© Christopher Duggan. (Click image for larger version)

Fall for Dance

Program II: Who Cares? (excerpts), To Be Seen, Duet from Concerto Six Twenty-Two, Lady Swings the Blues

★★★✰✰

New York, City Center

26 October 2020, streamed through 1 Nov 2020

www.nycitycenter.org

Jam Session

This year’s online version of Fall For Dance closed Monday night with another mixed evening, filmed, like the first, in an empty City Center. It’s not easy to get used to these ghostly performances, which seem to occur not only at a remove, but in a different dimension, somewhere far, far away. The lack of applause is unnerving. When a performance ends, the curtain simply descends in silence, and that is that. It’s impossible not to feel nostalgic for the screaming audiences that fill the seats in normal times.

Like the first program, this one contained a mix of old and new, ballet, modern dance and, in this case, tap. The dancers were all well-known figures from the New York scene. (What is happening with the less well-known dancers, one wonders? Are they, too, getting opportunities to work?) And as with program one, some pieces worked better than others in the online format. Surprisingly, perhaps, it was the tap solo, by the wondrous Dormeshia backed by a trio of jazz musicians, that felt the most alive. Or not so surprisingly: it was the only dance to be accompanied by live music. The others felt flattened by the irreality of recorded sound, which eliminates the element of surprise and the exciting back and forth between musicians and dancers in a live performance.

© Christopher Duggan. (Click image for larger version)

Dormeshia’s solo, Lady Swings the Blues, was all about that back and forth, a conversation between the dancer, and in particular her feet, and the other instruments. The performers watched and reacted to each other, smiling with understanding. Her solo started out nice and easy; she was part of the musical ensemble, indistinct from the others. Gradually, she developed her own melody and counter-rhythm – she has the most melodious sound in the biz. After a little while she broke into rhythmic variations, virtuosic, but always with that easygoing feel, never showy, never trying to throw off the group dynamic. After an a cappella cadenza, she returned to the group for some call and response with the drums, followed by a big finale, like the climax of a fireworks display. Then she and her fellow musicians brought it home, nice and easy, with a finessed foot and outstretched arms. It was glorious.

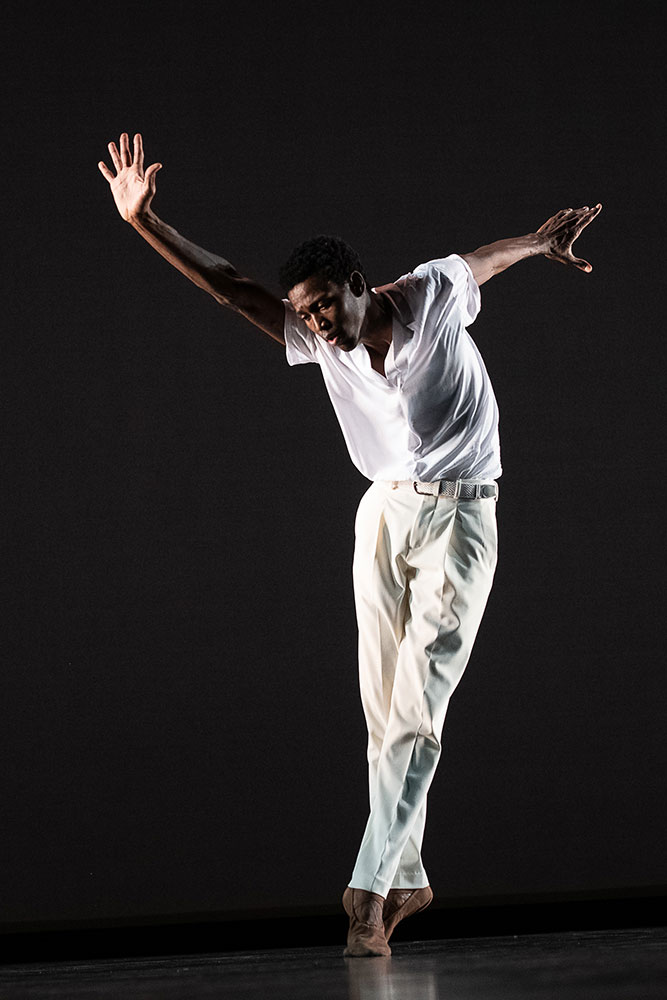

The other highlight of the night was a new solo by Kyle Abraham for the elegant American Ballet Theater dancer Calvin Royal III, who has just been promoted to principal dancer. Royal is a dancer of great intimacy; he brings you in, so that you can almost hear him thinking. Abraham’s To Be Seen attempted to capitalize on this quality, with the little gestures that characterize much of Abraham’s work: a smoothing of the shirt, a hand to the head, a swinging walk that brings the everyday into the more stylized language of dance. Abraham could not resist including a pose from Balanchine’s Apollo, a role recently débuted by Royal: standing with his back to the audience, he held his hands up high, palms flattened, like an Art Deco statue. Later, there was a different kind of lifting of hands, an act of surrender in the face of violence. It hurt the heart, reminding us of the many scenes we’ve seen this year of violence against black people, and black men in particular.

© Christopher Duggan. (Click image for larger version)

All in all, though, the solo didn’t really capture the essence of this dancer, or reveal anything new about him. Part of the problem was the music, the generic and over-used Boléro by Ravel, rendered even more generic by being recorded. (Could we declare an all-out ban on the use of Boléro for a decade or two?) The piece is also too long; Abraham seemed to run out of ideas about halfway through, reverting to balletic clichés: beautiful tendus, charming gargouillades, a manège of grand jetés, around the stage. Royal danced quietly, reflectively, with beautiful lines and introspection, but this we knew already.

© Christopher Duggan. (Click image for larger version)

Excerpts seem to work least well in this context, and so it was with the three women’s solos from Balanchine’s Who Cares? The ballet, set to chirpy Hershy Kay renditions of Gershwin, was simply the wrong choice: too brassy, too artificial for the occasion. Lifting these sections from the larger context of the ballet makes the situation worse. The crisp, complicated combinations of fiendishly difficult pointework are all show with little depth. It feels like a competition between the three dancers, Ashley Bouder, Tiler Peck, and Brittany Pollack, all fantastic but somehow too smiley, too intent to please.

The final piece of the evening was the pas de deux from Lar Lubovitch’s Concerto Six Twenty-Two, set to the adagio from Mozart’s famous clarinet concerto. It was performed by two more New York City Ballet dancers, Adrian Danchig-Waring and Joseph Gordon, partners in life. This delicate work was was created in 1986, in the midst of the Aids epidemic; Lubovitch has called it a portrait of the “grace and dignity of friendship” in time of crisis. Two men, dressed in tennis whites, support and complete each other, with gentleness and care. They embody male beauty and grace, like characters in a Forster novel. It is a touching piece, and these two particular dancers performed it with simplicity and lyricism. But it is not a dance well suited to the screen. The overwhelming sadness that catches your heart in a theater feels very, very distant here.

© Christopher Duggan. (Click image for larger version)

But what can we do? This is what we have now. Fall for Dance has made an admirable effort to produce something of value in extremely difficult circumstances. And it has had some successes. That’s all we can ask for.

You must be logged in to post a comment.