© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

Metamorphosis – Titian 2012: Machina, Trespass, Diana & Actaeon

London, Royal Opera House

14, 17 July 2012

Gallery of 36 pictures by Dave Morgan

Monica Mason on the background to Titan 2012

www.roh.org.uk

Ovid claimed his intention in writing his epic Metamorphoses was ‘to tell of bodies changed to different forms’. In turning Titian’s paintings into ballets, the choreographers have transformed fleshly female bodies into Olympian athletes.

Titian was so skilled at depicting delectably rounded naked nymphs that his paintings were hung in a room reserved for men only in the royal palace in Madrid. In two of the paintings now on display at the National Gallery, Diana and Callisto and Diana and Actaeon, the goddess is a plump, dimpled creature; only in the third, The Death of Actaeon, is she actively Amazonian. In the Royal Ballet’s triple bill, the multiple Dianas are muscular, arched into crescent moon shapes as they triumph over their prey.

The seven choreographers’ brief was not to imitate Titian’s paintings but, in Wayne McGregor’s words, to use them a ‘trampolines for a new set of expressions’. Aptly, the jumping off points for all three ballets were the designs, commissioned by the National Gallery from three well-known artists. As in Diaghilev’s day, the promise of visual excitement has enticed audiences into the otherwise daunting realm of contemporary ballet to modern music. The designs and music will have an after-life, the choreography probably not. Monica Mason’s legacy will be the fact that this bold collaboration has stimulated such widespread interest.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Conrad Shawcross’s metal monster dominates the opening work, Machina, once it whirrs into fury. At first the stage is bare, a blurred light veiled by scrims suggesting the moon. Contrasting pas de deux ensue, the first for Leanne Benjamin with Carlos Acosta. He seems a hunter, burly and questing, she a vulnerable, chaste nymph. When their neo-baroque music by Nico Muhly gives way to shimmering strings, Tamara Rojo appears as a moon goddess, arms curved, while Edward Watson’s limbs are as angular as antlers. Their pas de deux will be reprised at the end, transformed by emotion.

Acosta and Watson dance a combative duet in counterpoint, both men physically distinctive in the way they move. As the scrims lift away, the vast Diana machine is revealed, splay-legged at the back of the stage. The source of the mysterious moonlight is a beam at the end of a blind probing arm. When Acosta is left on his own, the arm-arrow threatens him, flailing angrily and noisily. Its actions have been programmed through motion-capture of human movements – but it doesn’t necessarily obey its commands. The confrontation between man and machine was more compelling at later performances than on the opening night, when Acosta seemed disconcerted, the robot erratic.

The mechanical zooming attracts attention away from further duets involving Benjamin and Rojo as vengeful goddesses in human shape, escorted by a corps of six, who seem largely superfluous. The ravishing final pas de deux starts in silence with Rojo pointing an accusing finger at Watson – a gesture echoing that of Diana in two of the Titian paintings. Lusciously, they dance intimately together, until she regretfully delivers the coup de grace: Rojo leans forward, her head on Watson’s heart as he raises his arms, fingers branched into a stag’s antlers. It’s as if Diana is mourning a love affair that might have been.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Two choreographers, Kim Brandstrup and Wayne McGregor, are credited with the choreography. While the last, tender duet looks like Brandstrup and the praying mantis moves elsewhere like McGregor, attributions would be unreliable. Scenes fragmented by blackouts and pauses make for uneasy viewing, as do inept exits. Why should dancers have to slink awkwardly into the wings when they’re no longer needed? And does anybody ever check sightlines when an important element of a set is placed at the rear of the stage?

Trespass, the second ballet, is the most coherent of the three. Choreographers Christopher Wheeldon and Alastair Marriott collaborated closely in response to Mark-Anthony Turnage’s score and Mark Wallinger’s setting. Wallinger equates Actaeon’s intrusion on Diana’s privacy with man’s violation of the virgin moon by landing on it. A rocky lunar landscape surrounds a mirrored grotto, its curved surface a reference to astronauts’ visors. Turnage’s music sprinkles shimmering stardust on the ballet’s three Dianas, surges into complex rhythms for ensembles and rejoices in the goddesses’ triumph at the end.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

