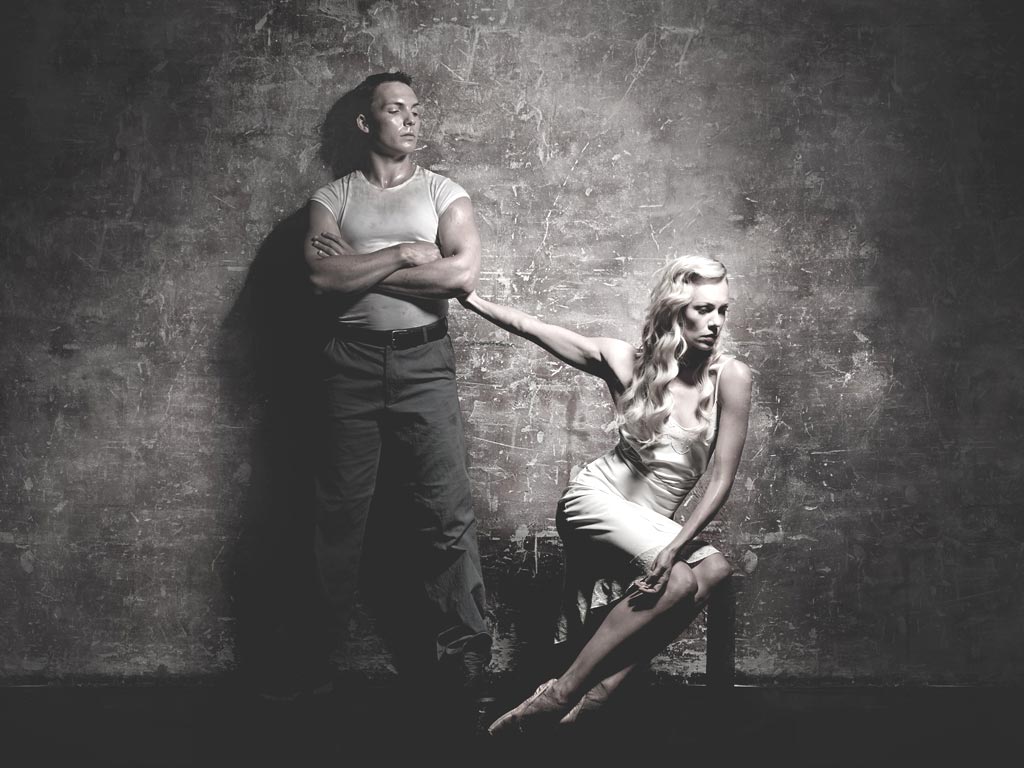

Scottish Ballet’s new production of A Streetcar Named Desire at Sadler’s this month was much praised. It was indeed very cleverly staged and lit, the narrative clearly presented. The energetic cast moved lots of boxes for the set onto which projections sometimes were used very inventively . And yet… why am I remembering the staging much more than the choreography? The actual dance moments themselves seem to have faded from the memory.

© Graham Wylie. (Click image for larger version)

May

This ubiquitous Matthew Bourne popped up again with a revival of some of his earliest pieces including Spitfire and Town and Country. These are sweetly silly and fun but full of sharp observation. Town and Country included some of the daftest moments of the year (I loved those glove puppets…). Bourne is somehow at his most profound and touching when dealing with the trivial. At the profoundest moments of drama or music (as we saw in his version of the Sleeping Beauty at the end of the year) he can appear lightweight.

© Justin Nicholas. (Click image for larger version)

Danza Contemporánea de Cuba returned to London, bringing back a revival of George Céspedes’ Mambo 3XXI which was so popular here in its previous visit. It certainly showed off the energy and casual brilliance of these wonderful dancers. The other items on the bill, commissioned from European choreographers, didn’t work so well. As so often this year, it was a performance where you come away thinking how terrific the dancers are but what a pity the choreography doesn’t measure up.

