© Matthew Holler/Sarasota Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

Sarasota Ballet

Digital Program 3: Othello and excerpts from Summertide, Clair de Lune, The Mirror Walkers, The American, The Infernal Galop, Concerto

★★★★✰

Streamed from 1-5 January 2021

www.sarasotaballet.org

Deprived of live performances to celebrate its 30th anniversary, Florida’s Sarasota Ballet is making a series of digital programmes available to subscribers, filmed on stage without an audience. So far, each programme has consisted of short works and excerpts from the company’s repertoire, using a limited number of dancers. Program 3 features all-British choreographers: Peter Wright, Peter Darrell, Christopher Wheeldon, Matthew Bourne and Kenneth MacMillan. The exception is a solo by American Dominic Walsh, created for his own contemporary dance company.

Since Iain Webb became Sarasota Ballet’s director in 2007 it has staged many of Frederick Ashton’s ballets, as well as introducing works by UK born or based choreographers. For Program 3, former principal dancer Margaret Barbieri (Webb’s wife and assistant director at Sarasota) has staged excerpts she knew well during her career with Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet. Some of the selections are probably unfamiliar to American audiences, as well as to British ballet fans of a younger vintage.

The opening work, a quartet from Peter Wright’s Summertide (1976), originally featured Barbieri and David Ashmole as the leading pair. Set to the second movement of Mendelssohn’s Piano Concerto no 2, it was made for Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet and revived by Wright for Sarasota Ballet in 2015. The four dancers appear to be nature spirits, drifting serenely in dappled costumes in front of a backcloth in ochre and blue. The designs are by Englishman Dick Bird. Two of the men, Harvey Evans and Thomas Leprohon, seem to be clones, sharing the same moves and poses. They escort a woman, Ellen Overstreet, delivering her to a third man, Ricardo Rhodes, for an intimate pas de deux, before all four dance together and embrace in picturesque clusters.

Because there are echoes of Ashton’s choreography in the way the two ‘side’ men stand behind each other or bookend the central pair, Summertide could be seen as a dewy-eyed homage to Monotones or Symphonic Variations. Wright’s quartet is pleasant but insubstantial.

The second work by Wright, The Mirror Walkers pas de deux, has often served as a gala number (including a Royal Ballet one in 1971 with Merle Park and Desmond Kelly). Its title comes from a ballet Wright created for Stuttgart Ballet in 1963, in which a girl dances alone in a rehearsal studio, watching herself in the mirror. A man appears behind her, dances with her, then vanishes. They exchange places and she enters a world beyond the studio mirror. In the pas de deux, the man and woman, both in white, keep reprising their walk together, followed by variations of dreamy lifts to passages of Tchaikovsky’s Suite for Orchestra no 1. Only after a while does small Ryoko Sadoshima acknowledge the presence of tall Richard House as he raises her higher and higher; perhaps she is seeing him in the imaginary mirror until she runs to him and he carries her off.

The most dramatic work in the programme is Peter Darrell’s one-act Othello, acquired by Sarasota Ballet in 2020. Darrell created it in 1971 for the touring company led by Galina Samsova and André Prokovsky that became New London Ballet. Othello then entered the repertoire of Scottish Ballet, founded and directed by Darrell until his death in 1987. Best known to Scottish Ballet’s audiences, his Othello has now been disseminated digitally to worldwide viewers – albeit for a short period.

