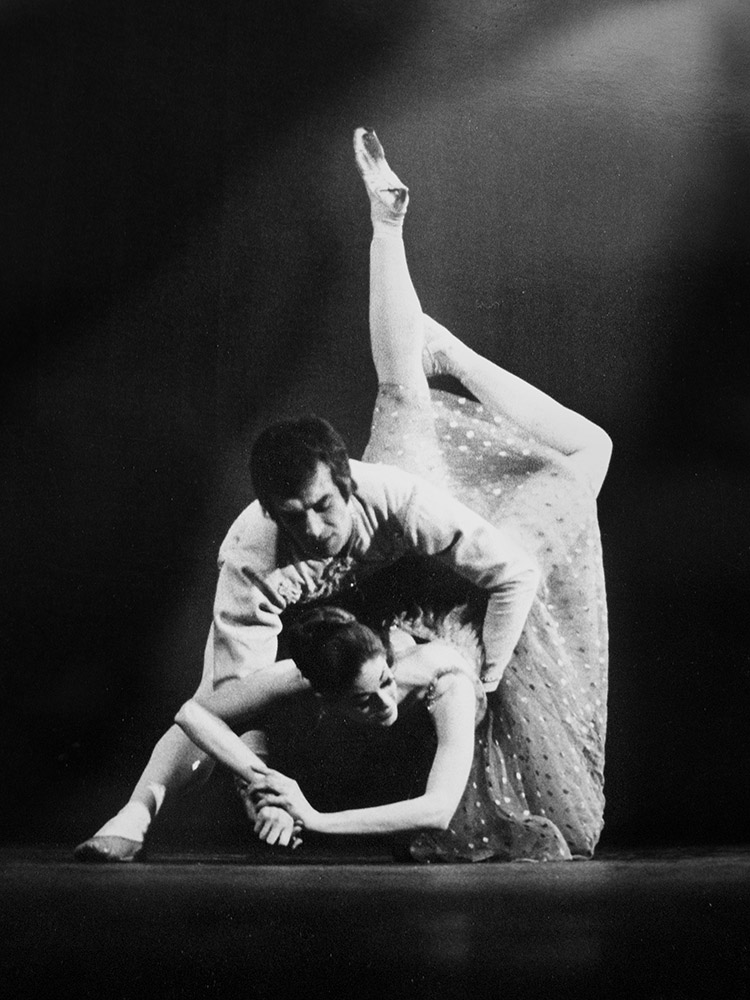

© 2011 Mark Kehoe, courtesy Sunday Express. (Click image for larger version)

Jeffery Taylor: 1 May 1938 – 25 September 2019.

Jeffery Taylor – the real Billy Elliot

Jeffery Taylor, who died in the autumn, aged 81, was a professional dancer for sixteen years before going on to become a dance critic, following a successful interlude as a manager in the printing industry. He believed passionately that one needed to have been a dancer in order to pass judgement on other dancers and for many years Taylor proudly asserted that he was the only ex-dancer working as a dance critic. During his brief tenure as President of the Critics’ Circle, he attempted unsuccessfully to broker a scheme for mentoring artists towards the end of their performing careers to become critics. It was not taken up because age-enforced retirement is rarely an issue in other branches of the arts (drama, film, literature, music, visual arts).

Taylor had an unhappy family life as a child, growing up with his mother and elder sister in Urmston, which he described as “a working class cultural desert on the outskirts of Manchester”. He lived in the harsh reality of a fatherless family at a time of food rationing, massive devaluation and spiralling costs of living. One day he came home from school to find that the bailiffs had removed almost all the furniture. Suffering from malnutrition, he was so worried about his weak and misshapen legs that Taylor feared having to wear corrective iron callipers. In later life, he wrote that he suffered many beatings as a child.

It was seeing a ballet performance, aged eleven, that made him grasp the potential of the art to make his legs stronger and – with the support of his doctor but against his mother’s wishes – Taylor took his first step towards a lifelong affair with ballet by turning up at Irene Williamson’s class with a hard-fought 2/6d in his hand. On the eve of the release of Stephen Daldry’s film, in 2004, Taylor wrote a feature declaring that he was The Real Billy Elliot and similarities between his life and the fiction were many: a one-parent Northern working-class family in an endless struggle with poverty.

Billy Elliot ends with the father accepting his son’s passion for ballet, a rapprochement that Taylor never achieved, writing that the relationship with his mother was “a bitter battle until the day she died.” He may have had the half-a-crown needed for that first lesson, but for almost all of the five years he studied with Mrs Williamson (ironically, Billy’s fictitious teacher was Mrs Wilkinson), he did so for free. After moving to London, aged 16, Taylor lost touch with his mother, meeting her just once more, shortly before her death. “We had a mutual respect, if grudging, for never giving up on what we believed,” he wrote in 2004.