June

MacMillan’s Prince of the Pagodas was revived by the Royal Ballet after a gap of many years, and though much anticipated, was something of a disappointment. The music was well done: It was fascinating to hear the orchestra imitating the gamelan again. But the work refused to gel on stage. Perhaps different casting might have helped. None of the Fools were as dominant as I recall Kumakawa had been in the role in the1990s, really driving along proceedings. Ultimately not enough seemed to be at stake and we didn’t care enough about the protagonists, which is an odd result in a MacMillan work.

© Dave Morgan, by kind permission of the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

This month was also the beginning of the Pina Bausch marathon, a series of ten productions staged by her company at the Barbican and Sadler’s. Each of the “World Cities” productions was supposed to celebrate a particular city and Bausch’s response to it. What did we know of these places, and of Bausch, by the end ? It would be an interesting challenge to see all these pieces without knowing the titles and see if the viewer could in fact distinguish Istanbul, say, from California. There are far more similarities than differences. Wherever she went she was still in Bauschland, where there are always chairs, pretty print dresses for the women, suits for the men, and always water to be thrown around. Seen in quantity, some reliance on stock situations became too apparent. But the advantage of seeing multiple performances is to get to know the quirkiness of the dancers and their individual personas more fully, and they are a deeply engaging bunch.

© Bo Lahola. (Click image for larger version)

July

It has been quite a year for Matthew Bourne. The run of Play Without Words at Sadler’s confirmed it as his most completely realised and satisfying work so far – subtle, inventive, using the triple versions of the characters to present us with a multifaceted take on their emotions and motivations. The seduction scene on the kitchen table was the sexiest dance moment of the year.

© Sheila Burnett. (Click image for larger version)

The Royal’s triple bill, Metamorphosis – Titian 2012, which ended their season in July was rather too much to take in, and a mix of perhaps too many creative spirits. It was Monica Mason’s farewell as Artistic Director. Again, one must applaud the ambition of the idea, even if not all of it wholly succeeded.

This concept was that current Royal Ballet choreographers would produce three new ballets in collaboration with contemporary artists and musicians, inspired by three specific works by Titian in the National Gallery, all featuring the goddess Diana. More than one choreographer was involved in each piece. Sometimes the joins were rather obvious, and the danger of design by committee was obvious. It might have been more interesting to reverse the order in which the three works were presented. If we had begun with the Scarlet / Tuckett / Watkins more traditional narrative work showing Actaeon’s death torn apart by his hounds, and then moved on to the merest hints of narrative in Trespass (by Wheeldon / Marriott) and concluded with more abstract ruminations of the McGregor/ Brandstrup Machina ,then we might have reacted differently to the veiled emotion of Machina which seemed more puzzling when it opened the programme.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

However, someone should definitely employ Chris Ofili to design for ballet in future. He created a gloriously colourful forest of huge rampant tropical blooms, where the scale of the opera house stage really worked well. But costume design was not his strong point.

Danny Boyle’s Olympic opening ceremony was outrageously ambitious and stunningly successful (rather as the Games themselves turned out to be). It was full of slap-your-forehead-I-don’t-believe-I’m-seeing-this moments. Dance was very cleverly integrated into the performance. The part featuring Akram Khan and his dancers was beautifully lit and staged, and the TV presentation managed to combine the large scale and the intimate very effectively here.

August

Despite the distractions of the Olympics, English National Ballet went ahead with a run of Swan Lake at the Coliseum and were rewarded with good houses. Zdenek Konvalina (who joined the company last year) was new to me in the role of Siegfried and gave a truly elegant and refined account of the role. It’s been a good year for the male dancer (apart from Sergei Polunin, of course).

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

September

San Francisco Ballet had a very successful short season at Sadler’s. Why do we like them so much? They bring us a generous selection of work, much of it new to us, though some from choreographers we know. You could see more new work in a week than in an entire season of some UK companies. The prices are very reasonable. Maybe you won’t like everything on the programme but you do have confidence that Helgi Tomasson, their AD, will have something good on the menu. The dancers are their best ambassadors. There are things you can quibble with, for example some questionable costuming, a few ragged moments here or there, but the open-hearted commitment of the dancers is terrific to see. They don’t have the resources or the traditions of some other big American companies but they really do try harder.

