© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

American Ballet Theatre

Opening Night Gala: Rondo Capriccioso, With a Chance of Rain, Thirteen Diversions

New York, David H. Koch Theater

22 October 2014

www.abt.org

Scènes de Ballet

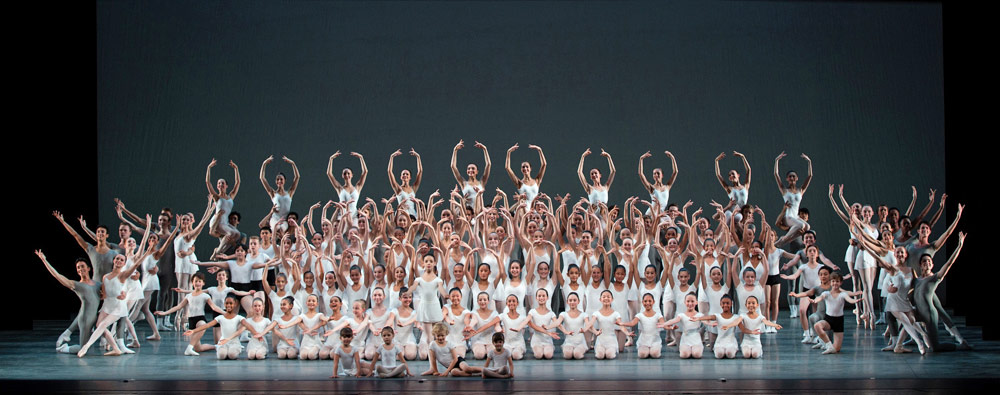

In one of the short films that accompanied Wendy Whelan’s farewell performance at New York City Ballet, the dancer appeared in a sunny ballet studio, teaching the subtleties of the Sugarplum variation to a group of young girls. She spoke of “passing on a philosophy of ballet” to her pupils. Her words echoed in my mind as I watched the ballet – or pièce d’occasion – that opened American Ballet Theatre’s 75th anniversary season at the David Koch Theatre on Oct. 22. Rondo Capriccioso, choreographed by Alexei Ratmansky and set to music by Saint-Saëns, was a simple showcase for the company’s school, something like the Paris Opera’s Grand Défilé, but for munchkins. There was nothing showy about it; and yet, in all its simplicity, it managed to affirm certain core values built into the art of ballet: manners, clarity, musicality, and above all, joy.

More than one hundred kids from the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School – which turns ten this year – took part, augmented by the studio company and ABT apprentices. At times, the stage looked like a mosaic of different-sized bodies come to life. A little girl of six or seven was the protagonist. Like a tiny girl out of a Sempé drawing, she peered into a “mirror” and saw herself – played by another little girl – jumping, spinning, bowing. Then, suddenly, the girl in the mirror seemed to float up into the air, aided by an “invisible” partner. Entranced, our guide stepped through the mirror into a brilliant world full of dancers.

To Saint Saëns’ swooping and excitable music, the mosaic of bodies dissolved – to kaleidoscopic effect. Smaller groups began to sweep across the stage, demonstrating the abc’s of ballet, from simple movements of the legs to jumps to fouetté turns and avian lifts. The charm was in the details: in a diagonal of dancers increasing in size, and also in speed, streaming across from left to right, in the juxtaposition of two boys doing à la seconde turns–with one leg out to the side – on one beat, while five boys did flickering brisé jumps behind them, their bodies rocking to another beat. Nothing was rigid or stiff. The physical freedom that comes from mastery of technique was the theme.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

If only the promise offered by Rondo Capriccioso had been borne out by the ballet that followed. Liam Scarlett’s With a Chance of Rain is the young Briton’s third ballet to première in New York in as many seasons. A pattern is beginning to emerge. There is his penchant for murky lighting and his taste for hyper-dramatic music, and most of all, his oppressive take on the relationships between men and women – with the men doing most of the oppressing. In Acheron, made for City Ballet last February, this brooding interaction between the sexes looked like a thematic choice. But now it seems more like a state of mind. It seemed Marcelo Gomes and Hee Seo might never detach from each other in the final pas de deux. To these now-recognizable characteristics, Scarlett added a strange, jokey coarseness that seemed completely out of tune with the work as a whole.

The piece begins much as Acheron had, with a group of dancers spread out across the stage, their backs to the audience, floating in a kind of netherworld. The notes of a Rachmaninoff piano prelude (played by Emily Wong) billow and curl around them. Slowly, portentously, individuals emerge from the group, looking over a shoulder, moving their upper bodies and arms in calligraphic shapes. (Much of the impulse in Scarlett’s work seems to come from the upper body, which gives it a sensual, three-dimensional quality.) Later, women appear out of the inky darkness, stepping forward with ominous determination, just as Tiler Peck did in Scarlett’s recent Funerailles, for City Ballet. They look like they’re coming for your soul.

A pas de deux set to a march (Op. 23 no. 5) paired Misty Copeland – dancing with a new authority and lushness in the upper body – with James Whiteside. But what began as a sexy tango devolved into a feast of breast and butt squeezing. The effect was odd – was it meant to be funny? – and rather off-putting. Later, two couples shared a section of lyrical, almost ballroom-style partnering, impeccably danced by Gemma Bond, Devon Teuscher, Joseph Gorak, and Sterling Baca. But no! The men unceremoniously dropped the women on the floor. Finally came the endless pas de deux for Gomes and Seo, full of clingy caresses and sudden, abrupt manipulations. Scarlett’s choreography is musical and stylish, but, at least in this ballet, there are niggling issues of tone and a kind of suffocating passivity to the footwork.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

Christopher Wheeldon’s Thirteen Diversions (2011), the final piece on the program, came as a relief. Seeing it again after the New York premiere of Wheeldon’s Alice revealed a certain affinity between the two works, particularly in the elegant, Ashton-like suppleness of the upper body and detailed pointe-work. Wheeldon pays great attention to the twist of the wrists, the sensitivity of the arms. In Alice, the protagonist is forever pointing at something; and here, too, there is a duet in which two women point their fingers, at each other and around them like clocks.

It’s a very pleasing ballet, beautifully-structured, well suited to the music (Britten’s “Diversions for Piano”), and handsome to look at. (The black and white costumes by Bob Crowley are also quite flattering.) Wheeldon creates a series of striking figures that build from low to high, crowned by a dancer held aloft like an angel in a Baroque painting.

The ballet contains two central pas de deux, one more classical – danced with great polish by Gillian Murphy and Thomas Forster – the other more dramatic. Though the latter has its moments of heavy-handedness – the man seems to be forever grabbing the woman’s ankles or wrestling her into overhead, upside-down splits – it was danced with such refinement by Isabella Boylston and Cory Stearns that one barely noticed.

In any case, one was grateful for some real dancing. Because, as Ratmansky’s little piece reminds us, ballet is also about movement and light.

Who played the violin solo in the Saint-Saens? That’s a wild piece to play! He/she should be mentioned in this review.

Dear Sarah, it was Benjamin Bowman, the company’s new concertmaster. As you’ll see, I’ve written about him at length in my next review: https://dancetabs.com/2014/10/american-ballet-theatre-raymonda-divertissements-jardin-aux-lilas-fancy-free-new-york/