© Kenneth Archer. (Click image for larger version)

Millicent Hodson and Kenneth Archer first put their reconstruction of “The Rite of Spring” on Rio de Janeiro Ballet in 1995. This year they went back to put it on again – this is what happened…

www.hodsonarcher.com

www.theatromunicipal.rj.gov.br

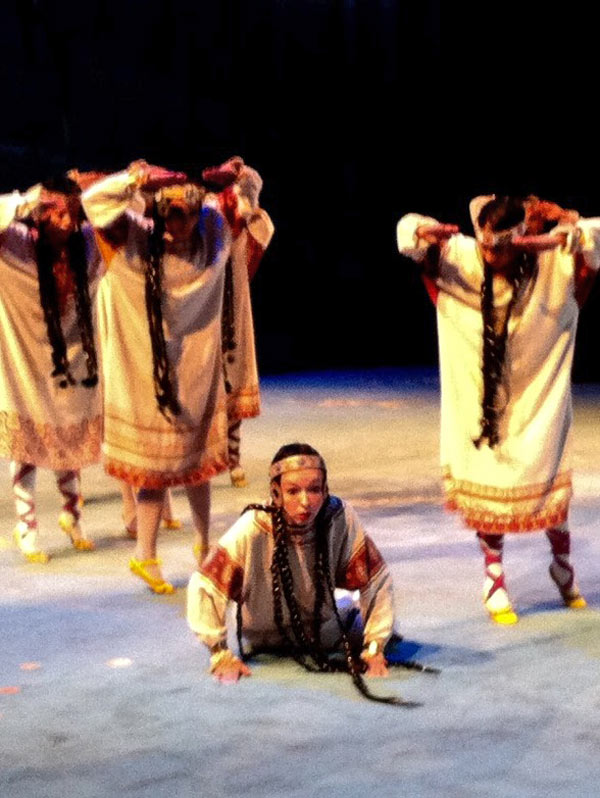

Precise but passionate, dancers in Rio de Janeiro recently performed a Rite of our dreams when we restaged the 1913 reconstruction of Le Sacre du Printemps at the city’s finely preserved Theatro Municipal, an Art Nouveau monument from 1910, with all its original mosaics, golden proscenium and capacious corridors ever open to the soft Brazilian breeze.

© Kenneth Archer. (Click image for larger version)

We first did the production in the mid 1990s then revived it in 2013 for the 100th anniversary of the Stravinsky/Roerich/Nijinsky ballet. That meant dancers who were with us at the outset, then fledglings, were seniors in the company by the time of the centenary. Now in 2015 some of them had moved into new careers, replaced by young professionals and eager students just out of the Municipal’s ballet school. The reconstruction benefits from this generational continuity. A Chosen One from our staging in 1996, Paula Passos, presently dances the role of the Old Woman of 300 Years. She still has the magnificent jump that served the climactic solo so well and which makes sense of how the witch, knowing the secrets of the earth, can teach men in the tribe divination via mountain goat jumps – knees to their ribs – over her scattered twigs.

Nijinsky himself danced at the Municipal in 1913. Around the corner from the theatre, Vaslav bought Romola’s engagement ring for their forthcoming marriage in Buenos Aires, leading Diaghilev to fire him from the Ballets Russes. Later, in 1916-1917, Nijinsky was brought out of house arrest in Hungary during the first World War to direct a company tour of the Americas in Diaghilev’s absence. Once again he danced at the Municipal. According to Romola’s biography, they so loved Rio de Janeiro, especially the lushly tropical district of their hotel in Santa Teresa, that Nijinsky wanted to start his school there, combining dance and the arts with religion and philosophy. His spirit persists in the Municipal repertoire with two roles created for him by Mikhail Fokine, Le Spectre de la Rose which we saw in 2013 and Les Sylphides which was on this year’s programme. Both were coached by the much esteemed Tatiana Leskova who came to Brazil with De Basil’s Ballets Russes in the 1940’s, stayed to get married, perform at the Municipal and enrich it with Russia’s ballet heritage.

