© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

09 May – All Robbins No. 2: The Goldberg Variations, Les Noces

10 May – Tribute to Robbins: The Four Seasons, Circus Polka, A Suite of Dances, Easy, Something to Dance About

★★★★✰

New York, David H. Koch Theater

9, 10 May 2018

www.nycballet.com

davidhkochtheater.com

Robbins Remix

Not many choreographers can sustain a full program of their works, let alone a whole festival. But Jerome Robbins can, as was already evident ten years ago, when New York City Ballet presented 33 of his ballets in one blockbuster season. This years’ centenary celebration is somewhat smaller, with “only” 20 ballets; they fill 5 programs, to which the company has added a tribute by Justin Peck and a medley of Robbins’ Broadway numbers (in my opinion, the least effective element in the festival). They are more than enough to give a sense of this choreographer’s breadth, theatrical savvy, stylistic curiosities, and, perhaps most unique of all, his ability to present dancers as human beings onstage.

After a program comprising 3 ballets set to music by Leonard Bernstein, I caught one made up of just two works: The Goldberg Variations, from 1971, and Les Noces from 1965. And after that one, another, lighter lineup: The Four Seasons, a showpiece set to Verdi ballet music (1979); Circus Polka, for a bunch of little girls from the School of American Ballet (1972) – predictably adorable; his Suite of Dances, made for Baryshnikov in 1994; plus Justin Peck’s Easy; and the aforementioned medley. All are recognizable as creations by the same master, and yet all are distinct and memorable in their own ways. You can’t help but be amazed by Robbins’ constant effort to stretch himself and at the same time, by his sure touch, even when, as in Les Noces, an experiment is not completely successful.

The desire to experiment at times pushed him to excess (as in Goldberg Variations) or to hollowness (as in Les Noces). In Goldberg, set to the famous keyboard variations, he asked the pianist to play every repeat in the music, at an unnaturally slow speed. The resulting dance is long enough to tire even the most enthusiastic viewer. The pieces were composed by Bach as a way to fill his patron’s sleepless nights; perhaps it is appropriate that several audience-members napped during its performance. And yet, it is an extraordinary ballet, full of ideas and references to other ballets and styles of dance.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

From the New York minimalists who were making work around the same time, Robbins got the idea to explore the simplest pedestrian movements, like walking, sitting, turning. His love of Balanchine is expressed in quotations from Agon, Concerto Barocco, and Square Dance. His interest in the dynamics of partnering inspire quietly ingenious duets for men and women, men and men, and women and women. There is a long quartet in which the dancers trade steps; you get to see a step executed first on pointe by two women, then in soft slippers by two men. And a section devoted almost exclusively to a movement that looks like a Falstaffian belly laugh. This profusion of variations is placed within a gorgeous, gilded frame: an introduction and coda in which two beautiful dancers, Miriam Miller and Aaron Sanz, move in simple, decorative steps reminiscent of baroque dance. Despite its longueurs, Goldberg is a work rich in imagination, sensitivity, and restraint, in which the dancers look radiantly themselves.

In contrast, Les Noces comes across as an unconvincing fantasy, a Russian folk-ballet imagined by a mid-twentieth-century New Yorker. He actually made for a different company, American Ballet Theatre, more suited to such theatrical, earthy stuff. Despite moments of stylistic ingenuity, Robbins’ interpretation of Stravinsky’s crushing and savage score – a cantata depicting oppressive rituals of marriage in a hyper-traditional, archaic world – never reaches maximum impact. In contrast, Bronislava Nijinska’s 1923 version is like a life-devouring machine. At least Robbins had the good sense to place the orchestra – four pianos, percussion, choir, and soloists – onstage. Still, I found the two protagonists, doe-eyed Andres Zuniga (an apprentice) and a blank, almost puppet-like Indiana Woodward, moving. Again and again, the group thrusts them into each other’s arms. Sean Suozzi, one of two “matchmakers,” also stood out, attacking the steps with a wildness that came close to capturing the fervor of the music.

Robbins was as much a master of the Broadway stage as he was a man of the ballet. Sadly the medley crafted by Warren Carlyle out of musical-theater pieces like The King and I, Fiddler on the Roof, and On the Town is more of a costume parade than a showcase for Robbins’ theatrical savvy. The singer, Jessica Vosk, didn’t help matters with her strident, insincere delivery. The choreography is watered down, chopped up, and clumsily sewn together like one of those glitzy mélanges at the Oscars. You sense instantly that this concoction of bits and pieces isn’t built to last. And also that Robbins would not be happy to see it.

On the other hand, Circus Polka, for 48 students from the company school, is a charmer. The clever twist is that the kids keep getting smaller, rather than the other way around. At the end, the girls arrange themselves in the initials J.R. – originally it was I.S., for Stravinsky, who composed the score. Robbins certainly knew how to entertain.