© Matthew Holler/Sarasota Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

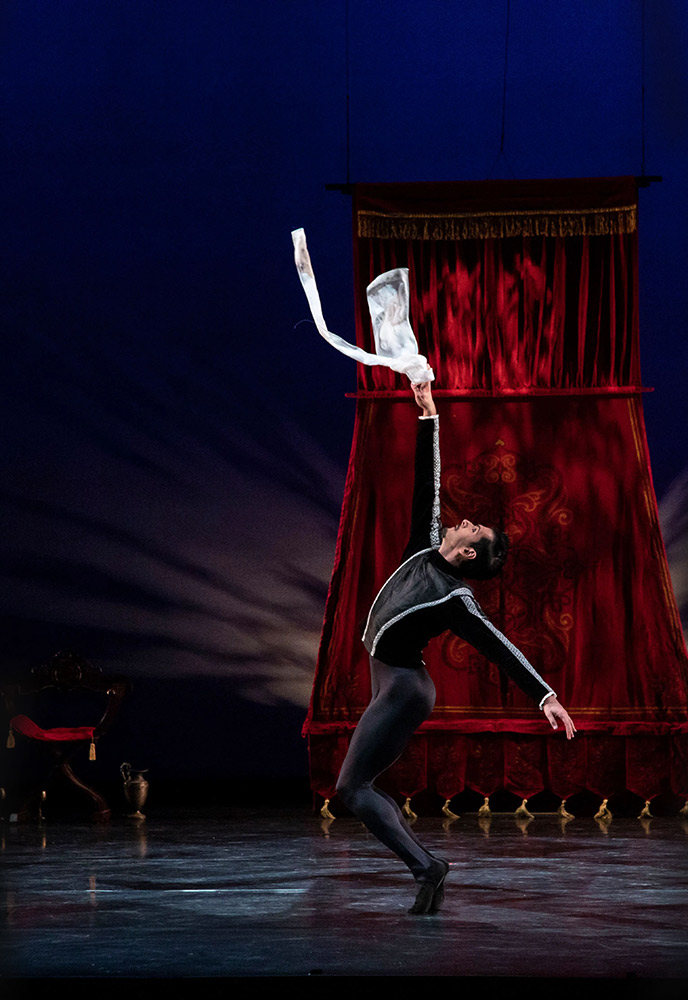

Like José Limon’s The Moor’s Pavane, it compresses Shakespeare’s play into an intricate dance for the principal players, with Iago as the evil manipulator. Ricardo Graziano’s Iago is a master puppeteer, setting up a quartet of unsuspecting victims, including his abused wife, Emilia (Janae Korte). The balletic choreography is formalised, with pairs of characters dancing the same steps in order to appear in sympathy with each other. Envious Iago is servile towards Ricardo Rhodes’s noble Othello and overbearing with handsome Cassio (Daniel Pratt), playing him as a naive drunken fool.

The handkerchief, symbol of love and loyalty, has become a long, diaphanous scarf, as lethal as the one in Bournonville’s La Sylphide. Othello uses it to strangle Danielle Brown’s gracious Desdemona. The music is from Liszt’s Faust Symphony, which Kenneth MacMillan later used in Mayerling – Liszt being ideal for expressing frenzied emotions. Othello, maddened by unfounded jealousy, finally realises how much Iago has hated him. Rhodes and Graziano are fine actor-dancers (Graziano is also the company’s resident choreographer); Brown has more limited opportunities as love-struck Desdemona, while Korte makes the most of wronged Emilia. Othello is a period piece, as is Limon’s The Moor’s Pavane, highly theatrical without the ‘realism’ of more contemporary choreographers.

In the second half of the programme, Christopher Wheeldon’s duet, The American, dates from early in his career as a choreographer. It comes from his 2001 ballet to Dvorak’s American String Quartet. I kept expecting later signature moves that didn’t appear: convoluted lifts, flexed feet, splayed knees, acrobatic arching, the woman being dragged along the floor . . . instead, it’s conventionally lyrical pas de deux, well danced by Katelyn May and Yuri Marques. The ballet for six couples apparently reflected Dvorak’s inspiration from the tranquillity of the Great Plains of North America. (Now that Wheeldon is known for his choreography for the musical An American in Paris, the title of his earlier ballet is easily confused with it.)

Before the programme’s conclusion with Kenneth MacMillan’s Concerto pas deux, young Italian dancer Ivan Spitale is given the chance to show off his comedic talents. He performs the solo by Dominic Walsh to Debussy’s Clair de Lune as a white-face pierrot in a too-small black suit. He’s a vulnerable clown, full of perplexed emotions he can’t identify. Spitale’s flexible body seems to be made of plasticine, his feet in purple socks as expressive as his fluttering hands.

