© Jamie Kraus for Jacobs Pillow 2014. (Click image for larger version)

Fall For Dance Festival 2015

Program 1

Miami City Ballet: Allegro Brillante

Doug Elkins Choreography, Etc.: Hapless Bizarre

L.A. Dance Project: Murder Ballades

Che Malambo: Malambo

Program 2

La Compagnie Hervé Koubi: What The Day Owes to the Night

Steven McRae: Czardas

Pam Tanowitz: One Last Good Chance

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater: Four Corners

New York, City Center

1, 2 October 2015

nycitycenter.org

Malambo!

For twelve years, the Fall for Dance festival has been going strong, and one can see why. No other dance series offer such an expansive, egalitarian and uncomplicated glimpse of what’s going on in dance, not just in New York, but around the country and, at least to a certain extent, around the world. (And all at the unbeatable price of $15.) The offerings are selective, of course, but often they feel random. And that’s a compliment. Among other things, it allows for an element of surprise.

During the first two programs of the festival’s current edition, surprise came in the form of two works featuring battalions of men, one rambunctious, the other deeply serious, almost meditative. The first was danced by Che Malambo, a male troupe from Argentina who brought an updated and slightly hyped-up version of the indigenous gaucho dance malambo. They were the closing act on the first program of the festival. The other, which opened the second program, was Compagnie Hervé Koubi, dancing What the Day Owes to the Night, a meditation on maleness by the Algerian-French choreographer Koubi. Both were spectacular, each in its own way.

© Christopher Duggan courtesy of Jacobs Pillow 2014. (Click image for larger version)

Malambo is an interesting form, born in the countryside – the legendary pampas – where, in their free time, men competed with each other by showing off their skill at zapateado, or percussive footwork. Usually performed in loose-fitting trousers and boots, malambo involves striking the floor with every surface of the foot, particularly the sides, with the ankle at an angle. Meanwhile, the hips swivel, creating a loose-waisted counterpoint to the pounding feet. This combination sets it apart from flamenco, tap or Irish step-dancing, its nearest cousins. In another trick, the dancers strike the floor in percussive patterns with boleadoras, ropes with hard appendages at the end, originally used for hunting. A stage full of boleadoras flying at full speed is quite a sight. The guys of Che Malambo sex things up by dressing like modern flamenco dancers, in tight black jeans and vests, with the requisite wet hair. They grunt and yelp and twist their faces in sexy moues. It’s all a little heavy-handed, and the guys seem to know it. Still, when was the last time you saw malambo in New York?

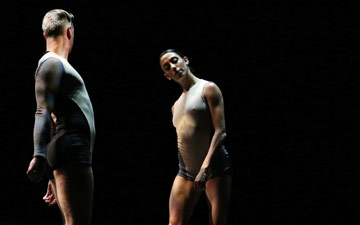

What the Day Owes to the Night was surprising in an altogether different way. This troupe of twelve bare-chested men in white trousers was like a religious brotherhood devoted to tumbling, acrobatics and martial arts. They spun, they flew, they glided. On several occasions, a man was thrown so high that the audience gasped. Others did backflips, in slow motion; two spun on their heads like tops, for a very long time. One seemed to hover in the air upside down at the top of a flip. All this was done in a quiet, laborious, almost devotional manner, as light sculpted the men’s muscular bodies. (Who knew such burly men could move with such grace?) At first they moved in silence, then they were accompanied by a piece for the oud by the Egyptian composer Hamza El Din (recorded). Then, a Bach chorus. The choice of Bach was an obvious grab at spiritual transcendence, but, truth be told, the dramatic, quasi-religious tone was effective.

© Daniel Azoulay. (Click image for larger version)