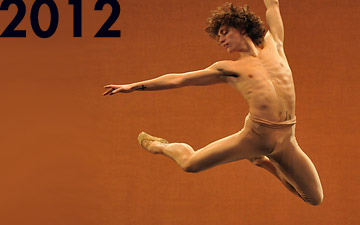

The two Actaeons, Nehemiah Kish and Steven McRae, have a cohort of six men, athletically alert as hunters. Six women form a retinue of nymphs, sometimes shyly modest, at other times huntresses. Beatriz Stix-Brunell, the first Diana, is a young moon, innocent and sensual, ending her pas de deux with Kish curled up on his shoulder, blindfolded. Sarah Lamb perhaps represents the final phase of the moon, suspended in gravity-defying lifts by McRae. Melissa Hamilton takes centre stage as the full moon, Diana in all her glory.

Hamilton is shielded at first by her nymphs, in a fountain shape reminiscent of the underwater scene in Ashton’s Ondine. They dance with her, reflecting and amplifying the crescent shapes she makes within a blue pool of light. Held aloft by the men who have been spying on her, she flexes her feet like flippers, unfurls a leg as lethal as an arrow. There are no yielding Titian contours here; Trespass turns an ancient myth into a modern one, transported to a barren satellite.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

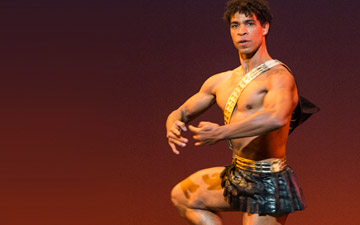

The three choreographers for the last ballet, Diana and Actaeon, were asked by Monica Mason to tell the story of Actaeon’s fate less allusively than the other two pieces. Jonathan Watkins, Liam Scarlett and Will Tuckett split the task between them. Watkins introduced Diana and the hunters who come across her; Scarlett was responsible for the large corps of female attendants; Tuckett handled the pack of hounds who rip Actaeon to shreds when Diana transforms him into a stag for daring to see her naked. All three took turns to show the fatal encounter between Actaeon (Federico Bonnelli) and Diana (Marianela Nuñez) from different perspectives, examining how the mortal and the goddess might have reacted when their eyes first met.

Unless one understands this triple take, it’s baffling to see Bonnelli keep returning for yet another pas de deux with Nuñez when she persists in rejecting him. Costumed in flaming red and gold, she is more Firebird than untouchable goddess. Bonnelli wrestles with her, attempts to tame her, and ends up savaged by his own dogs. He changes into a brown outfit to look like the half-human stag in Titian’s last painting and is pecked to pieces by dancers with dog masks on their hands. Titian’s ravenous hounds are crudely painted but that’s no excuse for such a crassly choreographed killing.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Actaeon’s name is shrieked by the singers of Jonathan Dove’s operatic score, whose arcane text is in Greek and Latin. The instrumentation ranges from blaring brass fanfares and hunting horns to magical gamelan chimings. Its exotic sounds combine with Chris Ofili’s tropical setting to create an atmosphere of rampant sexuality: think Bakst or Douanier Rousseau, a jungle with dogs instead of a tiger. Hotly-coloured mangrove roots lift away in succession to reveal a lustful backdrop (invisible to parts of auditorium) illuminated by a blood-red crescent moon.

Nuñez’s imperious Diana is implacable, very different from Rojo’s remorseful goddess. Her most challenging duet with Bonelli is where she becomes momentarily compliant before resisting him. Othewise she’s all high battements and stabbing pointework, flanked by fierce female bodyguards. There’s no place in this piece for nuanced choreography, enhancing the feminine form with rounded arms or shaded shoulders.

The many competing elements in the triple bill add up to an overloaded evening. Seeing the programme twice confirmed my initial impression that Trespass is the best-wrought work. Lucy Carter’s lighting for it (assisted by Simon Bennison) plays with reflections and deceptions, making Wallinger’s tribute to Titian in the theatre richer than his voyeur’s cabin in the National Gallery exhibition. The other two ballets are interesting as concepts rather than as polished productions. But the programme’s emphasis on creativity and collaboration means that Monica Mason’s farewell contribution to the art form in which she has invested her considerable energy will carry on germinating ideas long after she leaves. A great way to bow out – or in Mason’s way, bound onto the stage to hug her dancers, choreographers and conductors.

You must be logged in to post a comment.