© Adriano Barros. (Click image for larger version)

The Rite Context

Ritual is just beneath the surface of daily life in Rio, not only because of the rich racial mix of Africa and Europe with indigenous cultures of the Amazon and beyond. It also has to do with the feeling for nature that flows without effort, it seems, from a land of eternal summer, with colour and rhythm everywhere, from street graffiti to rehearsal garb. When we quoted to the cast what Bronislava Nijinska, the choreographer’s sister, said, that the Chosen One dances herself to death to save the earth, they raised issues of deforestation, urban crawl and the dangers of globalisation bringing them MacDonald’s to replace the traditional juice bars and coconut carts on every corner.

© Kenneth Archer.

These dancers instinctively understand shamanic iconography, even though Roerich’s Slavic imagery may seem continents and centuries away. With no prompting from us, the dancers formed a ritual circle before performances as the Old Woman, Paula, now retraining as a “BodyTalk” colour therapist, took them through mantras and movements to dispel negativity and radiate energy to the audience. Reversing rehearsal procedure, they swept us into the circle.

When we discussed how Nijinsky had apparently transferred Roerich’s costume motifs to the ground patterns of the choreography, the dancers and rehearsal staff took it as given and told us about ceremonies in Bahia, way up in the far northeast of Brazil, where similar correspondences occur in ritual dance and design. Some of this Millicent had learned, during her New York dance years, when she studied folkloric forms with Mercedes Baptista, whose photo we were delighted to discover on a studio wall of the Municipal school. This year, once we got onstage with costumes, Kenneth spoke again to the dancers (despite technical time pressures) about the motifs on their garments and accessories, trying to keep fresh and relevant all the shamanic connections.

With this group we organised a Rite event at the Municipal school.

© Luana Mela. (Click image for larger version)

Turning Inward

After supervising the pre-season invitational gala, we had to leave for London prior to the public premiere of the 2015 production, the best yet, we felt. But on the first night, “Sagraçao” (as Sacre is rendered in Portuguese), had a standing ovation, we are told, by the whole theatre. Dance seeps into the bones over time and a ballet can change in depth with cumulative casts and years. In most companies the reconstructed Rite gets better with age as performers internalise its stylistic demands and emotional significance. Even still, Rio gives something extra to the reconstructed Rite, what we described to ourselves as a rainforest of rhythmic surety, commitment and suspended disbelief.

© Marcella Gil. (Click image for larger version)

It was (and often is) a turbulent time in Brazil. There were demonstrations in Rio about government corruption involving the corporate giant, Petrobras, with calls for impeachment of the country’s first woman president, Dilma Rousseff. Some of our dancers and staff declared that it was time for her to leave the presidency. Others felt that corruption generally, and this instance in particular, are problems she inherited from previous leaders so she should remain in power. Politics seem ever present in the practicalities of Brazilian life; our pre-general rehearsal provides a dramatic example.

We were shocked to see dancers destabilised all over the stage. How could this happen? They were carefully rehearsed and ready the day before. Of course, there are many acts of falling in The Rite. The third scene features a big unison fall, Nijinsky’s modernist take on the singular group collapse that Mikhail Fokine used for Kostchei’s spell in Firebird. But in The Rite, as we interpreted the surviving clues, everyone hits the ground in slow motion, a kind of Futurist fracturing of time and movement. Here it is not the work of a wizard but the pull of gravity on archaic souls, rendered as modern sculpture on almost fifty bodies at once. And there are other crucial falls in this ballet, like the witch’s fall that scatters her twigs and the Small Maidens’ stretch on the grass to distract men from fighting in Act I. And in Act II there are the stumbling topples that reveal which Maiden will dance herself to death and the other Maidens’ merciless pratfalls, flat on the face, to evoke tribal ancestors from the depths of the earth. However, what we saw at the pre-general were not these carefully crafted moments of climax but random accidents that eroded the ritual discipline of the choreography.