From Mark Kehoe, courtesy Sunday Express. (Click image for larger version)

Taylor gained a place at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School (now The Royal Ballet School), then in Baron’s Court, West London, although at his first audition he was told by an alarmed invigilator that his weakened legs were so bad that he should never dance another step if he was to avoid spending the rest of his life in a wheelchair. Thankfully, another teacher, Claud Newman intervened and seeing a promising prospect, developed a twelve-month programme of exercises to strengthen Taylor’s knees. For the whole of his career as a dance critic, Taylor was often drawn to comment on the strength of male dancers’ legs.

After his graduation, Taylor briefly joined the Covent Garden Company until he was called-up for national service. That demand to serve his country was cancelled due to a change in policy, by which time Taylor had already spent a year out of the dance studio. He couldn’t afford to take professional class and was desperate for help. By chance, he met Joanna Denise, a teacher who specialised in rebuilding dancers after injury. During his first class with her, two professional dancers entered the studio late and in mid-conversation. Denise stopped the class and told them to go back outside. Taylor later recalled her rebuke: “Coming into a studio for class is like coming into a church. You should have that much respect, and if you haven’t, don’t bother coming back.” He was impressed by this strength of attitude and love of dance. From then on Denise allowed him to take classes, paying only what he could afford. “Not only did she rebuild my technique, she literally changed my life,” Taylor wrote in 2016. “She made me see not only ballet, but art, in a different way; I had found a substitute for religion.” Taylor and Denise married in 1969, remaining inseparable until her death, in 2010. They had no children.

The correct teaching of ballet was akin to a religious observance for Taylor. His perception about the decline in Britain’s classical dance led to a campaign to reverse what he described as “…a huge erosion of standards with political correctness.” In October 2006, Taylor gave a controversial lecture arguing that child protection policies imposed a virtual ban on ballet teachers touching students. Taylor maintained that touching is essential to achieve the unnatural physical regime that constitutes classical ballet technique. “Ballet positions confound our natural habits and instincts,” he explained at the time of the lecture, arguing that children have to be coaxed into unnatural positions by physical manipulation. “There is no way a child can understand how you straighten your lumbar region, how you tuck your hips underneath you.” His argument that touching in the act of teaching dance was essential and should never be associated with physical abuse was passionately put and led to appearances on TV and radio.

Armed with his rebuilt technique, Taylor became a founder member of Western Theatre Ballet, established by Peter Darrell and based in Bristol, it was Britain’s first regional ballet company (in 1969 it was to move base to Scotland, eventually becoming Scottish Ballet). After leaving Western Theatre Ballet, Taylor continued to guest with ballet companies in Europe before migrating to musical theatre, appearing in the West End in Hello Dolly and The Great Waltz and as a regular dancer on ITV’s Sunday Night at the London Palladium, where he performed in support of such stars as Judy Garland, Jane Russell, Danny Kaye and Eartha Kitt. “Television changed my life,” Taylor said in a 2014 interview. Gradually, he transitioned from dancing to acting, appearing on stage in Chez Nous with Albert Finney and The Card with Jim Dale. He also had a small role in the 1970 movie, Song of Norway.

© 2011 Mark Kehoe, courtesy Sunday Express. (Click image for larger version)

Taylor left the theatre in 1986 and became The Mail on Sunday’s first ballet critic and then Arts Correspondent, having some responsibility for launching that newspaper’s Review Section. His work as a critic and dance writer took in several other titles, including The London Evening Standard, Daily Telegraph, Sunday Mirror, Daily Mail and OK! Magazine. As well as dance, Taylor also reviewed classical music, books and he was briefly a travel writer. Since 2001, he was dance critic, columnist and feature writer at The Sunday Express, work that he continued until the later stages of his illness.

In 1994, Taylor wrote the authorised biography of Irek Mukhamedov, the renowned star dancer of the Bolshoi and the Royal Ballet. With Mike Dixon, he co-founded the National Dance Awards in 2000 and he became President of the Critics’ Circle in 2013, although he resigned from the role mid-term, having been diagnosed with dementia. A private person to the end, Taylor chose not to reveal this to friends and colleagues, continuing to work for as long as possible. In his last days in hospital, colleagues brought programmes from the previous night’s performance and, unable to speak, he would point to the dancers he admired: his love affair with dance continuing until the very end.

You must be logged in to post a comment.