© Boydell & Brewer. (Click image for full version of cover)

Constant Lambert – Beyond The Rio Grande

By Stephen Lloyd

Boydell & Brewer

ISBN 978 1 84383 898 2, hardback, 584 pages

Publishers page

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constant_Lambert

Was the most famous fact about Constant Lambert the reason for his obscurity? Somewhere beneath the royal crest and above the title of each Royal Ballet performance Lambert is still credited as the company’s founder music director. There is a bust in his memory at the Royal Opera House – but biographies about him have been less than complete.

Published in 1986, Andrew Motion’s book had a focus wider than just Constant, covering his father Richard, an Australian war artist in the Middle East during the 1914-18 conflict, and son Kit, manager of The Who. Richard Shead’s now 40-year old biography was coy. Lambert’s relationship with The Royal Ballet’s assoluta was evaded, saying only Lambert “had begun to fall in love with a dancer.” The identity of others was protected by asterisks.

Now, for anybody wanting to understand Lambert’s relationship with Margot Fonteyn – other than as her advisor in reading matter – Stephen Lloyd’s new biography adds little. Something of the trajectory of their relationship is hinted at in a letter from the Covent Garden archive, I think previously unpublished: Lambert asks Frederick Ashton to convince Fonteyn that he is not a “beast.”

This followed a house party to which Fonteyn and Lambert’s first wife, Flo, had in error both been invited. Ejected from the house, Flo waved her bottom in the air – and subsequently joined the Vic-Wells Ballet – suggesting she had more character than solely as a lookalike for Anna May Wong, the actress on whom Lambert was fixated. Well chosen photographs reveal just how physically similar all three women were, Fonteyn’s Chinese background being particularly pronounced then.

Lloyd has written widely on English composers and is meticulous in combing together many fragmentary impressions of Lambert. The book weighs over 1.5 kilos, 419 pages of small print, most heavily annotated in smaller print still, with a further 150 pages of appendices. (The footnotes have a life of their own. We learn Lambert’s Salome was seized by the Inland Revenue and scores abandoned by him in Holland in 1940 were recovered from Audrey Hepburn’s mother). Though informed by few original conversations with those who knew Lambert, Lloyd’s book is clearly a labour of love, most at home outlining the musical compositions. He fails, however, to bring the man, ever mercurial – described by Osbert Sitwell as eager not to miss anything – fully to life.

Typical of Lloyd’s approach is his chapter on Lambert’s experience – a 21-year old, scarcely out of the Royal College of Music – on composing Romeo and Juliet for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1926, a commission that Lambert secured ahead of William Walton, Diaghilev having taken a dislike to him. The first performances in France caused nearly as much sensation as Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps the decade previously, something to which the English media was largely oblivious, then preoccupied with the general strike.

Nor does Lloyd convey the premiere’s excitement, despite laying bare Diaghilev’s arbitrary and manipulative decision making – suspected of organising the first-night protests himself. Rather Lloyd carefully quotes already familiar accounts by Boris Kochno, Prokofiev (“a feeble sort of sub-Pulcinella”), Sergei Lifar, Alicia Nikitina and Lydia Sokolova. What Lambert though of it all is related mostly second hand.

And so it is with much of the book. Lambert’s protean personality is diminished by Lloyd’s dry use of the accounts of others. Lambert was pivotal in both the opera and ballet productions – The Sleeping Beauty and Purcell’s The Fairy Queen – that established the identity of the Covent Garden companies when the theatre reopened in 1946. At the time of Lambert’s death from undiagnosed diabetes, aged 46 just five years later, there was concern that a biography of so eminent a figure should be written while memories were still fresh.

But then the establishment discretion that cloaks the Royal Opera House took over – and Lambert largely dropped from view. Would that have concerned him? In Glasgow, (never his favourite tour destination, where audiences were noted for knocking-out their pipes on the orchestra rail during the quietest moments), Lambert was asked to provide his autobiography. He detailed eight-hour days at the piano, which required him to be 90 percent sober, something that was bad for his temper, bad for his “sex-mania.”