© Kenneth Archer. (Click image for larger version)

At the pre-general it transpired that the ground cover, the massive expanse of green canvas that is already a challenge for dancers used to Mylar floors, had not been fixed tightly. What had been perfect through all the Rite performances two decades ago as well as two years ago, went horribly wrong. Why? Afterwards we learned that the entire technical staff of the theatre, from costumiers to electricians, had gathered onstage before our pre-general to debate the impeachment issue, a debate so heated they did not finish preparations in time for the orchestra’s scheduled start.

Brazil is right out there in the world just now, highly visible as a BRIC nation and host of the last World Cup and the next Olympics. Yet it evidently has a great need to turn inward and solve massive problems of infrastructure. The economic miracle did not benefit everyone. The rich got richer, and the poor, even those in the “favela” shanty towns that surround Rio, had boosts from federal and local programmes. But the middle sector of society, from dental workers to dancers, has had no salary rise in a dozen years. So tensions erupt in all kinds of demonstrations. Yet the whole country, and the carnival city of Rio especially, is ever a kaleidoscope of colour and motion, where The Rite looks and feels quite at home, appreciated by a diverse audience. During studio work on the ballet, a rehearsal assistant, dance scribe Paulo Arguellos, held aloft the cover of Inteligência magazine, featuring the president in trouser suit and loafers, in an inverted posture identical to Sagraçao. Some urged us to call in Madame Rousseff for an audition at the Municipal, thinking her talents could be better used in The Rite than in conflicts over Petrobras.

© Kenneth Archer. (Click image for larger version)

Keeping Still

The Rite of Spring is a noisy ballet, as evidenced by a story dancers love to hear about a pilgrimage, way back when Millicent was a student, to find the surviving instrumentalist, Louis Speyer, from the 1913 ballet’s riotous premiere. She went to his home in Boston, asking what he could tell her about the choreography of The Rite. “My dear”, he sighed, “I didn’t see a thing, as I was in the pit, you know, and my back was to the stage”. She mentioned her long journey, prodding him to remember something. “Well”, he paused, “they made a lot of noise”. “You mean the repetitive stamping and clapping”, she replied. “Yes”, he agreed, “but also all that beating with their hands on themselves and on the floor”. His remark made us aware of the body percussion in the first Rite, which reaches its peak in the “Simultaneous Solos” of all the dancers at the end of Act I, probably what Speyer recalled.