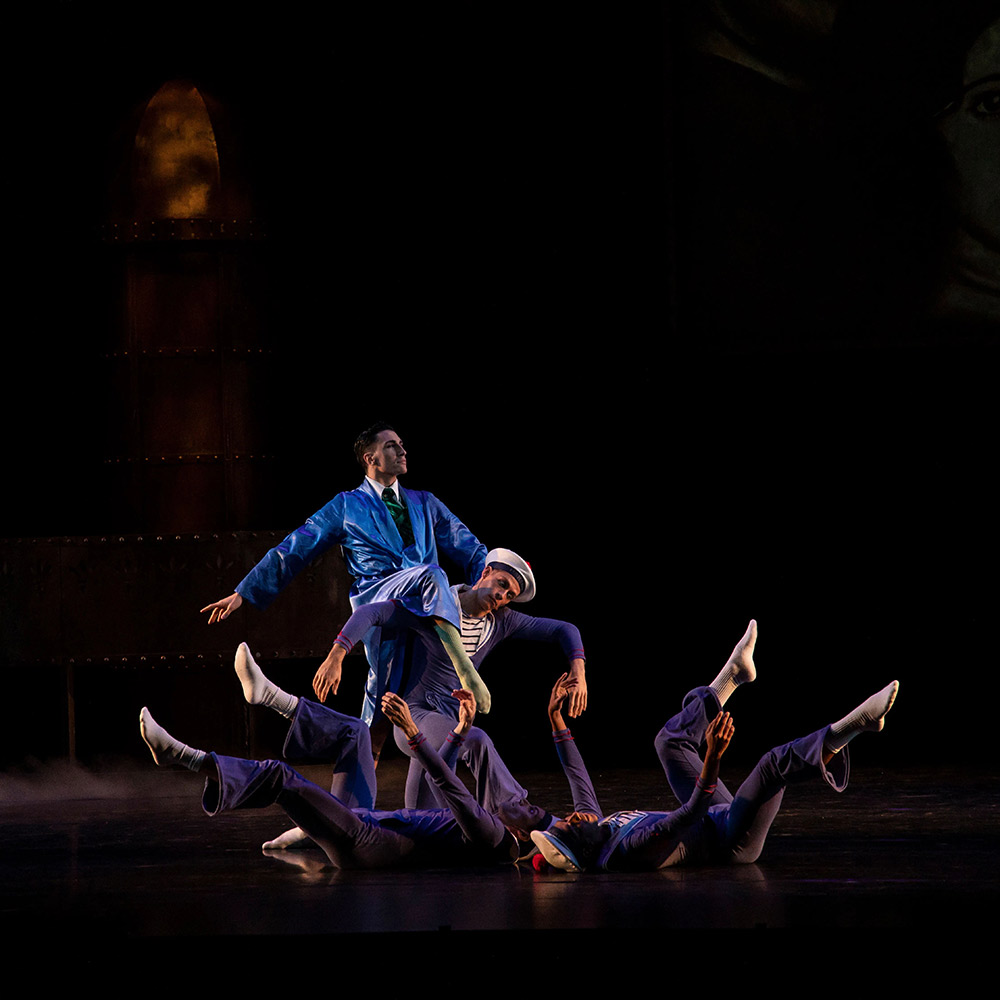

Then, in the Merman’s solo from Matthew Bourne’s The Infernal Galop, he becomes Noel Coward in a silk dressing gown, with flippers for feet. To Charles Trenet’s La Mer, he languishes on stage, joined by three camp French matelots – Daniel Pratt, Lenin Valladares and Ricki Bertoni. Etta Murfitt and Iain Webb, who both know Bourne’s work well, rehearsed the delicious revue-style extract for the company.

© Matthew Holler/Sarasota Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

MacMillan’s Concerto pas de deux , recently seen in the Royal Ballet’s gala streamings, ends Sarasota’s th bill in a reverie to the andante movement of Shostakovich’s Second Piano Concerto. Ellen Overstreet and Richard House are costumed in shades of blue, designed by Deborah MacMillan, instead of orange. Overstreet is mysteriously remote until she meets House’s eyes near the end. He is solicitous in his partnering, watching her carefully, while Royal Ballet men in the role remain impassive, entranced.

The very mixed bill has been sensitively recorded by videographers Meybis Chavarria, Bill Wagy and Andres Paz. The programme is introduced by Webb, a somewhat stilted compere, asking for donations as well as the $35 subscription fee for each programme to keep the company afloat during its 30th year. Further digital programmes are promised before audiences can, eventually, return to Florida’s theatres. In the meanwhile, Sarasota’s dancers on film must perform their customary curtain calls to an empty auditorium, greeted by pre-recorded applause. Although the clapping is canned, it is preferable to the aching silence that greets other virtual offerings during these pandemic times.

You must be logged in to post a comment.