© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The Royal Ballet

The Cellist (★★★✰✰), Dances at a Gathering (★★★★✰)

★★★✰✰

London, Royal Opera House

17 February 2020

Gallery of pictures by Foteini Christofilopoulou

www.roh.org.uk

In The Cellist, Cathy Marston has taken on a challenging subject for her first commission for the Royal Opera House stage: the real-life story of a much-loved musician, Jacqueline Du Pré, whose career was cut short by multiple sclerosis at 28 and who died at the age of 42. Her sister and brother are still alive and her former husband, Daniel Barenboim, continues to be a formidable musical force.

Marston, who calls her leading dancer simply The Cellist, has not attempted to depict a detailed biography of Du Pré. The problem she has set herself is that the medium of dance is a paradoxical choice to portray a cello player. A dancer’s highly trained body is already an instrument for interpreting music. As The Cellist, Lauren Cuthbertson needs another physical instrument through which to convey what music means to her. She adopts a splay-kneed posture with her feet flat on the floor, bowing away at Marcelino Sambé as her cello. We have to accept that he literally carries her away, embodying her love for the music she makes through him.

The intangible power of music is therefore made corporeal. It’s even given solid form in vinyl discs: characters brandish the LP records Du Pré recorded and that live on after her (though largely superseded by digital streaming). Here is the contradiction at the heart of Marston’s ballet: she is both an over-literal storyteller and a daringly imaginative choreographer. She has exceptional interpreters in Sambé and Cuthbertson, who persuade us that a musical instrument can be a sentient being, a mentor, companion and lover.

© Bill Cooper, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The ballet is framed as the elegiac recall of the cello. In the darkness, Sambé emerges from the instrument case to the opening notes of Elgar’s Cello Concerto. Unplayed, he watches as young Jackie (Emma Lucano from the Royal Ballet School) is enchanted by first hearing the sound of a cello, via an LP record offered by her mother (Kristen McNally). We see the concerns of her family as she finds her vocation, striving to embrace Sambé’s upraised arm as the fingerboard of a full-size cello. Her child’s cardigan then reappears on Cuthbertson as adolescent Jackie, precociously besotted with her obedient instrument as she sways around him.

Her mother’s teaching is usurped by male instructors, led by Gary Avis in a cameo role. Meanwhile, the corps de ballet, described as a chorus of narrators, transform themselves from schoolchildren to concert-goers, orchestral players and musical instruments as her professional career takes off. They also shift elements of the curved wooden set, designed by Hildegard Bechtler to suggest a home, a concert hall, a recording studio, a sinister void. The chorus bends and bows as the conductor (Matthew Ball as Daniel Barenboim) dances onto the podium to take charge of the orchestra and solo cellist.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Philip Feeney’s cinematic score, referencing Du Pré’s repertoire along with his own composition, here cedes place to Elgar’s Cello Concerto. Hetty Snell is the cello soloist in the pit with the Royal Opera House Orchestra, conducted by Andrea Molino. The simulated orchestra on stage disappears discreetly as Cuthbertson’s Jackie falls for Ball as a dominating Svengali figure. Sambé as her Stradivarius cello encourages their relationship in an intertwined trio – surely a first in ballet for a woman, a man and a musical instrument.

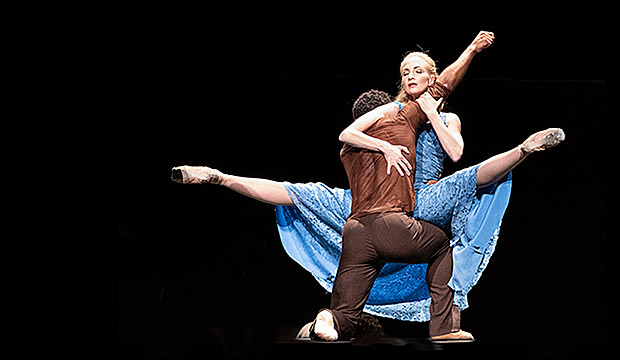

Marston’s intimate, swirling choreography to Elgar’s music conveys the ecstasy of first love, Cuthbertson’s soaring leg echoing Sambé’s cello neck arm. This wordless expression of emotion is what dance can do so well – until Marston jolts into literalism by having Ball play Cuthbertson’s outstretched body like a keyboard. Barenboim was of course a pianist, as Ball demonstrates when three young men bound in to play. Luca Acri, Paul Kay and Joseph Sissens are presumably the other members for Schubert’s Trout Quintet, memorably filmed in 1969 by Christopher Nupen: Itzhak Perlman, Zubin Mehta and Pinchas Zukerman, young virtuosi, with Du Pré in her passionate prime among them.