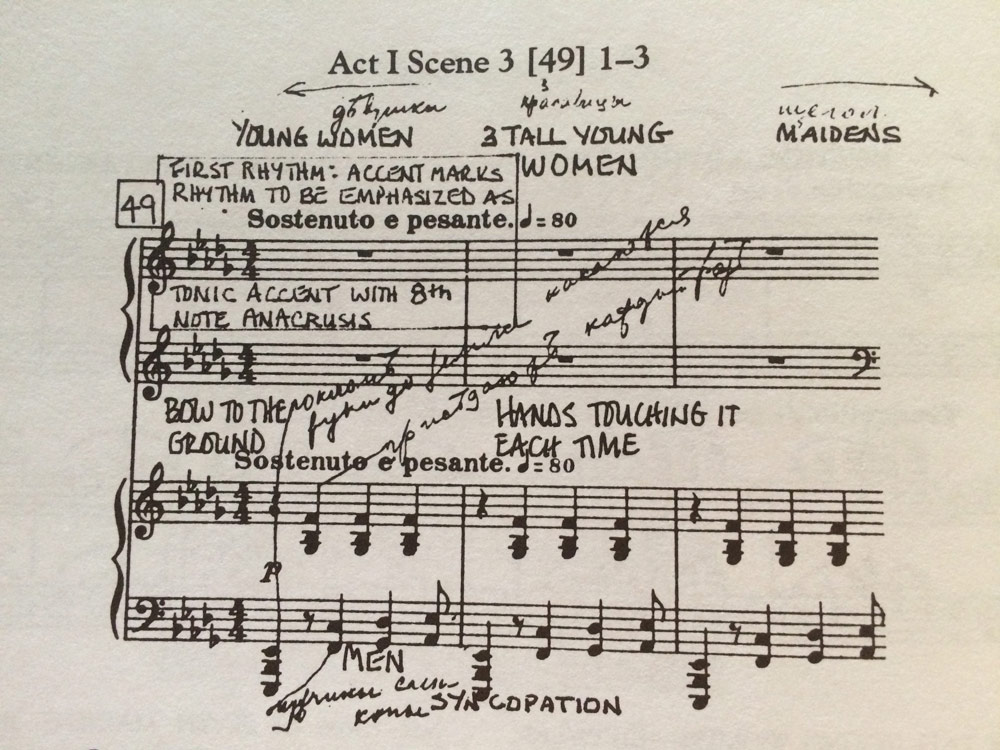

But there are percussive bursts throughout, such as the syncopated beats on the ground as the men enter in a large pack for “Spring Rounds”. Nijinsky’s assistant, Marie Rambert, wrote in the notes on her piano score that, for the entrance, they syncopate the second note of each 4/4 bar. They start in a still pose, rooted, then hit the ground with flat hands on the “and” after the two, stay attached to the ground for the three, suddenly lift their hands as if charged by the earth on the “and“ of the three, and finally rise and change direction on the “and” of the four.

© Kenneth Archer. (Click image for larger version)

© Rambert Archive. (Click image for larger version)

Precision is everything, both the sudden thud of hands at the same time and the bas-relief stillness of bodies between movements. Keeping still is as vital as hitting the beat. The Rio dancers, throughout the ballet, found the stillness of The Rite. It requires sudden total stops of body and mind, gravity sensed from the inside, as French critic Jacques Rivière documented in 1913.

© Kenneth Archer. (Click image for larger version)

Our maestro, Javier Logioia Orbe, was fascinated by this intervention into the soundscape of the music. He told his players that the dancers comprised “another department of the orchestra” and organised a session during stage rehearsals to be sure that everyone was exactly together on the beats so that the syncopations would be crystal clear.

It is a truism that Brazil is mad about football. Games are played on the beach at all hours, intense conversations flare up on the subject, cafes and restaurants are packed with spectators for TV transmissions of big matches. We even noticed that moves from the field have been integrated into gestures of daily life. In fact, at a moment in The Rite when Rambert says the Maidens are supposed to turn “troubled on the spot”, preventing the Chosen One from escaping, one dancer’s shuffling made us all think of a goalkeeper on guard. So pervasive is the football culture that, when Millicent blew a whistle to get the tribes in order, everyone was startled for a moment then broke into cheers.

© Barbara Lima. (Click image for larger version)