One of the things that has changed at the company since the departure of Peter Martins is that it has begun to bring in the originators of various roles to coach dancers. What good fortune for Joaquín de Luz, who is retiring next season, to have Baryshnikov in the studio to give him pointers on A Suite of Dances. (Baryshnikov also coached Other Dances.) One could sense Misha’s touch in the humor and almost Twyla Tharp-like irony of some of the steps. But De Luz also brought to it his own straight-forward and sunny personality. The dancer and cellist are alone onstage. He listens, and, seemingly spontaneously, tries out a few steps. As in Goldberg, many of the movements are un-spectacular: walking, swiveling hips, bobbing to the beat, moving a hand or an arm. It’s not major Robbins, but it conveys a mood. And creates a sense of intimacy.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

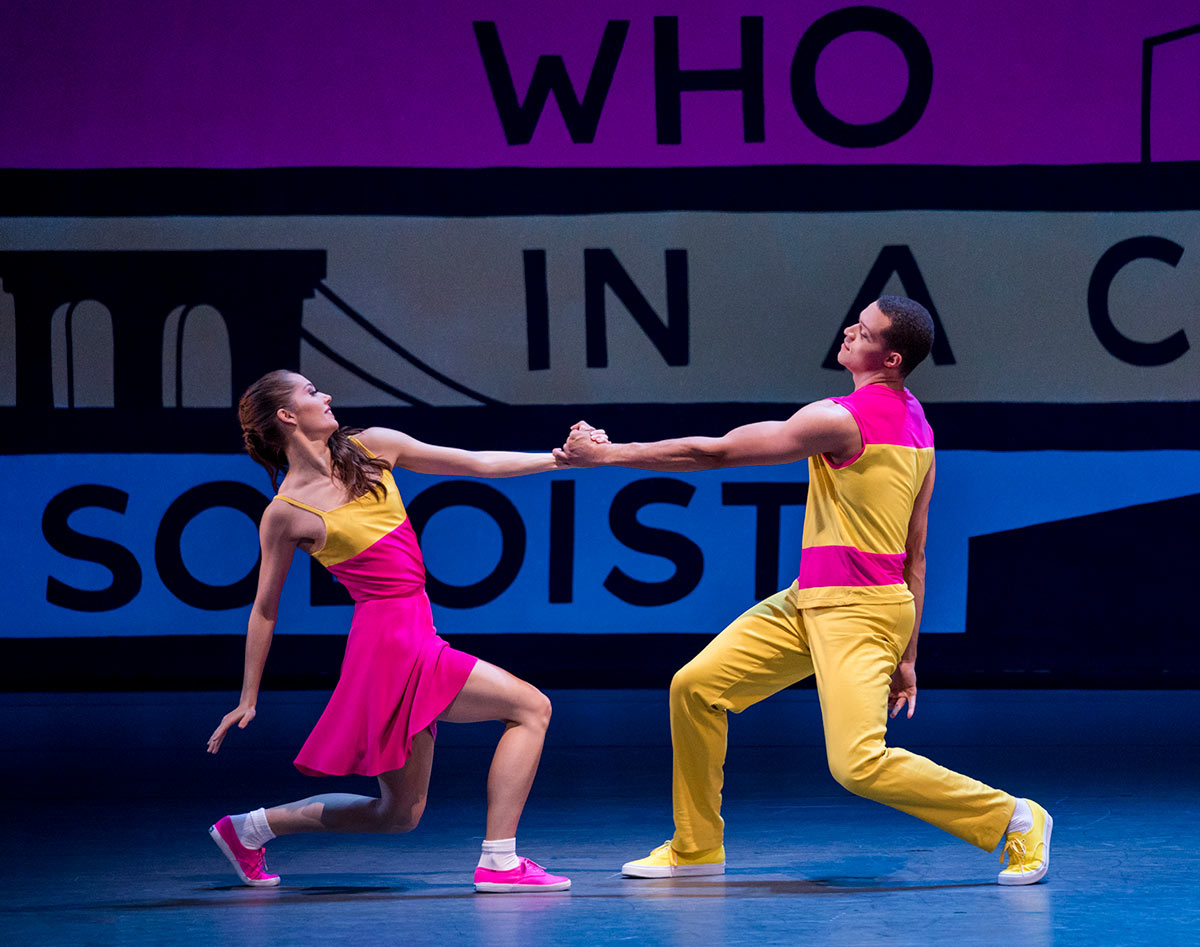

Justin Peck’s tribute to Robbins, Easy, may not be major Peck, either, but it is certainly a pleasing piece of jazzy movement. Starting with The Times are Racing, Peck has been exploring a new vocabulary, a mix of tap and jazz and sped-up ballet, often in sneakers. The partnering is quick and unsentimental, full of kicks and flip-lifts and changes of direction, like a sped up lindy-hop. The arms move at lightning speed, then slow down, or the other way around. The feeling is syncopated, fidgety, bright. Easy is the brightest of these, tricked out in day-glo colors by Stephen Powers, echoed by the sporty costumes (by Reid Bartelme and Harriet Jung) and the lighting (by Brandon Stirling Baker). Six dancers, led by an energetic Harrison Coll, jostle for attention, switching partners and personas. The music, by Leonard Bernstein (his Prelude, Fugue and Riffs) is jazzy and hot. Easy is brief, but assured, full of style.

One can see clearly what Peck has learned from Robbins, and where he goes his own way. It’s hard to imagine Peck creating something like Other Dances. Warmth and simplicity are not really his thing. Maybe it’s a question of maturity, or maybe we’re just living in a different time. But Robbins still has a lot to teach, and a lot to give.

You must be logged in to post a comment.