© Boydell & Brewer. (Click image for larger version)

The book is a mosaic of such fascinating vignettes and asides. We glimpse Lambert, a precocious child apparently telling an adult who praised his thick head of hair that it was due to his fertile brain. Or alone, at the end of a Littlehampton breakwater, attempting to conduct the sea. Or described by Michael Tippett, a year his junior, as the Royal College’s whizz kid. There too, Lambert’s tutor, Ralph Vaughan Williams recognised he could not be doctrinaire in teaching so prodigious a talent. Or how the Vic-Wells dancers were excluded from the official reception that followed the premiere of Checkmate in Paris (plus ça change as The Royal Ballet found on a return visit 50 years later, Lloyd omits). Or later, when a friend characterised Lambert as hardworking, hard living – and usually hard-up.

Elgar is quoted, querying why anybody would want to listen to opera in English. Lloyd captures too other figures now on the periphery of history. That celebrated, cultivated yet underrated artist and stage designer Charles Ricketts (whose fame rests on his D’Oyly Carte Gondoliers and Mikado in the 1920s) acted unofficially in loco parentis to Lambert (his father abandoned the family when Lambert was a teenager), and stimulated Lambert’s recognition of the inter-relationship of art forms. Ricketts too instilled in him a formative fascination with the Ballets Russes, only five years before Lambert became the first English composer to work for Diaghilev.

For ballet lovers, most interesting is the account of the Camargo Society and the birth of British ballet, that rather lost period post-Diaghilev and pre-Vic-Wells Ballet. The treasurer, John Maynard Keynes ensured some semblance of economic order and curbed the wilder ideas of his wife, Lydia Lopokova, for the society’s occasional performances. Its first, in October 1930, with Lambert conducting, was well received. Lambert, as a jobbing musician was also rehearsal pianist for Marie Rambert, for whom also he had conducted.

Recognising talent when she saw it, in typical cherry-picking style, Ninette de Valois recruited Lambert to orchestrate Mozart’s Les petits riens for her Vic-Wells group, the only time that Lambert would allow a Mozart score to be used for dance. He developed a strong friendship and working relationship with Ashton. Not only did the choreographer regard him as his musical mentor, he recognised that Lambert was an expert in painting, literature – everything. The foundations for what became The Royal Ballet were being laid.

Those foundations were not always strong. Dancers took their opportunities where they could. Anton Dolin appeared for a curtain call after the London premiere of Job at the Old Vic, not in Satan’s costume but clad in evening dress and patent shoes, ready for his next job of the evening, a revue at the Hippodrome. In its infancy, the Vic-Wells company of 18 dancers performed 12 programmes drawn from a repertoire of eight ballets. Today perhaps the closest parallel is Rambert (New York City Ballet having abandoned such fluid programming) but Lloyd typically does not point the comparison or any lessons for companies today.