© Dave Morgan and courtesy of San Francisco Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

October

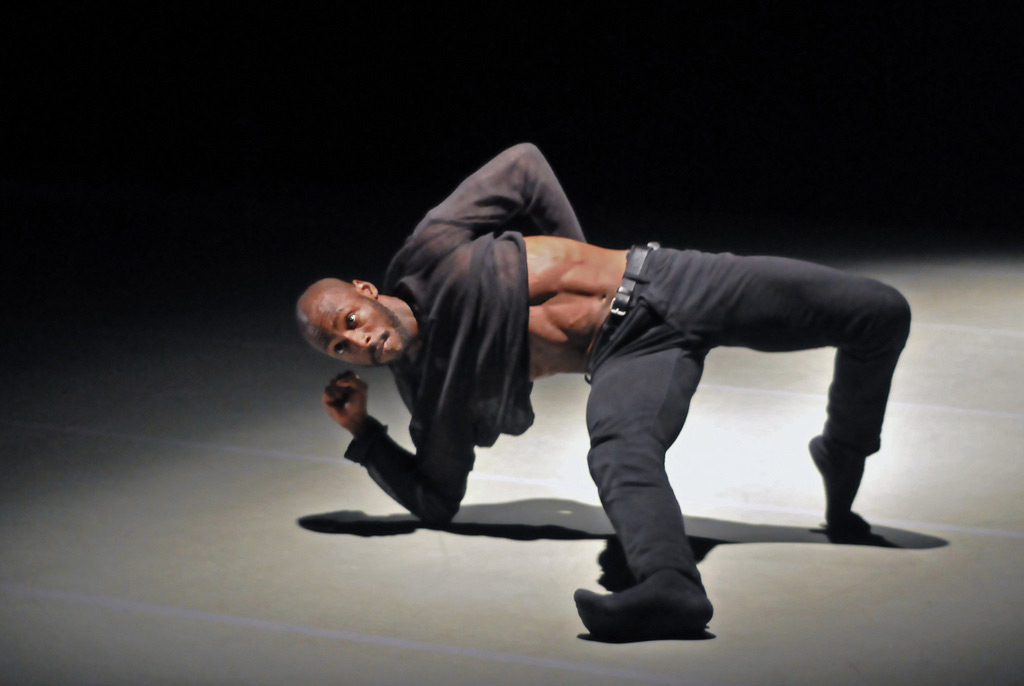

This was a very good month for the male dancer. First off, Martin Lawrence presented Madcap as part of the Richard Alston Dance Company’s programme at The Place. This work is his most successful to date, a continuing flow of invention. The men of the Alston company are all intensely watchable. Nathan Goodman was outstanding as the magnetic centre around which Mapcap flowed. Alston’s short early work, Dutiful Ducks, also got an outing in Rambert’s mixed bill this month and proved a terrific opportunity for the elegant Dane Hurst.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

November

After the safe opening to the season with the box-office-friendly Swan Lake, the Royal Ballet’s Triple Bill this month was a real statement of intent from Kevin O’Hare, the new Artistic Director. It included works from the three who are now all in-house choreographers. McGregor’s work was first made for the ROH, but not all the work was made in house. Liam Scarlett made Viscera for Miami City Ballet and Christopher Wheeldon made Fools Paradise for his own company before it folded. But as a commitment to new work it was cheering. Now he needs to put some female choreographers on the stage.

© Jean-Yves Genoud. (Click image for larger version)

Sideways Rain was an unexpected delight from Alias at Sadler’s Wells. This was a short work based around a simple premise, a stream of dancers pouring endlessly from left to right, crawling, loping, running. This relentless flow of humanity could be us in different stages of evolution, learning to walk, moving towards the light, or maybe toward an inevitable demise. The power of repetition became hypnotic. When one woman turned and moved against the tide it seemed a truly heroic gesture.

December

English National Ballet rely heavily on the box office takings from multiple performances of The Nutcracker .

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

There are opportunities in this heavy schedule for rising stars to shine. I have happy memories of a lovely performance in the lead role by the young Shiori Kase. She provided a charm and calm authority in tune with the glorious music that overcame some of the shortcomings of the production itself.

You must be logged in to post a comment.