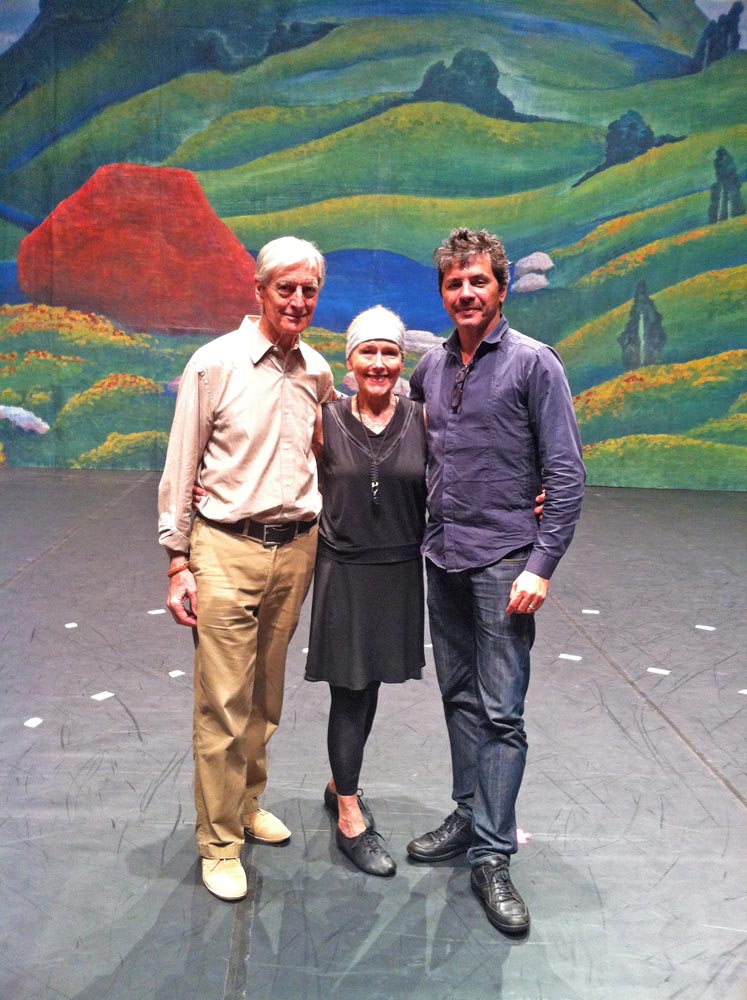

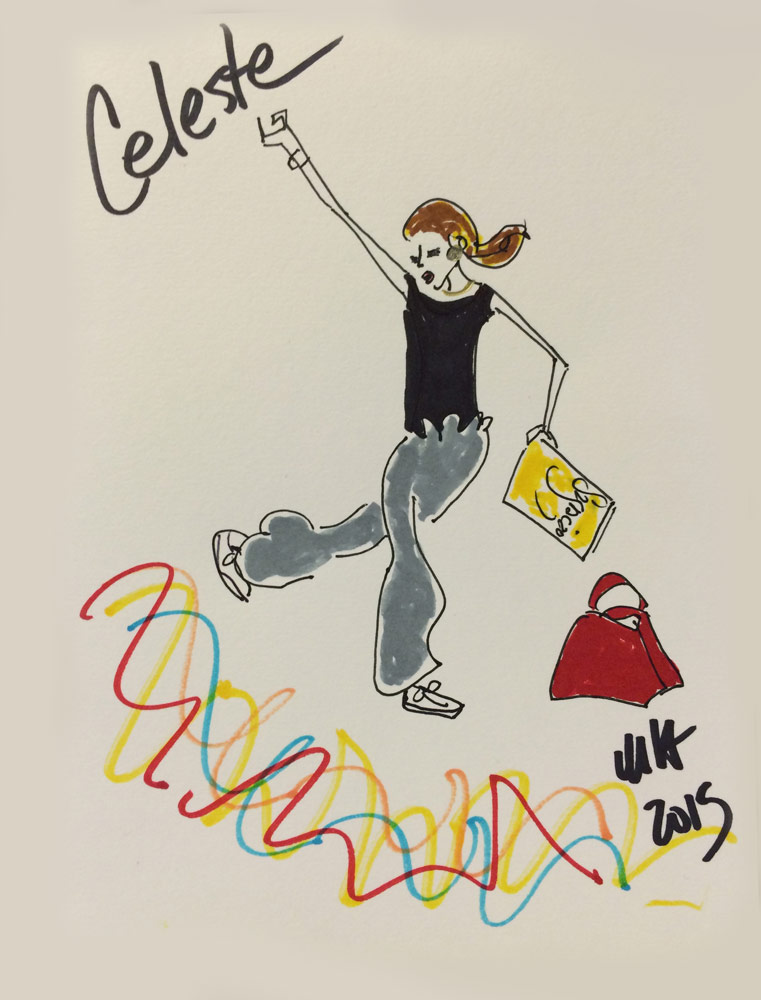

Maybe football is a model for how things work in Rio. We found a high level of teamwork in the studio with dancers and staff, especially our rehearsal squad of repetiteurs led by Celeste Lima, accompanists headed by Gelton Galvao, the scribe Arguellos, who made charts for the kaleidoscopic patterns in the choreography and Benesh notator Cristina Cabral. Ballet director, Sergio Lobato, visited rehearsals regularly to watch our progress, as did Maestro Logioia, and even director of the Municipal, Emilio Kalil, who had first invited us to Rio on behalf of Jean-Yves Lormeau, then ballet director, commuting back and forth to Paris where he was a star at the Opéra. He had seen us staging The Rite there in the early 1990’s and told us he felt dancers in Brazil would be enriched by the way we taught history through the choreography and costumes of the reconstructed Rite.