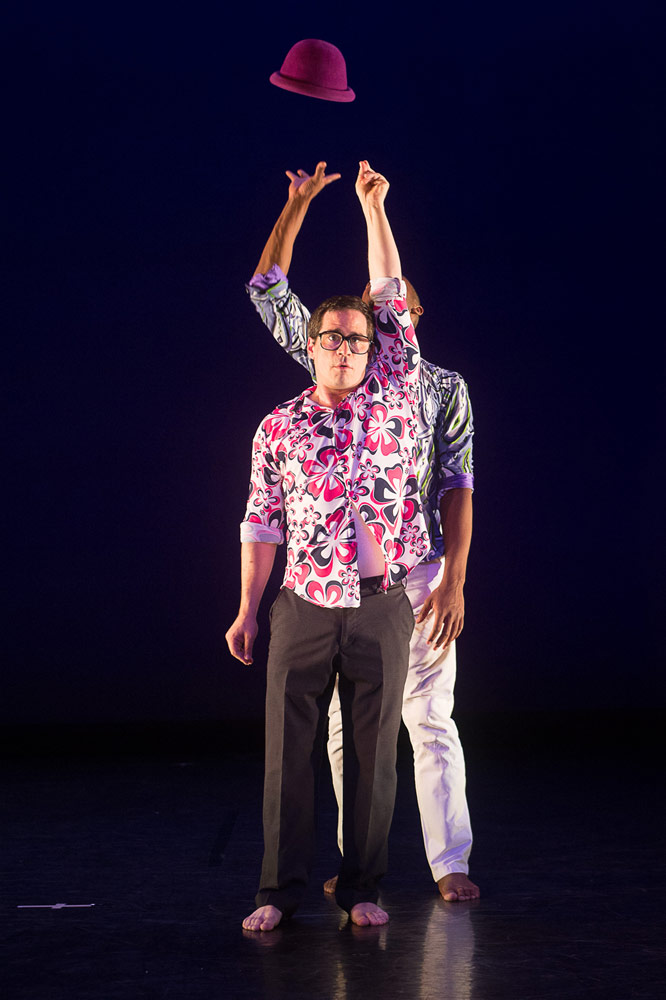

As usual, the two programs offered a little bit of everything. On the first night, Miami City Ballet gave a buoyant, warm, joyful rendition of George Balanchine’s Allegro Brillante, with a radiant Patricia Delgado at its center, partnered by a gallant and capable Renan Cerdeiro. (Too bad the recording was so tinny.) Doug Elkins’ ensemble performed an overly cutesy but well-danced jukebox suite, Hapless Bizarre, about an awkward everyman (Mark Gindick) looking for love amongst a clan of cool-cats. (He finds it in the end.) Elkins’ choreography has a sensual slinkiness, though the partnering can sometimes feel too much like problem-solving. L.A. Dance Project, Benjamin Millepied’s other outfit (besides the Paris Opera Ballet) brought Justin Peck’s Murder Ballades, a savvy, youthful ballet in sneakers set to folk-inflected music by Bryce Dessner. The most spectacular aspect may be its grainy, color-smeared backdrop, by Sterling Ruby, but the choreography also has its memorable passages, including a driving, almost square-dance-like section and a solo of despair for Julia Eichten vaguely reminiscent of the cowgirl’s lament in Agnes de Mille’s Rodeo. It’s a very American piece, in the best sense of the word: athletic (so much running!), spacious, off-kilter, free.

© Rose Eichenbaum. (Click image for larger version)

The second program was just as varied. Pam Tanowitz, a New York-based choreographer, was commissioned by the festival to create a new work, and came up with One Last Good Chance, a trio for two dancers from American Ballet Theatre and one from ABT’s studio company. Tanowitz used a quartet by the avant-garde composer, Greg Saunier, consisting mainly of sawing violins and long rests – it must be hell to count – played at the back of the stage by the lively Flux Quartet. The stage was bare, except for an illuminated doorway at the rear, a passageway to an inviting, brightly-lit space. The costumes, by Reid Bartelme, were really handsome: crisp white with black, asymmetrical geometric shapes, in clean, flattering shapes.

As with previous efforts, Tanowitz’s choreography for One Last Good Chance was like a molecular deconstruction of ballet technique. A preparation for a pirouette never became a pirouette; two dancers (Devon Teuscher and Tyler Maloney) executed a spotting exercise, pivoting while keeping their gaze forward as if staring into a mirror. (Both were marvelously objective in their delivery.) Another dancer (Calvin Royal III) did a few beautifully-executed brisés in a corner while holding a hand to his shoulder, just so. The two men picked Teuscher up in fourth position and carried her to a different part of the stage, still in fourth position. It was either witty or completely daft, depending on your point of view.

A short, clever solo by the Royal Ballet principal, Steven McRae, combined ballet – super fast chaînés and pirouettes – with tap-dancing, all set to a Hungarian czardas. The closer was Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in Ronald K. Brown’s Four Corners. It’s a mesmerizing work in Brown’s signature style, which combines West African dance, samba and club dance. The movement is full and rich, particularly for the back and arms; you can almost feel it in your own body. The Ailey dancers, led by the heroically-proportioned Jamar Roberts – how can such a large man project such sweetness? –, Linda Celeste Sims, and Belen Pereryra, danced it with silken smoothness and deep, unstinting power. They looked like they could keep dancing all night long. And no-one would have complained.

I decided not to buy tickets this year, feeling I had enough (or too much) going on as it is, so I’m glad for your report. I’d especially like to have seen Murder Ballades, since I still have a thing for sneaker ballets, and I’m curious about McRae’s ballet-tap-czardas solo, but judging from your descriptions I’d have loved most or all of these two programs.

[…] City Center, Fall for Dance kicked off with two varied programs, each containing a surprise. See my review […]