The narrative tempo becomes burdened with too many scenes. A Jewish wedding ceremony, with Téo Dubreuil as the rabbi, is followed by an Israeli folk dance for the celebrants. The happy couple are besieged by enthusiasts waving their LP souvenirs of best-selling recordings. A marital pas de deux has Cuthbertson straddling Ball’s waist with the aid of a revolving stool. Is she playing him? They take it in turns to bear each other’s weight, which looks ungainly rather than egalitarian. The marriage flounders as Ball’s conductor appears to be the instigator of the punishing touring schedule that damages Jackie’s mental and physical health. The busy corps dash about carrying cello cases, constantly moving the walls of the set to dizzying effect.

Cuthbertson crashes to the ground, nudged by Sambé like a dog trying to save its owner-companion. Compassionately, he lifts her upside-down, her knees bent and feet flexed as if sitting behind her cello or in a wheelchair. Her hand trembles, a sympton of her illness: Feeney’s music distorts, as Adam’s does when Giselle loses her mind. Jackie is reduced to a child-like dependency (that cardigan again) in the bosom of her family. The chorus of narrators suffers along with her as she is passed between doctors and consultants. Instead of keeping the focus entirely on her, Marston has the corps pose distractingly as lamps, doors and other bits of furniture.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

In a poignant scene, Jackie appears to be in remission. She starts a public recital but can’t manage the weight of the cello. She turns on Sambé in anger, fighting him as he tries to calm her, hurt by her rejection. He has to acknowledge defeat, kissing her hand as he retreats. Marston’s treatment of Jackie’s debilitating disease is sensitively done, as Cuthbertson loses her ability to dance as well as play. She recalls her childhood joy in discovering the cello’s music. Two tall men lift her as if in a wheelchair. Sambé lies over her and Ball bids them both farewell. Sambé spins as darkness falls: he is both a vinyl recording that lives on, and an antique cello that will be brought back to life again.

Sambé’s impressive achievement is to make his unlikely role believable. He dances with dignity as well as powerful fluency, transforming himself from a submissive instrument into an expressive shape-maker, not entirely human, though with palpable emotions. Cuthbertson imbues her role with vigorous abandon until she is cut down by a disease she cannot conquer. Marston hasn’t given her a distinctive vocabulary of ballet steps (although she’s on pointe), so she relies on her physicality to convey her feelings. Ball’s Barenboim is a handsome cypher with an impressive gestural presence but no inner life.

The Cellist is essentially a chamber piece, with lovely, inventive duets and trios for the three principal characters. Its structure is overblown with too many minor characters whose significance isn’t examined, and an over-busy corps. Marston likes to deploy numerous dancers in her works for large companies, using the corps de ballet to provide a sense of place, a social setting, elements of nature or to serve as props. Here they are required to be too many things, protracting the story-telling and leaving little space for the climactic scenes between the cellist and the musical instrument through which she celebrated her talent.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The Cellist is preceded in the double bill by Dances at a Gathering, the Jerome Robbins ballet that replaced a scheduled premiere by Liam Scarlett. Marston’s premiere has therefore received the media attention that would otherwise have been shared with Scarlett’s new ballet, a version of Oklahoma. In its stead, Dances at a Gathering proves a fine counterpoint to The Cellist because it is simply about the bliss of dancing to music. Ten dancers, not all of them couples, come and go to Chopin piano studies within an airy space. It’s somewhere they know, or knew, well – maybe Chopin’s Polish homeland or a rehearsal studio. The first dancer on stage, a man in brown (Alexander Campbell) drifts in with his back to the audience and touches base as though remembering a place he once danced. Then the piano, played by Robert Clark, takes over and Campbell becomes a lively young dancer once again. He will make the same nostalgic gesture at the conclusion of the ballet.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The 60 minutes or so that follow are filled with contrasting moods and impulses for dancing. A carefree young couple, Francesca Hayward and William Bracewell, scarcely touch until he carries her off. They are succeeded by a pair of older friends or lovers, Marianela Nunez and Federico Bonelli, who waltz intimately together, buoyed by lots of lifts. Robbins juxtaposes duets for different partners with dances for uneven numbers, so that someone is briefly left out of trios or quintets. A speedy soloist, Yasmine Naghdi, seems happy to be on her own. Laura Morera tries to engage passing men in conversation and is ignored – they know she’ll hold them up, but she’s unfazed by their pretended indifference.

She has a solo that comes as a palate cleanser after a duet for two men, Bonelli and Campbell, who size each other up competitively. Morera is the only member of the cast who really seems to improvise to the music: ‘I could do this, or maybe this – wherever it takes me.’ Others, Nunez in particular, phrase their variations beautifully, already inside the music.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Sometimes dancers acknowledge the audience, posing as if for photographs, or showing off how fast they can move or how high they can jump. At other times, they dance for and with each other. There are never more than six on stage at the same time, until the wistful final number to a Chopin Nocturne brings on all ten, musing together. They watch the passing of a cloud or perhaps a flock of evening birds, knowing that their generation of dancers will inevitably be overtaken by time. Before the end of the hour-long ballet, some spectators may have tired of the outpouring of dances – but which ones could Robbins possibly have cut?

You must be logged in to post a comment.