© Millicent Hodson. (Click image for larger version)

Two decades later we understand that they have enriched us, at least in equal measure, and not just us. When we first did the ballet there in 1996, there was a moment that really astonished us. It was when the momentum from pulling in the “Tug of War” sets everyone spinning and ends in an abrupt jump with hardly time to land before a mass running pattern in jagged rhythms. This jump had caused a lot of rehearsal headaches ever since 1913. But the Brazilians simply exploded with joy and ran right on the mark. Henceforth we called this movement, “the joyful jump” and told other companies how the Rio dancers did it. In St. Petersburg the Mariinsky artists took to shouting out “Rio!” when doing the jump. In many ways the Municipal has left its imprint on the work.

Friday afternoon rehearsals turned into a kind of celebration, so weary were we all and ready for the weekend. On one occasion we invited a local Tai chi master, Eduardo Molon, with whom Millicent trained during our stay in Rio. He joined our circle at the end of rehearsal and we did with the dancers a few of the ancient Chinese forms. Another Friday we were delighted by a studio visit of the dancer Akram Khan, a fellow Londoner, busy with technicals for his performance that night at the Municipal of his kathak/flamenco duet, Torobaka with Israel Galvan from Madrid. Khan had performed his own Sacre in Rio last year and told the dancers that he still found the music “scary”.

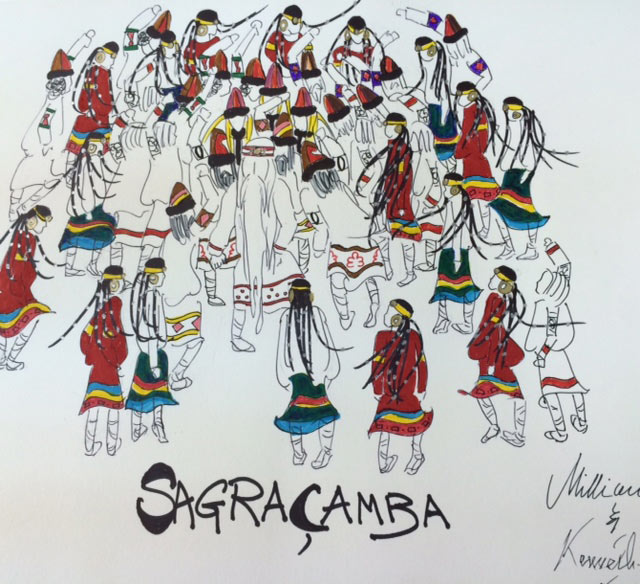

An unforgettable end of the week treat was a trick we played on the dancers. At the close of Act I is a stamping passage when the tribes close in around the Sage. “ONE two, one-and-two, one TWO, one-and-two”, etc. We all sing Stravinsky’s shifting accents as we move toward centre. The syncopations feel so Latin that dancers are tempted to swing their hips, especially Brazilians, who recognize something of the Samba in this climax to what is meant to be a Slavic rite. So we plotted with our repetiteur César and the accompanist Gelton to supplant (with no warning) the Sagraçao music with a bit of real Samba. The dancers were galvanized into fast footwork and wild hip gyrations. They wrapped the Sage in a Brazilian flag, demanded to do it again, and danced their way out the studio door, calling this new variation the “Sagraçamba”.

Drawing © Millicent Hodson

© Kenneth Archer. (Click image for larger version)

You must be logged in to post a comment.