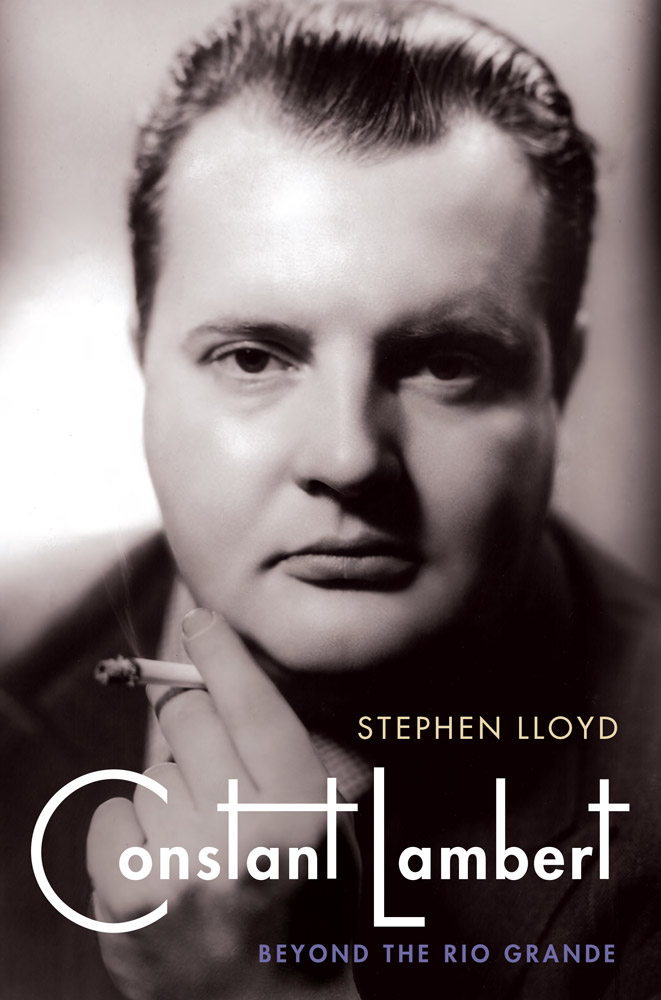

With the look of a young Orson Welles, Lambert stares out from the book’s cover, saturnine. A friend said you almost expected him to sprout horns. The force of Lambert’s personality and sense of humour is heard best in his letters and journalism. Hull is characterised as the Biarritz of the north. Toulon, despite the presence of Kochno and Christian Bérard, was judged to be free of pests. In Copenhagen, Lambert missed a company reception in favour of a Laurel and Hardy film. On one wartime journey, Lambert and Michael Ayrton, the artist and another underappreciated polymath, defaced the ceiling of a railway compartment with drawings of fish and cats from their perches in the luggage racks.

Less happily Ayrton produced portraits of Lambert in 1951, when the composer, drinking excessively, was struggling to complete Tiresias. Indeed, some of it was written in the Nag’s Head across the street from the Covent Garden stage door. Ayrton depicts Lambert’s bloated face with brutal honesty. Six weeks later he was dead. Although Tiresias prompted as much furore as Romeo and Juliet 25 years earlier, Lloyd makes clear that not all reviews were hostile. Tiresias, for which Lambert was composer and scenarist, was an overblown dose of sex, sexuality and copulating snakes – incredibly chosen for a royal gala during the Festival of Britain. The gender bending title role, danced jointly by Fonteyn and Michael Somes, provides great scope for analysis but typically Lloyd is purely descriptive.

Tiresias prompted Richard Buckle, The Observer critic, to write his infamous ‘Three Blind Mice’ review. De Valois was too busy, Ashton too inclined to compromise and Lambert too concerned with music (the waft of alcoholism hovers in the air) to notice what was wrong. According to Buckle it lacked logic, form, dramatic tension, human interest, characterisation, sincerity and beauty. Again, plus ça change.

Tiresias had a couple of revivals after Lambert’s death, with Fonteyn dancing as if possessed – but not after her marriage to Tito de Arias. A member of the company, not interviewed here, believes this was less to do with the ballet itself – dramatic in an obvious way, shocking for its time – than with Arias’ influence in suppressing anything of Lambert’s associated with his wife. Establishment discretion.

So – who is Lambert, what is he? Did he spread himself too thinly as composer, conductor, arranger, librettist, writer, mentor – and bon viveur – as his detractors claim? It is not a question that would have detained him. Lambert’s work on making The Fairy Queen performable for modern audiences occupied him fully for six months but he said his work was done for the benefit of others. Writing of Liszt in one of his book reviews, Lambert said, “His greatness lay in his variety of purpose, in the way he squandered his gifts, in the way he would drop his own work to put his burning enthusiasm to the service of others.”

Lambert accepted that as a conductor of ballet he was the last person that reviewers would notice. Those who knew Lambert had no doubts about his talents. Fonteyn was terse as a headstone, “that brilliant composer, conductor and champion of ballet.” Bliss gives more a sense of the mean, “a sensitive composer, a brilliant pianist, an acid critic.” The pity is that such figures are no longer alive for Lloyd to interview first hand. Then we might have had a biography that more fully animates the maverick that was Constant Lambert.

You must be logged in to post a comment.